November 14, 2024 - February 14, 2025

Installation Views | Essay | For availability and pricing, please contact the gallery at 212-581-1657

Installation Views

Essay by Emily Lenz

This exhibition considers how artists developed American abstraction in the 1930s and 1940s. Some were able to spend time in Paris while most followed developments through black and white reproductions in European art magazines. New York artists could see examples of European modernism at A. E. Gallatin’s Gallery of Living Art at NYU (opened 1927) or the Museum of Modern Art (opened 1929). In the early Thirties dealers like Valentine Dudensing and Pierre Matisse held exhibitions for Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró and other European modernists. The influential German painter Hans Hofmann held classes at the Art Students League in 1932 before setting up his own school in New York. He taught that the artist’s goal is to express the tension between three-dimensional forms and the two-dimensional surface of the canvas. Within the government-sponsored WPA, Burgoyne Diller’s New York City mural division was the only group that accepted abstraction. Like-minded artists met there and began discussing how to build an American audience for abstraction. This developed into the American Abstract Artists group founded in 1936. By its first annual exhibition in April of 1937, the group had 39 members. Each contributed non-figurative work in any abstract style including biomorphic and geometric. In 1939 the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (the early Guggenheim Museum) opened and became another place where New York abstractionists could show their work.

Twentieth century European artists distinguished their styles by developing theoretical distinctions and manifestos. For them, Cubism opened the door to many new branches of abstraction including De Stijl (Piet Mondrian), the Bauhaus (Wassily Kandinsky, Josef Albers, László Moholy-Nagy), and Abstract Surrealism (Miró). The Americans were more interested in ideas than theories and thus felt free to sample different styles and fuse together elements they liked. For example, the Russian-born painter Ilya Bolotowsky (1907-1981) saw Mondrian’s work at the Gallery of Living Art followed by Miró’s first exhibition at Pierre Matisse Gallery in 1932 and experimented with how to combine them, blending the restrained grid of Mondrian with the colorful biomorphic forms of Miró. This openness to synthesize two opposing styles demonstrates why American abstraction can be so fresh and innovative. The artists in our exhibition fall into three styles: biomorphic, geometric and spiritual. They all used the same formal elements of line, shape and color. The principal distinction is how each group treated depth in their paintings.

