May 8 - Aug 31, 2018

Essay | For inquiries, please contact the gallery at 212-581-1657.

Essay by Deedee Wigmore

The agricultural landscape and the people whose labor made it productive are central to this exhibition. The farm had an historic place in the American imagination. It stood for the values of self-reliance, industriousness, and public spirit. It was a world of plenty resulting from laborious repetitive work. When Europe was at war from 1914-1918 the USA became the breadbasket of the world, but as Europe recovered from World War I commodity prices fell, and farmers who had borrowed for new machinery or to buy land struggled. Between 1920 and 1929 nearly 6 million people left farms and rural bank failures reached record levels. The Depression for farmers occurred between 1919 and 1932 when their net income fell 70% and the Plains States were afflicted with the Dust Bowl caused by poor land use practices coupled with wind and drought. Relief for the Plains States and the Midwest farmers came with New Deal policies starting in 1933 and as Europe moved toward World War II late in the decade.

Farm recovery came with President Roosevelt’s New Deal. He devalued the dollar 65%, raising commodities prices, and instituted numerous farm programs such as the Agricultural Adjustment Administration and rural electrification. Four government projects were dedicated to supporting the arts: the Public Works of Art Project (1933-34), the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (need-based support of a variety of artists, 1935-1943), the Section of Fine Arts in the Treasury Department (commissioned murals won by competition, 1934-1943), and the Treasury Relief Art Project (need-based hiring for decoration of Federal buildings, 1935-38). The American Scene dominated in these projects because it spoke to a wide audience with its representational style and commonplace subjects connected to regional history, geography, and culture. The American Scene artists aimed to record rural America and preserve its integrity as a vital part of society. To preserve knowledge of American farm life, artists documented the farmer’s landscape, work, stock, and specific crops harvested. The Midwest was a natural cradle for this kind of American Scene art as many of its artists came from farms and farming communities then went to art schools in Cleveland, Kansas City, Chicago, Minneapolis, and St. Paul.

American Scene artists gathered from many art styles to create a new American realism that dominated the 1930s and 1940s. Some ingredients in the American Scene style can be traced back to The Armory Show of 1913, which created a state of uninhibited art exploration offered by European innovation. These international styles, of which Cubism and Expressionism are most represented, along with the Hudson River School, folk art, and Precisionism were assimilated to create a new American narrative. This can be seen in the farm subjects selected for our exhibition that demonstrate the mixing of European and American styles for a modern effect.

Beginning at the turn of the century, European modern artists considered various kinds of folk art to break from the formality of classical painting. By the early 1930s interest in folk and vernacular art began to develop in America and the art establishment came to accept it as art. This was reflected in folk art exhibitions at The Newark Museum in 1932 and New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1933. In our exhibition, the American farm as depicted by Ben Shahn’s (1898-1969) Harvesting Wheat (1940) has a shallow perspective that is sophisticated and derived from Cubism, while the figure of the farmer and the harvest elements have the simplicity of folk art. They convey the narrative of muscle and heavy work done by a simple, honest man. In Corn, Hay, and Rye, 1946, Georgina Klitgaard (1893-1976) saw the harvest landscape as a flat all-over pattern which she composed like a stage set with vines framing the top and bottom. Petra Cabot’s (1907-2006) The Hog Pen, c.1940 contrasts a close up view of a rustic hog pen against a highly edited background of a pink barn. The unexpected combination gives the painting the charm and whimsy of folk art.

Cubism, like folk art, was also used by American Scene artists in traditional subjects. The original Cubists were looking for the geometric forms underlying nature and abandoned deep space perspective to achieve a more compact composition in which foreground and background are fused. Field Workers, 1930 by Peppino Mangravite (1896-1978) and The Farm at Evening, c. 1930 by Jan Matulka (1890-1972) each use a Cubist perspective and its neutral dark palette.

