May 8 - Aug 31, 2018

at 499 Park Avenue

Jan 27 - Aug 31, 2018

Essay | Geoform Interview | Selected Work | For availability, contact gallery at 212-581-1657.

Essay by Thomas Micchelli

Tadasky (Tadasuke Kuwayama, b. 1935, Nagoya, Japan) came to the United States in 1961, intoxicated with the possibilities of abstraction — especially the geometric rigor of Homage to the Square, the series of paintings by Josef Albers that formed the foundation of postwar color theory.

Over a career spanning nearly six decades, Tadasky has devoted his practice to the geometric motif of the circle, through which he has pursued his two preoccupations: the interaction of color and an incomparable control of the brush.

There is no trial-and-error in Tadasky’s approach. Each new painting springs fully formed from his imagination while he is at work on the previous one — a meditative process that is both deeply felt and serenely impersonal. This is why Tadasky titles his paintings with letters and numbers — a letter denoting the series, and a number identifying the location of the work within the sequence — there are no references to the world outside the frame.

The superhuman perfection of Tadasky’s concentric circles is founded on the specialized human qualities of discipline and skill. They are made on a large turntable of his own devising, which is overlaid by a wide plank (an expert woodworker, his family’s business had been the manufacture of impeccably crafted Shinto shrines).

Sitting cross-legged on the plank, he rotates the turntable with one hand while lowering the tip of a paint-soaked brush to the canvas with the other, gripping it with a firmness that must be at once rock-solid and highly attuned to the minute variations of the fabric’s warp and woof.

Look carefully at the lines constructing the concentric circles, and it soon becomes evident that what greets the eye with the exactitude of an inkjet is in fact a brushstroke animated by infinitesimal degrees of expansion and contraction, like the breathing of a snake.

The variations on the circle that Tadasky has explored over the course of his career range from vaporized spatters to compacted matter to rings of fire. Each series encompasses a coherent visual statement, such as the solid ball floating like a cold sun in the E series, or the expressionistic brushwork that forms the ragged circumferences of the G series.

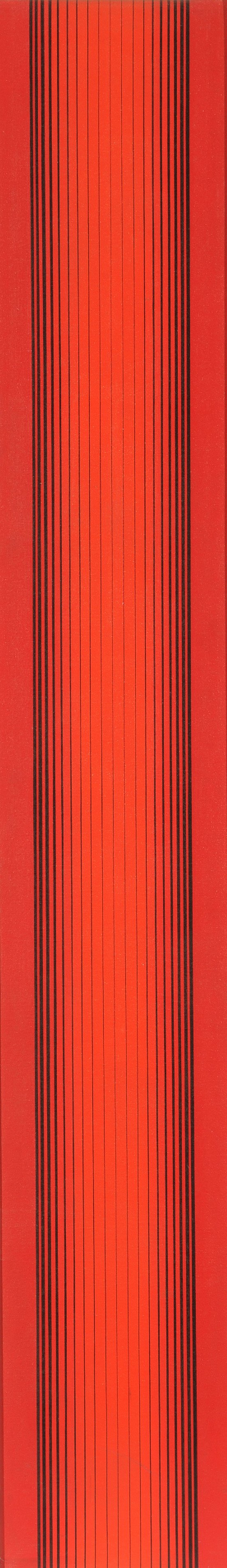

The works in this exhibition have been selected from series D, completed more than fifty years ago, between 1966 and 1967. Coming only a few years after Tadasky committed himself to circles, the D series includes striking departures from the artist’s customary format of a circle enclosed within a square canvas. In D-155 (1966-67) and D-156A (1966), severely cropped circular bands interlock and overlap, disrupting the calm embodied by their neighboring concentric compositions. Further, Tadasky extracts the bands of color into narrow, vertical single-stripe paintings, which are created through an equally meditative process involving a large, rotating drum.

At the time Tadasky was making these paintings, critical attention was split between an austere Minimalist/Conceptualist aesthetic and its antithesis, Pop. In brief, Minimalism focused on the artwork’s material composition and its status as an independent, non-referential object, while Conceptualism contended that the object was subordinate to the idea behind it. Pop Art, in contrast, drew its influences from mass media and popular entertainment, including advertising, graphic design, and comic books.

Other approaches, however, arose in tandem with the mainstream. One was Perceptual Painting, dubbed Op Art in the popular press, in which pure abstraction is channeled into high-key, optically vibrating surfaces. (This movement was codified in The Responsive Eye, an exhibition organized in 1965 by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which prominently featured Tadasky’s work).

Tadasky’s D series incorporates aspects of each style without allowing a single current to dominate. The elemental motifs of circles and stripes reflect the Minimalists’ formal rigor, while the artist’s insistence that his paintings reference nothing beyond themselves aligns with their advocacy of art’s self-possession. The exacting internal consistency of Tadasky’s various series and the preconceived mental image that governs his painting process imply a Conceptual context for each work.

Perceptual Painting is manifest in the alternating patterns of thick-to-thin black lines, which set off an optical surface buzz while demarcating tightly packed, convincingly rendered cylindrical volumes. And the solid bands of blue, red, yellow, orange, and violet recall the luminous tones of printer’s ink in both comic books and Ukiyo-e prints, the popular Japanese graphic art form practiced from the 17th to the 19th century. It can be argued that, with Tadasky’s D series, the look and feel of Ukiyo-e, which influenced American comics and, in turn, Pop Art, have come full circle in the abstractions of a Japanese-American painter.

Reading into the possible influences on Tadasky’s paintings can be a reward in itself, but background knowledge is not necessary to understand his work as he intends it — a visual portal into a perfect realm of abstract color, shape, and line.

[ TOP ]

Modernism 1913-1950 | Realism of the 1930s and 1940s | Abstraction of the 1930s and 1940s | Post-War | Selected Biographies