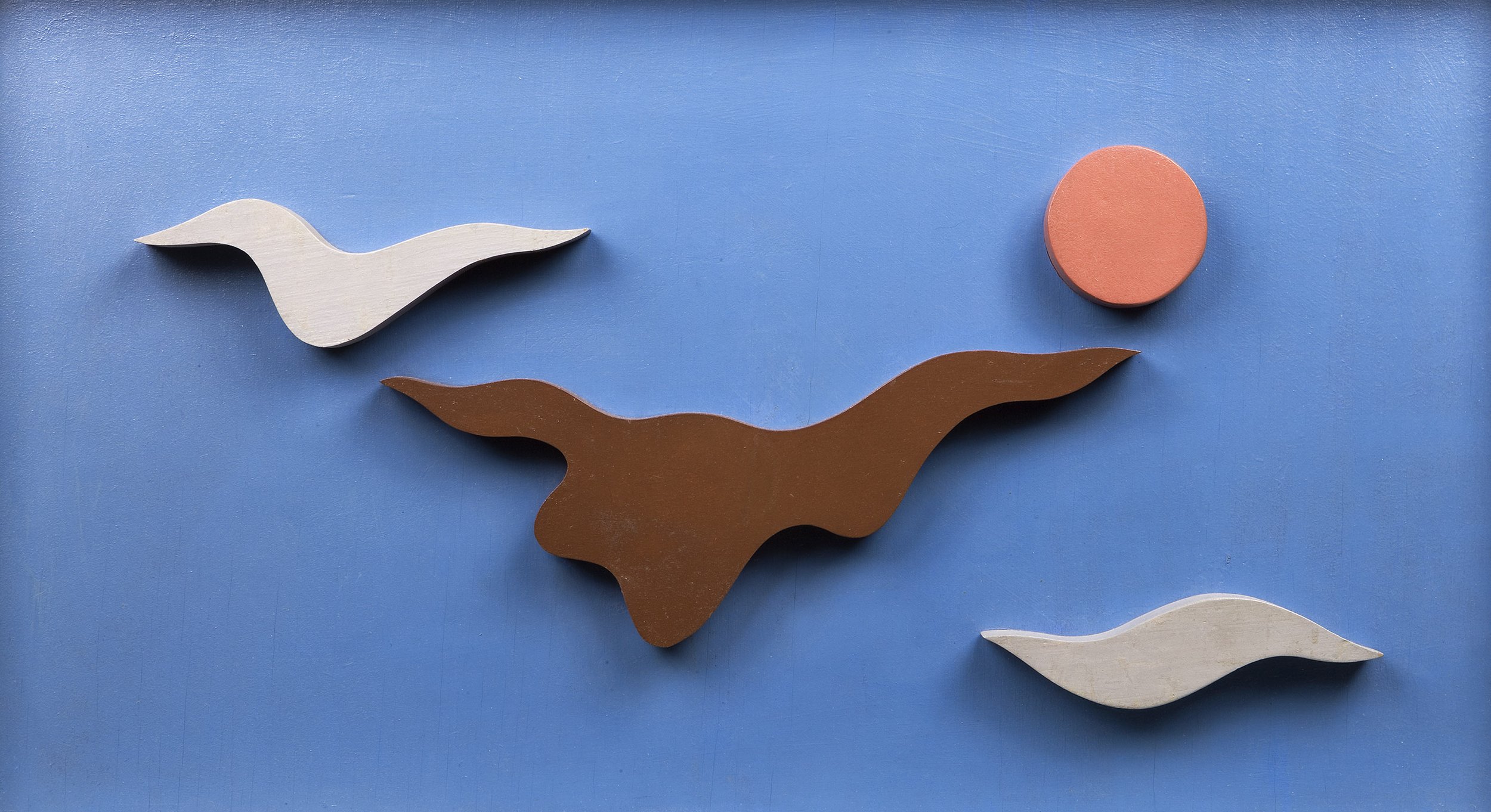

While Cubism set the path for abstraction, it was still based on observed figures or objects abstracted from something seen. Of the abstract styles, biomorphism is the closest to painting things seen as the term describes shapes that resemble but do not replicate natural forms. It is an organic rather than geometric approach to abstraction influenced by Miró. The Americans used biomorphism to explore sculptural form in the shallow depth of the picture plane. It helped many move through Cubism, taking from Picasso’s paintings symbols, shapes and lines to rearrange into their own compositions. The artists in our exhibition that most evidently evolved out of Cubism using biomorphism are Byron Browne (1907-1961) and George L.K. Morris (1905-1975). In Browne’s Still Life on Gray, 1945, the artist builds tension between depth and flatness with black calligraphic lines that form a structure accented by flat shapes in red, blue and white. The title suggests a tabletop arrangement, which the biomorphic forms make difficult to identify. In Morris’s two 1938 works Baroque and Concretion, shadows add a sense of realism to the flattened arrangements of shapes. In Baroque, the polka dots and patterns suggest Cubist collage. In Concretion, the black placed near the birch bark shifts the minimal shapes into three-dimensional forms in an indeterminate space. Both Browne and Morris used black lines throughout their compositions to provide structure to the layered biomorphic forms. Our exhibition offers two significant paintings with sculptural form by Charles Biederman (1906-2004). His floating forms suggest plant or sea life. The shallow depth of the picture plane emphasizes their volume. Biederman’s paintings show how the biomorphic style can be seen as Abstract Surrealism when the shapes and coloring feel otherworldly.