The fundamentally geometric shapes of farm buildings lent themselves to the American Precisionist style developed in the 1920s. Precisionism, like early Cubism, simplified forms and suppressed details. Both styles were a compromise between abstraction and realism. In Precisionist paintings the abstract quality was never lost due to the style’s severe simplification of planes and volumes to emphasize architectural and industrial forms. Impact was achieved through editing details of a scene, leaving only those which created a feeling of strong rhythm and pace. Use of photography by Precisionist artists led to new treatment of light that could either be clarifying or mysterious. With the development of the inexpensive handheld camera in 1930, American Scene artists began to use photography to create paintings with unusual angles, perspectives, and lighting. Precisionist compositions of flattened forms and silhouetted structures with sharp edges are easily recognized. Using photography and the Precisionist interest in architectural forms, this allowed artists to both romanticize the pioneer days and create a more modern effect in their farm subjects.

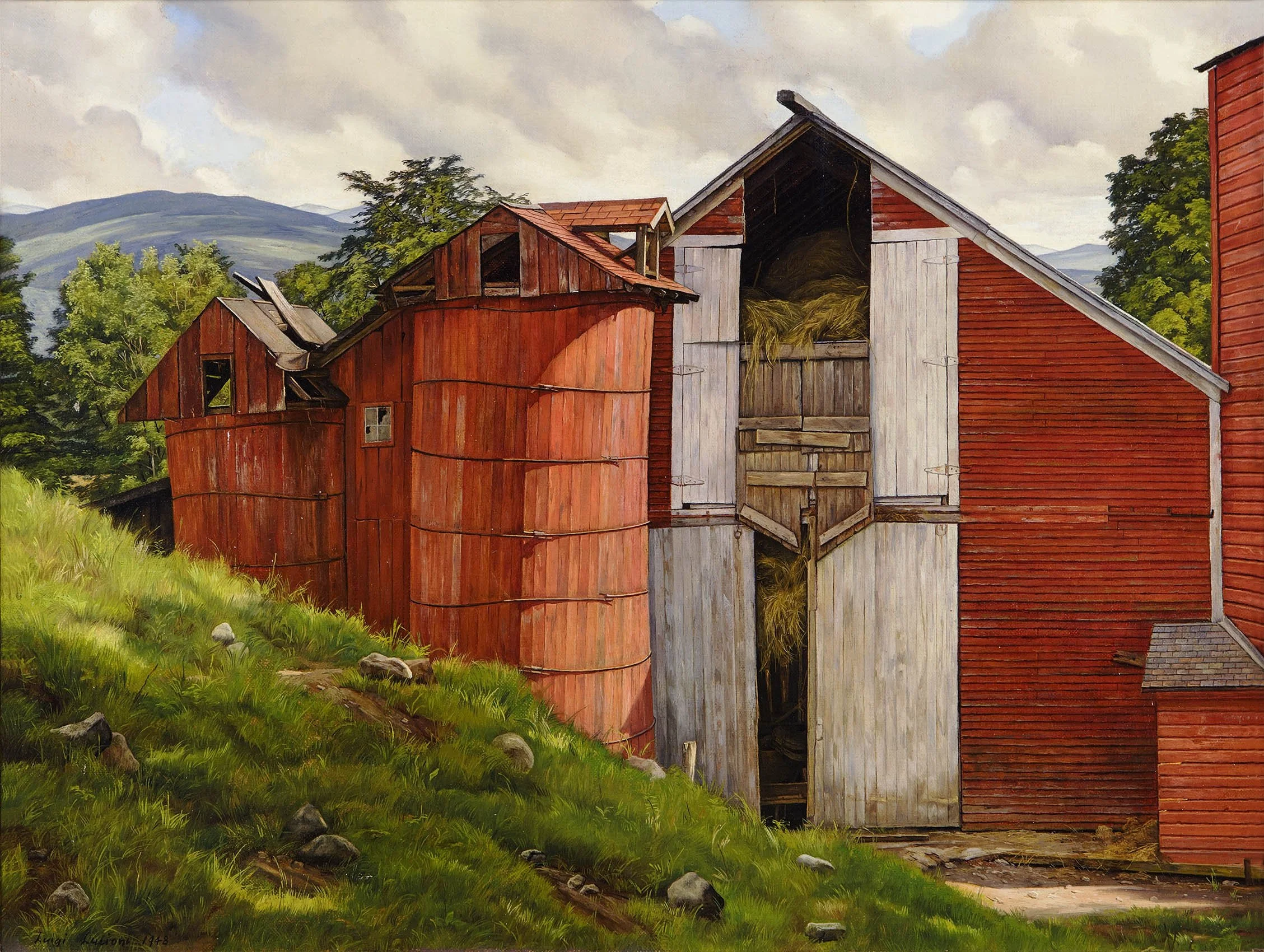

We see the architectural focus coupled with different photo-like perspectives in three paintings—close up in Ernest Fiene’s (1894-1965) Lasher Farm in Winter (1926), the middle view in Paul Sample’s (1896-1974) Vermont Farm, 1937 and a distant view in Peter Hurd’s (1904-1984) Rancho del Charco Largo, 1939. The lighting in Ernest Fiene’s Lasher Farm is winter’s flat gray. Farm buildings keep the focus in the foreground where there is rhythmic retention of detail in the fields. Paul Sample’s Vermont Farm has the light of midday. Two elements in the painting keep the viewer’s eye in the midground- the white barn and the shadows under the cows. Peter Hurd’s distant silhouettes of Rancho del Charco Largo against an evening sky strengthens the viewer’s feeling of an open, endless, dry farmscape. The role of photography is more obvious in the work of Luigi Lucioni (1900-1988) in such paintings as Barns on the Road, 1948 and Nestled Barns, 1948. Because Lucioni saw the great barns as monuments to labor threatened by economic conditions, he painted them close up with precise detail in different lights.

