October 19, 2020 - February 15, 2021

Essay | Installation views | For availability and pricing, contact the gallery at 212-581-1657

Installation Views

Essay by Deedee Wigmore

The reopening of the Whitney Museum and its exhibition Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945 provides a picture of the purpose art has served in troubled times and made me wonder how the Mexican muralists, who were all revolutionary, helped America reimagine itself during the Great Depression. To examine that question, one needs to know why Americans were receptive to the Mexican muralists.

After the stock market crash on October 29, 1929, economic problems worsened into a global depression. As Americans lost jobs, homes, and savings, tensions were accentuated between: immigrant ethnic groups; farm and town dwellers; physical and mental occupations; and progressive politics and conservative traditions. The Depression threatened American utopian notions of opportunity and progress. Racial violence flared in the 1930s because of economic competition. Violence caused protesters to raise questions about social justice and the American legal system. Bitter economic hardship led some to regard democracy as an ineffective form of government.

The Mexican mural program of the 1920s was part of rebuilding the country after ten years of brutal class warfare. The mural program depicted the life of everyday Mexicans as a means of connecting the people to their new government. The American artist George Biddle had traveled in Mexico in 1928 and been a house guest of Diego Rivera. He saw the impact of the Mexican government-supported public art program for both the artists and the people.

In 1933 George Biddle proposed a public works project for the arts to newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt in a personal letter. Roosevelt liked the idea that artists could rally a fractured society around social ideals. The first American public arts program began in 1933-1934. Roosevelt expanded the arts program to include archiving American design, historic preservation, and teaching community art classes as part of the Works Progress Administration. The WPA also built dams, roads, parks, electrification, and other infrastructure from 1935 to 1943, employing 8.5 million as part of the New Deal.