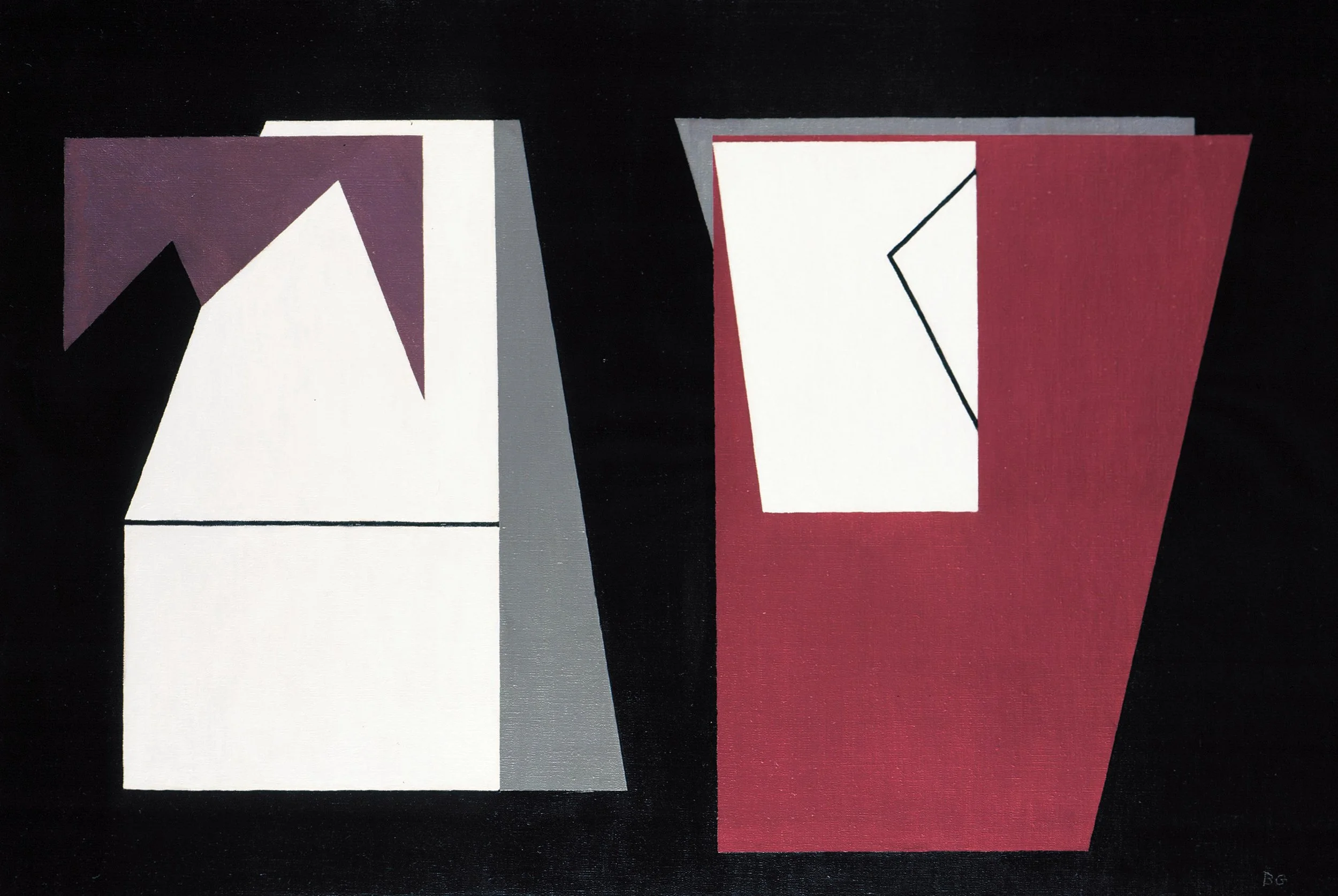

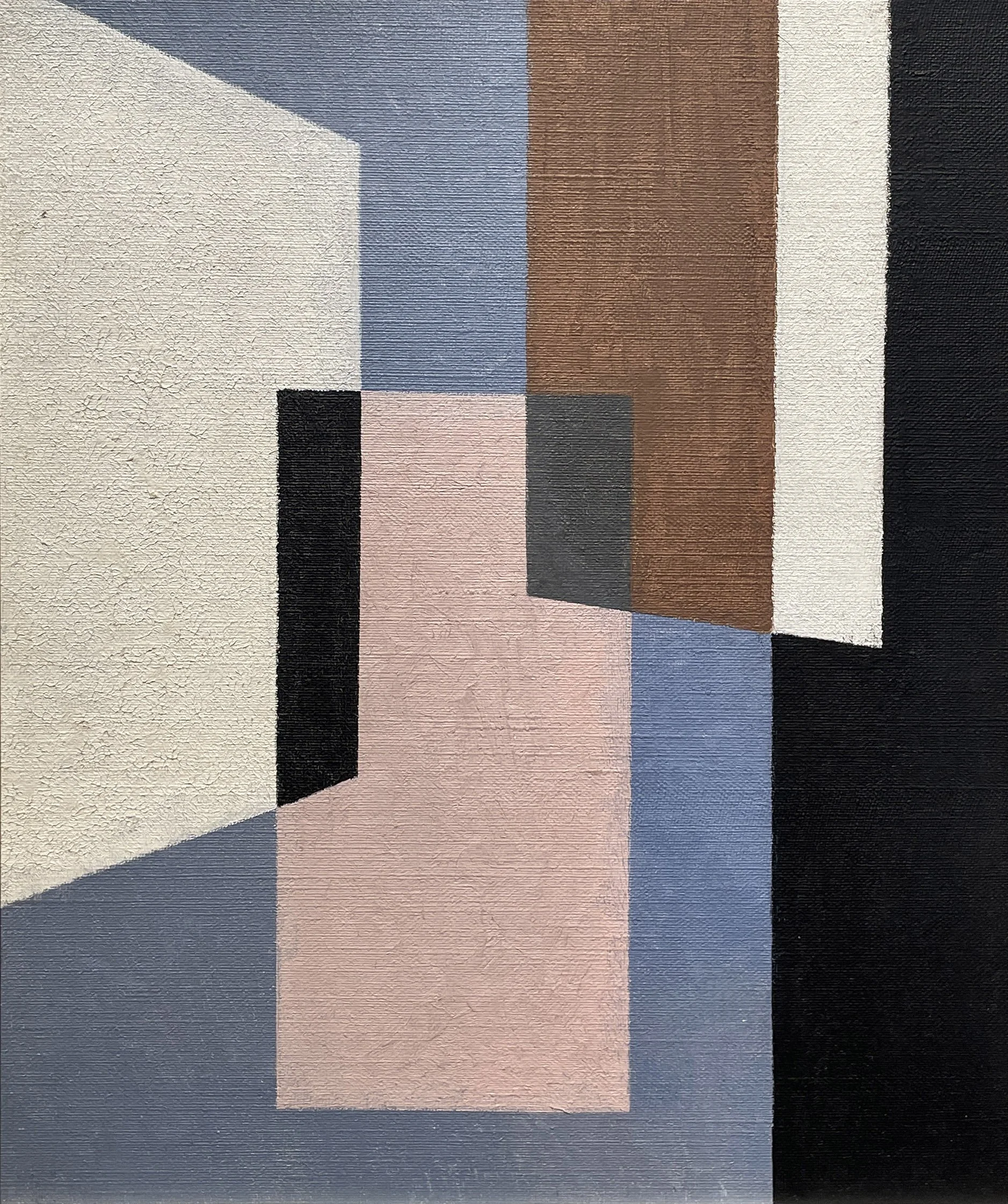

Geometric abstraction can be defined as the arrangement of shapes and colors within a flat picture plane. Artists working in this style in both Paris and New York in the Thirties called their work non-objective or concrete. They aimed for a universal language of lines, shapes and colors without connection to people, places or things. This style gained prominence as Bauhaus teachers Albers and Moholy-Nagy came to the US in 1933 and 1937 respectively, followed by De Stijl artist Mondrian in 1940. All three joined the American Abstract Artists and participated in their annual exhibitions. Charles Green Shaw (1892-1974) used the geometry of the city to evolve out of Cubism. We see this in the 1936 paintings Interplay and Structured Composition where overlapping vertical shapes rely on their relationship to neighboring forms to create surface tension instead of traditional shadows or receding colors. In Interplay, Shaw enlivens the gray field around the central rectangles by adding sand for texture. In Structured Composition, he activates the entire canvas with quadrilaterals extending to the edge, moving away from Cubism’s centered composition. Jean Xceron (1890-1967) uses shifting colors within each rectangle’s strong black outline as its own effect rather than creating three-dimensional form in Peinture No. 211, 1937. By filling the canvas with action from edge to edge, Xceron breaks the tradition of figure-ground realism. Our exhibition includes two paintings by Ilya Bolotowsky (1907-1981) that show his evolution into a more severe geometry in the Forties after Mondrian’s arrival in New York. In Blue Structure, exhibited at the Museum of Non-Objective Art in 1946, the buoyant and colorful planes reference Miró while the blue structure containing them has Mondrian’s rectilinear restraint. In Centennial, 1949, the grid extends across the full canvas and each rectangle contains complex color arrangements. This painting is surprisingly an abstract portrait of a mining town near where Bolotowsky taught in Laramie, WY.

