Sept 8 - Nov 5, 2021

Essay | Installation Views | Artist Statement

For pricing and availabilty, please contact the gallery at 212-581-1657

Installation Views

Essay by Emily Lenz

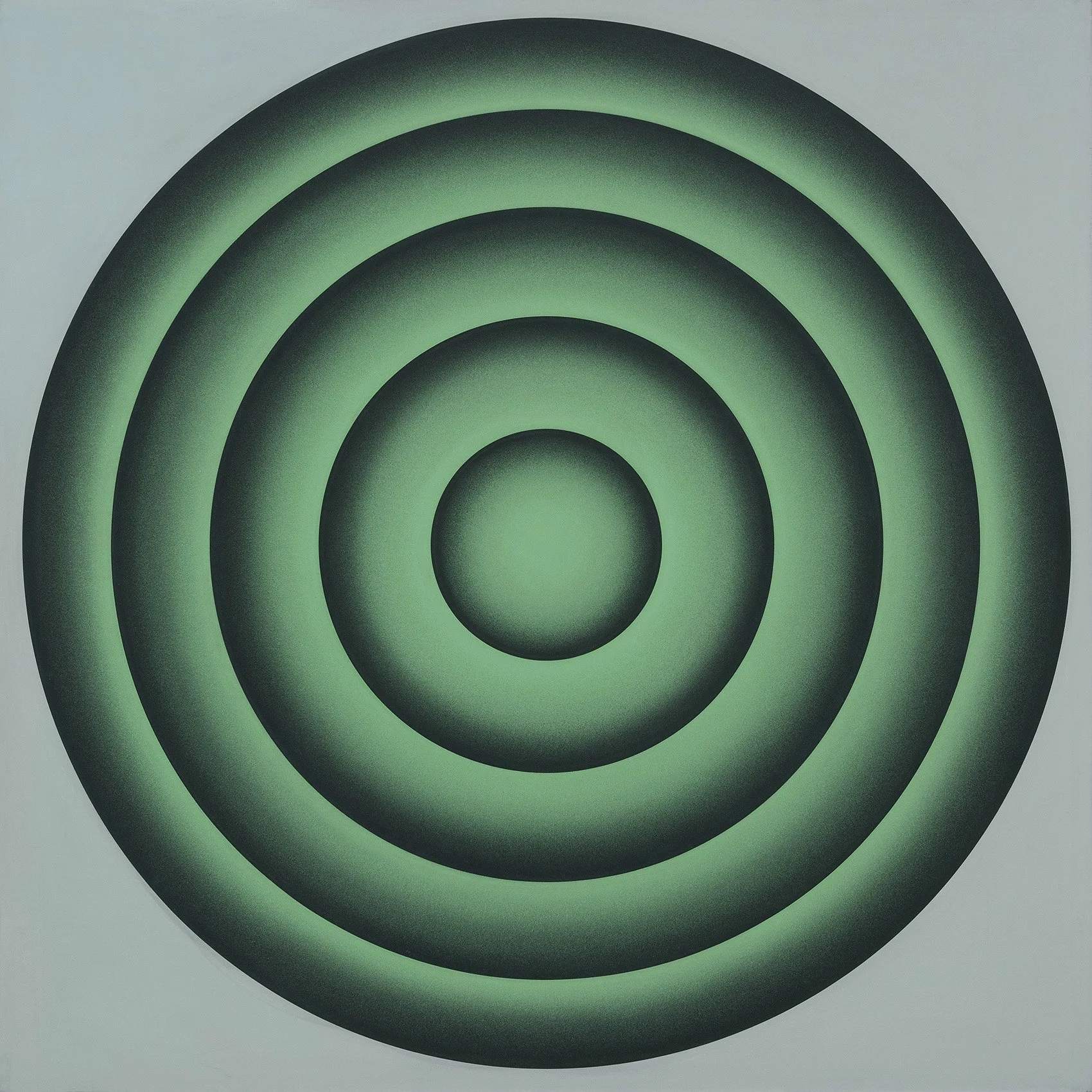

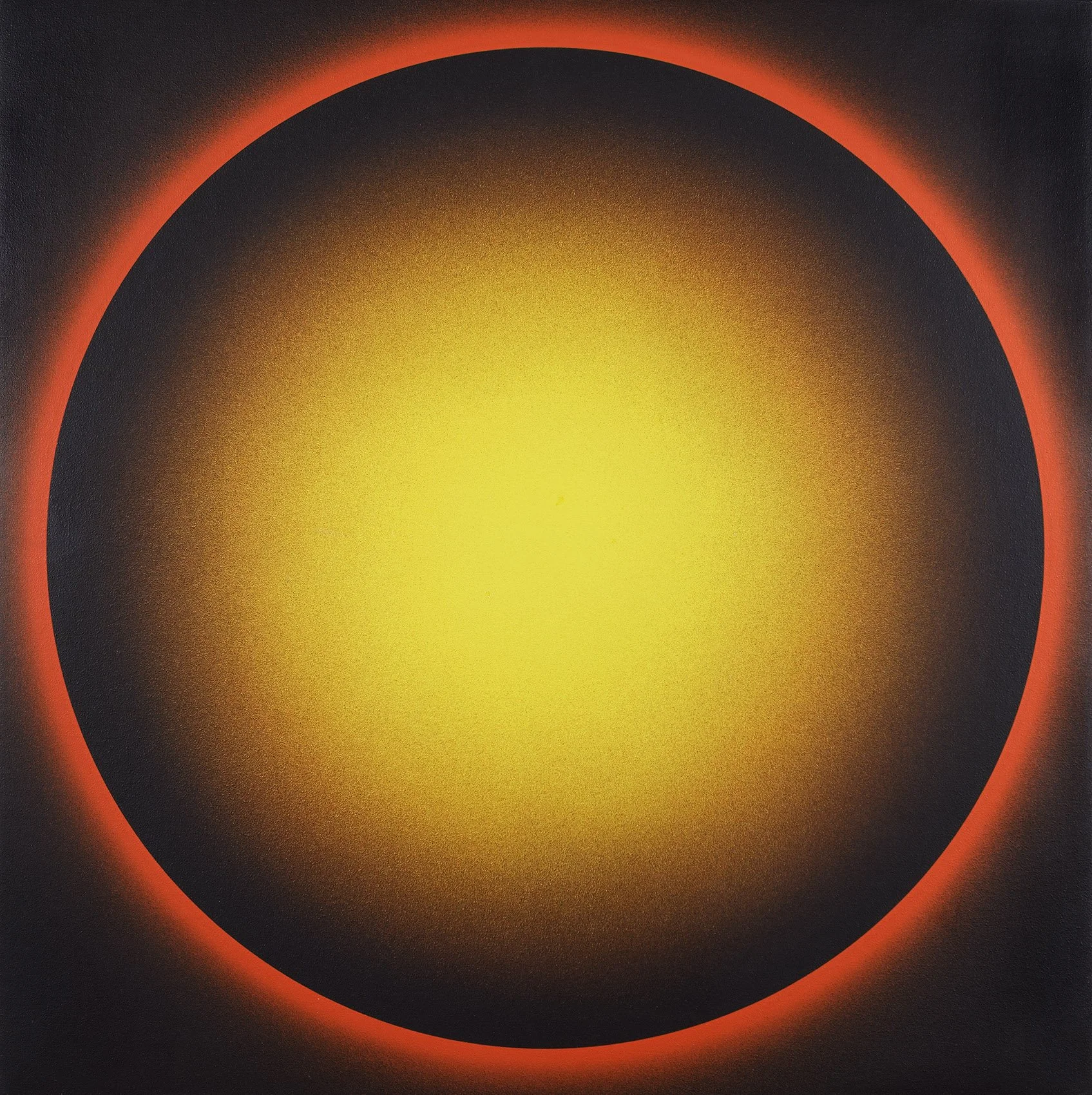

Our exhibition focuses on the years 1964 to 1970 when Tadasky (Tadasuke Kuwayama, b.1935) developed his distinct style and was exhibited widely in New York with Sam Kootz and Fischbach galleries and in Japan with the Tokyo Gallery and the Gutai. In the 1960s Tadasky’s paintings went from bright targets and flat spinning discs in the A, B, and C series to pulsating rings in the D series to glowing orbs in the E and F series. Tadasky numbers rather than titles his works as he wants them to be universal and timeless.

Tadasky painted about 100 paintings before showing his work to anybody. In 1964 Ivan Karp was one of the first to view Tadasky’s work and he spread the word to Leo Castelli and the Museum of Modern Art. The more aggressive dealer Sam Kootz visited the studio, purchased paintings, and offered Tadasky a solo exhibition. Tadasky accepted, pleased to have the same New York dealer as Picasso. Over the next two years until Kootz’s retirement in 1966, he sold over 80 of Tadasky’s paintings to many important collectors, including Larry Aldrich, David Rockefeller, Frederic Weisman, and James Michener.