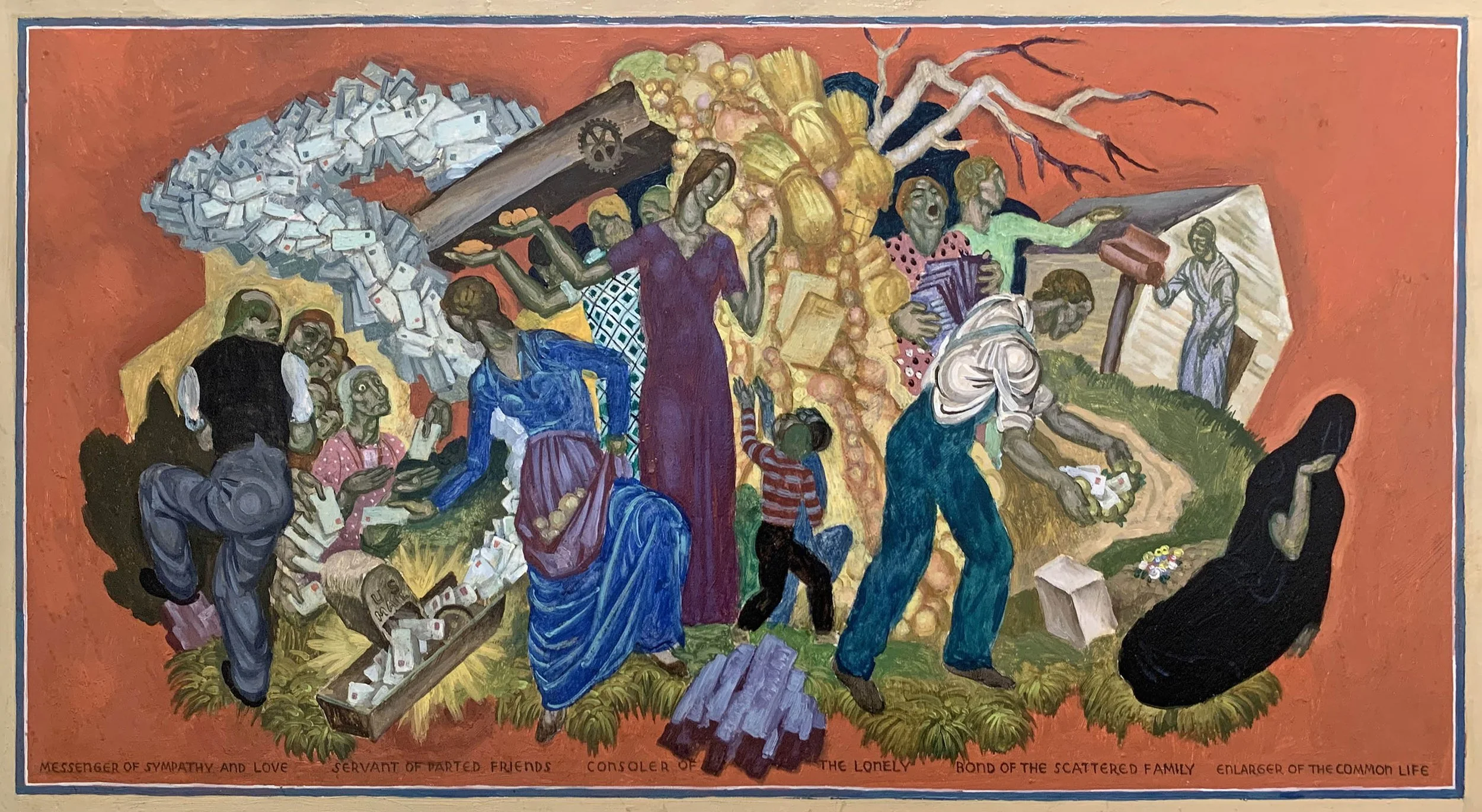

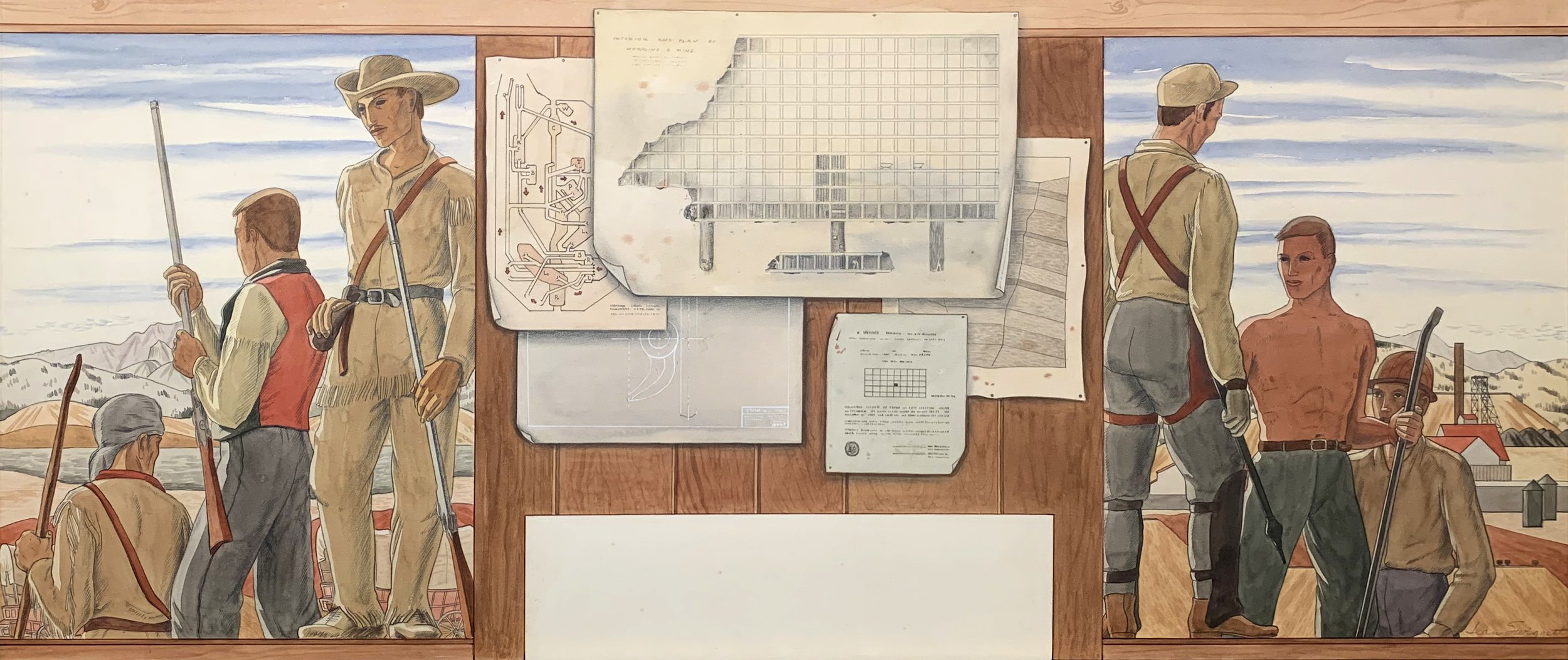

The American public art programs, like its Mexican counterpart, elevated to wage earners artists who created murals, easel paintings, prints, and sculptures. The Section of Fine Arts from 1934-1943 awarded commissions for art installed in public buildings, particularly post offices. The Treasury Relief Art Project awarded commissions from 1935-1939 for new and existing federal buildings. For every mural commission granted, a great many artists submitted an oil, watercolor, gouache, or drawing of their interpretation of a specific theme or location. Thus in organizing an exhibition at my gallery to consider the contribution of the Mexican mural program to America, I offer nine mural proposals to view.