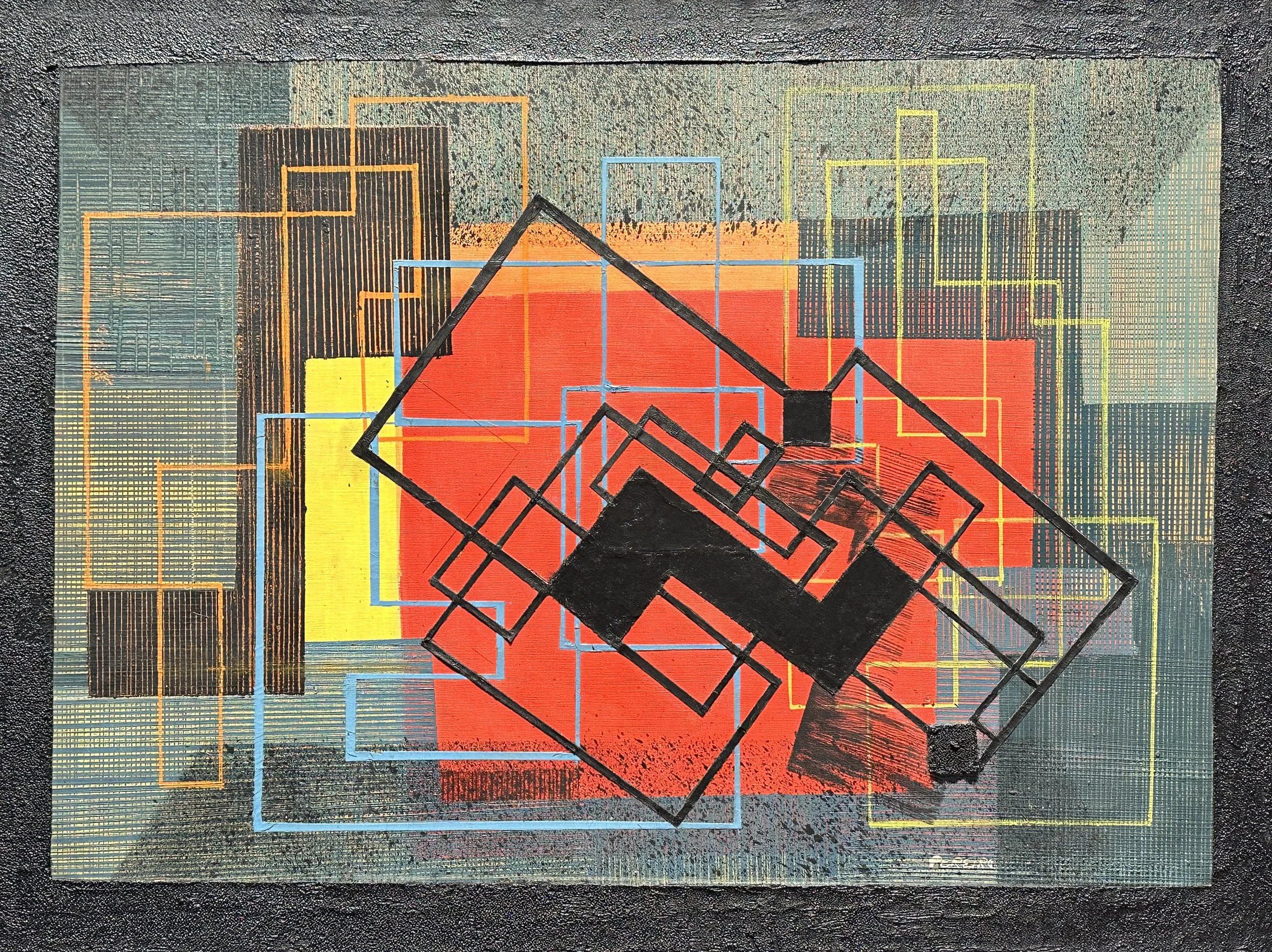

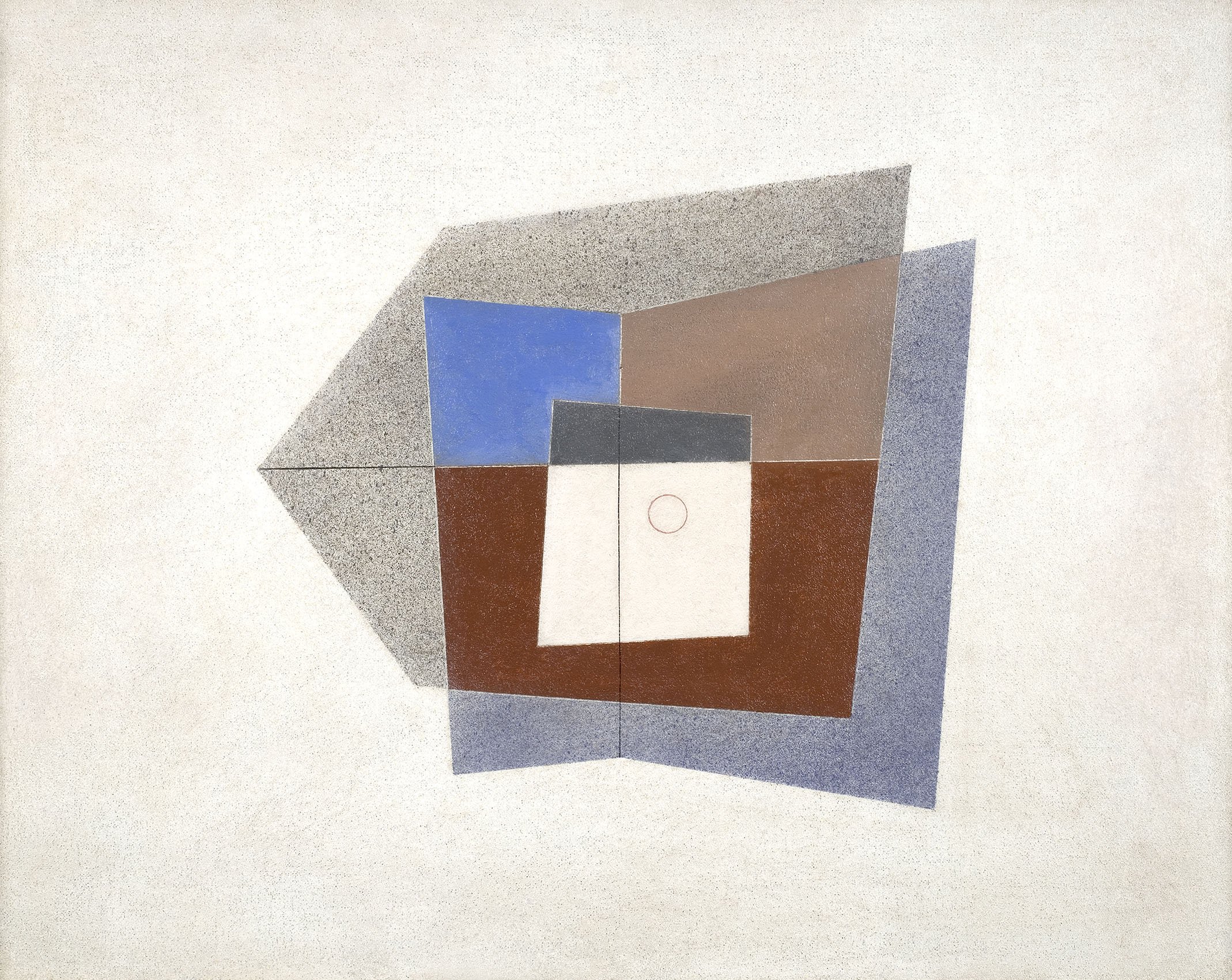

By 1940, a new development in geometric abstraction was spraying paint to experiment with depth and transparency. Harry Holtzman introduced the technique to Raymond Jonson and Charles Green Shaw in 1937-1938. At the same time, Moholy-Nagy arrived in Chicago and shared his vision of the future where artists use light and shadow effects projected onto a screen in place of paintings on canvas. This inspired artists to consider how to incorporate transparency into their current work. Shaw found the airbrush and motor too expensive, so he used stipple and spatter brushes instead in a 1941-1942 series including Square Divisions. Irene Rice Pereira (1902-1971) created her first pure abstractions in 1937-1938 as an instructor at the Design Laboratory, a WPA effort to create a New York Bauhaus for industrial design. Teaching from 1935 to 1939, Pereira used lessons from Moholy-Nagy’s The New Vision, translated into English in 1930, to make her students adept at working in a broad range of materials. Her students assembled collages that included rubbings of textured surfaces. Pereira incorporated these varied patterns into her first abstractions, distinguishing squares and rectangles in a composition with changes in texture. Pereira investigated transparency in her multilayered glass constructions starting in 1939 and then with translucent parchment in 1941. Pereira applied her new knowledge to paintings, as seen in Pendulum, c.1942 and Yellow Oblongs, 1945. In Pendulum, a solid black S-shape at the painting’s center is repeated as a transparent version at a different angle to imply a swinging movement. Another layer is made up of thin grid lines of orange, blue and yellow. Behind the S-shape and the grids is an arrangement of bold red flanked by orange and yellow. Pereira adds further complexity by spraying black trapezoids at top and bottom to emphasis the overall depth. In Yellow Oblongs, 1945, Pereira expertly uses sprayed and translucent layers to distort space, achieving on a single surface the same movement experienced in front of her layered glass works.