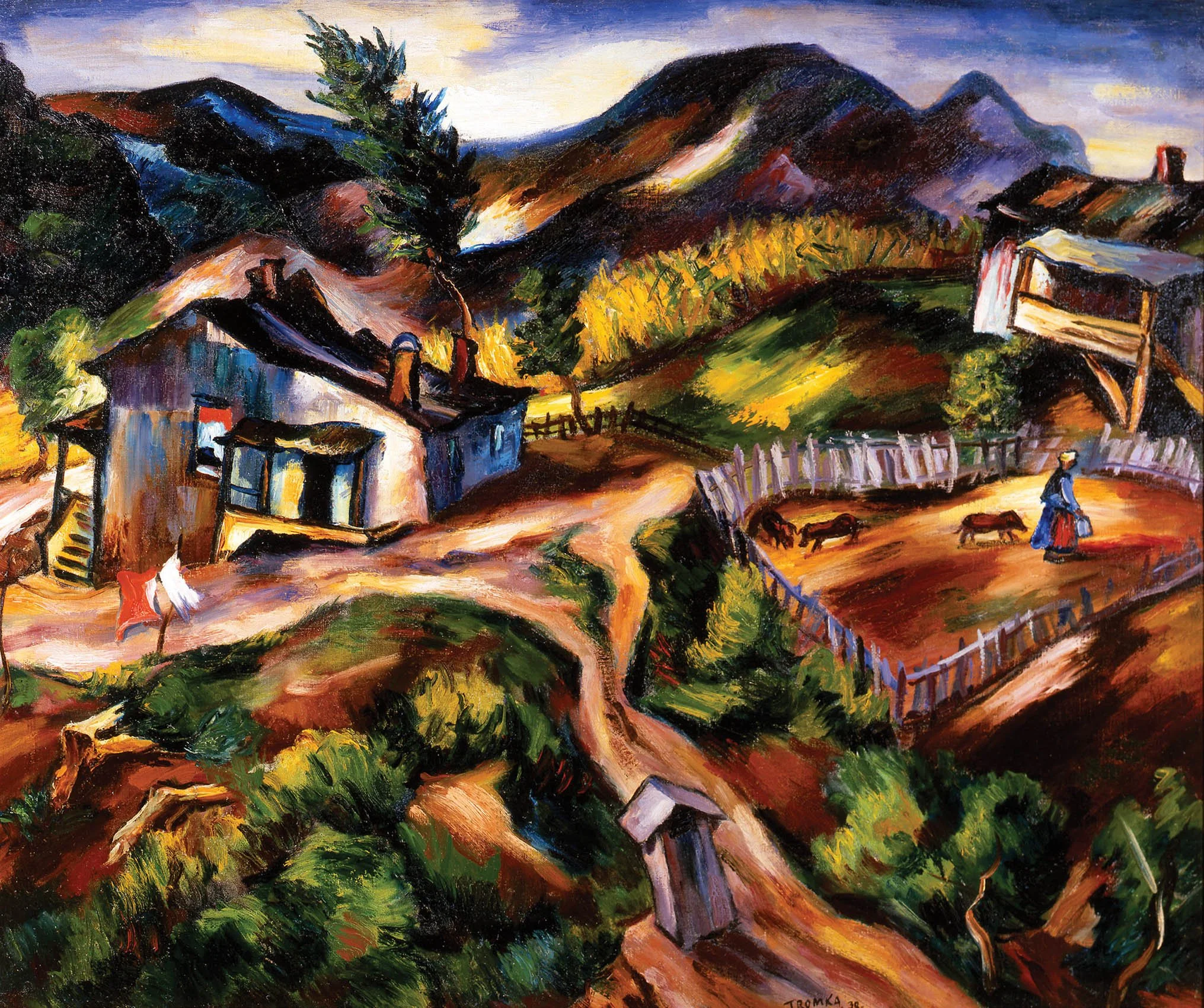

Some American Scene artists found the Expressionist style offered a means to render visible their complex feelings towards a place. They felt photography lacked emotion and edited out geographic specificity. In a realist style, character and feelings could be expressed through gesture and attitude. However, by adding elements adapted from Expressionism, greater impact could be achieved in portraying both economic and social problems. While pure abstraction did not allow easy discussion of problems, the use of Expressionist intense arbitrary color, textural surfaces, and startling distortions of form add punch to social comment. A painting by Abram Tromka (1896-1954) titled Old Kentucky, 1938 uses this kind of acidic color and texture to speak of the hardship of farm life. The Expressionist tendency to exaggerate types of humanity allowed for satirical use as well. A painting open to interpretation is Clarence Carter’s (1904-2000) Jane Reed and Dora Hunt, 1943. Carter uses aspects of Expressionism to emphasize the pluck of two very thin farm women picking up coal chunks on the railroad tracks for fuel. Their bonnets either suggest the women have been marooned in time or comment on their isolation and poverty.

Critics describing the American Scene style as too direct or simple do not consider the feat American artists achieved in developing a recognizable style out of an amalgam of ideas derived from the Cubists and Expressionists, which offered modern stylistic elements such as distortion, irregular perspective, exaggerated or reduced spatial depth, and elongated figures. American Scene artists added from their own history Precisionist compositional ideas that discarded excess detail, generalized characters, and used photography to modernize compositions and tell the story of America facing the changes brought by industrialization, immigration, depression, and world war. The Depression of the 1930s and W.P.A. programs created new social relationships, basic changes in the social function of art, and new aesthetic concepts. Responsibility of the individual and freedom were not abstract ideas in the 1930s-1940s. American Scene art was a new national style, the product of America dreaming of a democratic art.

[ TOP ]

Modernism 1913-1950 | Realism of the 1930s and 1940s | Abstraction of the 1930s and 1940s | Post-War | Selected Biographies