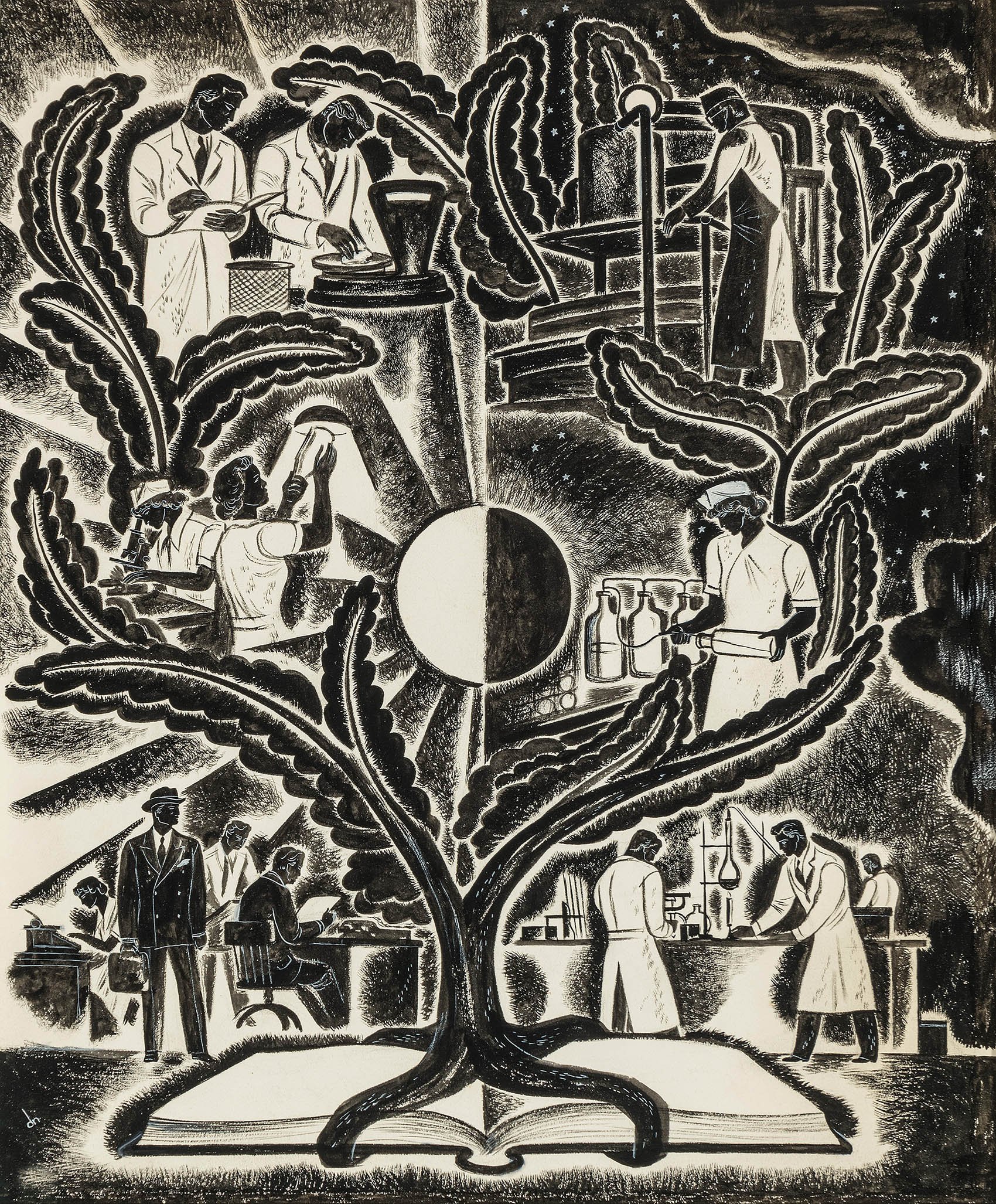

The Mexican artists focused on murals because they were monumental, public, and owned by the people. Easel painting was repudiated in Mexico as private intellectual art. The American mural program valued both mural and easel paintings, which allows me to provide a good comparison of the subject matter of easel paintings to go with the mural studies in my gallery exhibition.

The Mexican muralists became known to American artists through: travel to Mexico during the 1920s; their murals painted in America; museum exhibitions; and more broadly through the press and printed material from 1930-1940. The idea of unifying a country through art celebrating national traditions, history, and the everyday life of ordinary people was taken from the Mexican mural program. More importantly, the Mexican muralist style gave new vitality to representational art at a time when abstraction and non-objective art was heralded as progressive and synonymous with individual freedom. It settled the question of which style- realism or modernist abstraction- would best express the American story. Government programs in both Mexico and the United States chose realism over abstraction for most of its commissions as realism was considered more accessible to the public.