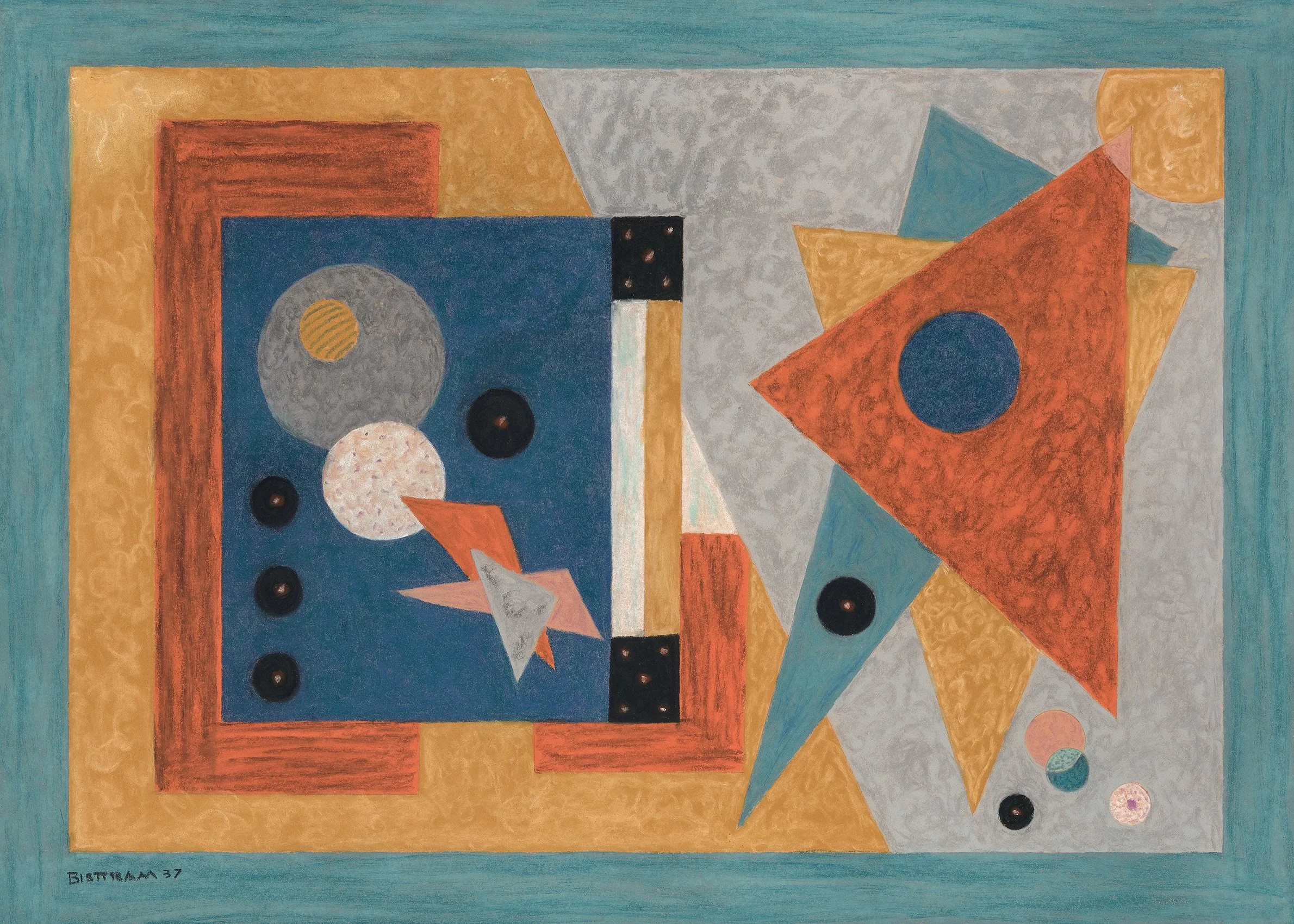

The artists that aimed for spirituality in their abstraction emphasized vertical movement to guide the viewer into higher realms of consciousness. The space in which the shapes and colors are contained is often indeterminant rather than flat or shallow. Kandinsky’s art was a source for this group. Kandinsky’s work was consistently shown from 1913 on; first at The Armory Show and then with Stieglitz in the Teens, with Katherine Dreier’s Société Anonyme in the Twenties, and by 1939 in the Guggenheim collection at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting. Many American artists working in the spiritual style exhibited alongside Europeans at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting in the Forties. The American artists read broadly, including on Theosophy and the teaching of Nicholas Roerich who established the Master Institute of United Arts in New York in 1920. Emil Bisttram (1895-1976) taught there and brought his learning to New Mexico where a group of artists formed the Transcendental Painting Group in 1938. Bisttram’s Celestial Alignment conveys this interest in broad spirituality as the light-filled circles reference the chakras while the vertical lines recall light seen through a prism. Our exhibition also includes Bisttram’s encaustic works that reference symbols and designs of Southwest Native American cultures. Werner Drewes (1899-1985) studied with Kandinsky at the Bauhaus in 1928 and the two exchanged letters until Kandinsky’s death in 1944. In Dynamic Center, 1940, arrows emphasize vertical motion and groups of short lines could be seen as steps to ascend, while the bright palette and circular movement of the biomorphic shapes create a sense of joy. Hilla Rebay (1890-1967) was an artist as well as the director of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting. She is represented by Delight, c. 1950 which lives up to its title with floating colorful orbs and moving ribbons of red and green. Rebay uses an atmospheric field of color as the background in which glowing yellow suggests dawn in the indefinite space. Maude Kerns (1876-1965), a West Coast artist, treats in a similar way her arrangement of geometric shapes that evoke Northwest designs, placing them at the center of a light-filled sky. Through their palette and forms these works are meant to provide the viewer with hope and a visualization of a greater universe around us.

While American abstraction of the 1930s-1940s mainly fits into the biomorphic, geometric or spiritual styles, the artists chose an abstract vocabulary rather than a strict philosophy, so in true American style many artists moved between these groups.

[ TOP ]

Modernism 1913-1950 | Realism of the 1930s and 1940s | Abstraction of the 1930s and 1940s | Post-War | Selected Biographies