Tadasky’s work was identified as Op art when curator William Seitz included him in the Museum of Modern Art’s 1965 exhibition The Responsive Eye of international Op art. Tadasky’s work demonstrates Op’s characteristic openness to viewer interaction. With an investigative approach in their studios, Tadasky and his peers including Richard Anuszkiewicz (1930-2020) and Julian Stanczak (1928-2017) applied new understandings of perception to create a new model of depicting space. These artists explored the relationship of color and line to achieve movement that projects and recedes. The viewer’s participation in an active visual dialogue was fundamental to the work; the ultimate goal was to create a heightened awareness of what it means to see and a new way to evoke nature’s energy.

Arriving in New York from Japan in 1961, Tadasky developed his distinctive technique to create precise concentric rings of vibrant color. Inspired by the potter’s wheel, he built a turntable easel that rotated the canvas beneath him. Using traditional Japanese calligraphy brushes, Tadasky painted thin lines that build up to the broader rings we see in the paintings. This requires deep focus as he carefully calibrated the paint flow onto the undulating surface of the rotating canvas. In the 1960s Tadasky used 10 colors – first making his own paint by mixing pigments into newly available acrylic emulsions then moving to commercially made tubes when success permitted the expense.

In the A series, Tadasky applies rings of raw color using their proximity to create optical blending. In both B-181, 1964 and C-162, 1965, Tadasky repeats a four-color pattern. The equal width and vibrancy of the colors intensify the color interaction, causing a spinning and flickering effect. While the works are very active, they are also flat. A new element of dimension occurs in our exhibition with C-200, 1965 marking a pivot point. Red, blue, and yellow are arranged without pattern in varying widths divided by spaces of white that allow the colors to breathe. The painting can read as either spinning flat or pulsing in and out, a new element of dimension.

In the second half of the Sixties, Tadasky explored how his paintings could create expansive vision regardless of size. As Tadasky said, I work with a limited space – the surface of the canvas. Yet I can create depth, through which you can enter the painting. The works from this period are ethereal and bold. One can see this transformation comparing D-109, 1966 and D-212, 1970. In D-109 the gradation of color from yellow at its center to red at the edge produces a luminous heat. Drawn out of a black background, the color increases in vibrancy at the center when the black circles thin out producing a radiant effect. Tadasky uses black in a new way in D-212, applying it with an airbrush to the edge of each ring, achieving a new level of volume in the buoyant pile of inner-tubes.

While painting the late D series, Tadasky noticed the occasional blobs of paint on the canvas when his airbrush got backed up and realized he could slowly build up a textured surface by using his airbrush at low pressure. The result was the E series in which Tadasky develops great depth with floating spheres and atmospheric ground. While predominantly monochrome, the E series has shimmers of different colors achieved by spraying paint in a single direction, as seen in the umber halo in E-119, 1969 created by a light spray of red across the blue crags of the ground layer.

For Tadasky, the square format of his paintings allows each one to be a transformative space. The circle-in-the-square format parallels the clarity and symmetry Tadasky feels upon entering a Shinto shrine. Each painting is its own world and Tadasky strives to make it all-encompassing.

Artist Statement

I use the circle to create my own world, a world that no one has seen before, my own universe. The closest comparison for me is the experience of entering a traditional Shinto shrine: because they are both so simple and symmetrical, the impact is very powerful.

The circle is of course something from nature. But I have no desire to depict nature; rather, I want to reproduce that power, that “vibration” that we experience in viewing nature’s beauty.

If a painting is good, it explains itself, it lasts. My paintings are not meant to refer to anything, and there is no philosophy or theory involved. People are free to look at my work in many different ways.

Color helps to create depth. I work with a limited space—the surface of the canvas. Yet I can create depth, through which you can enter the painting.

I love trying new ideas and approaches. But at the same time, each work evolves from the one before. I have learned that when you polish something over and over, it shines in its own way.

I spend a lot of time thinking before I paint. I wait until an idea is very clear in my mind. When I begin to paint, I know precisely what colors I will use, what width of line, what shapes. I don’t change anything once I begin to paint. To change the idea along the way is “taboo” for me.

It is always wonderfully exciting to see the painting complete. Indeed the entire process is full of joy – if I didn’t enjoy painting, the result would never be good.

-Tadasky, 2015

[ TOP ]

Modernism 1913-1950 | Realism of the 1930s and 1940s | Abstraction of the 1930s and 1940s | Post-War | Selected Biographies