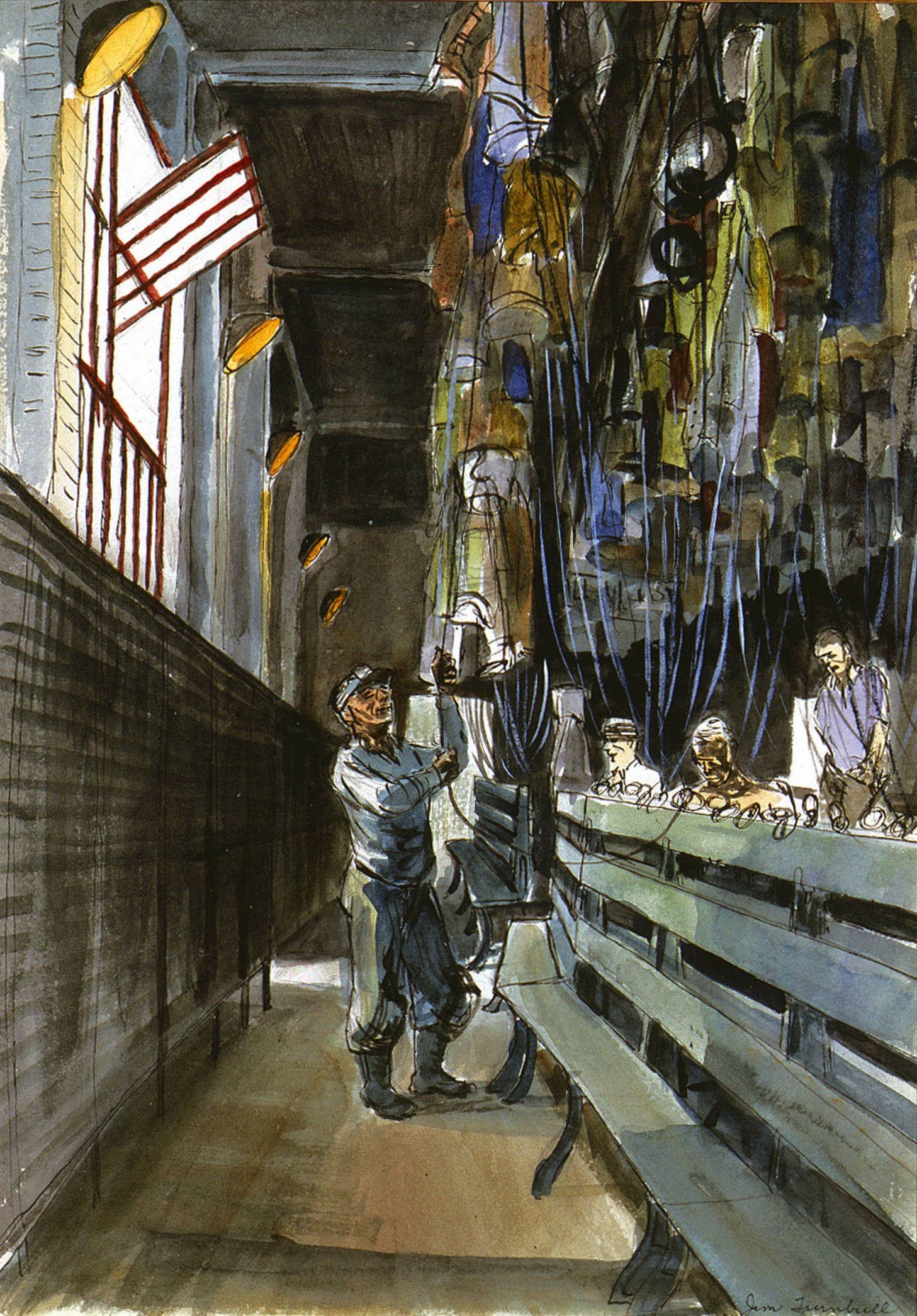

American realist artists were made up of Social Realists and Regionalists. The Social Realists presented an argument for organized workers erasing economic inequality. They are best represented in our exhibition by Ben Shahn’s welder in You’re Stronger than Steel and Joseph Lomoff’s miner in Toilers of the Underground. Paintings in our exhibition of train cars by Charles Burchfield and Reginald Marsh, on the other hand, celebrate industry by emphasizing streamlined machinery as an expression of American power. Jan Matulka in Up and Up uses structural design to depict industry as ordered and pristine. His streamlining of shapes suggests American efficiency. For their subjects, Regionalists focused on community in rural towns, farming, regional topography, and great moments in their state or local history. The Regionalists aimed to give people heart and pride by recalling their skill as farmers and ranchers. Like the Mexican muralists, the Regionalists tell the story of man’s heroic struggle with his environment and his will to live. Our exhibition has Regionalist works such as Joe Jones’s Farmer with a Load of Wheat and Adolf Dehn’s Colorado Mining Town. Whether Social Realists or Regionalists, American artists did not erase race or poverty from their narratives. We have on view Albert Gold’s painting of a black worker in Fish Packing and Joe Jones’s Eskimo Caulking Boat in our exhibition. Their murals and paintings tell an inclusive story.

American artists adapted style elements they liked from the Mexican muralists, especially high key color and stylized juxtapositions of montage storytelling. Regardless of their aesthetic interests, political affiliations, and choice of locations painted, artists in the United States all felt pressed to negotiate a way between the national identity claimed by the Realists and Modernism’s connection to European abstraction. Cubism and Surrealism were adapted to allow free association and juxtaposing of pictorial motifs for new ways of storytelling. Both Eugene Savage in his mural proposal for the Post Office Building in Washington, DC and Aaron Bohrod in his mural proposal for the Vandalia Post Office in Illinois are examples of montage storytelling taken from the Mexican muralists.

The Mexican government-supported public art program provided America with an idea for unifying its citizens using art to inspire change and connect people to a shared past, present, and future. In American murals and paintings, the heroes were the farmer, homesteader, and pioneer who endured struggle to gain land ownership and build communities and infrastructure for mutual benefit. Land ownership, religion, and the degree of government control were areas of difference between the Mexican and American art projects. Federally-funded competitions for American murals did not offer opportunities to engage with socialist subject matter given the government approval process. The public art program in the United States produced a picture of American values: family, community, various types of work, and an intimate knowledge of the diverse regions of the country. In American art of the 1930s-1940s, one feels the intense love of our country. It is a message sent through art from one tough time to another that might inspire us today.

[ TOP ]