Dec 4, 2019 - Feb 14, 2020

Read essay here. | Please contact the gallery at 212-581-1657 for availability.

Installation Views

Essay by Deedee Wigmore

Artists of different traditions and backgrounds reflect and shape our view of the American West, land of the rancher and the cowboy. So, when I was given the opportunity to offer collectors the western paintings of two successful American artists working during the Great Depression and World War II, I could not resist. The resulting exhibition is an exploration of the paintings of Adolf Dehn (1895-1968) in Colorado from 1938 into the 1960s and Peter Hurd (1904-1984) in New Mexico from 1928 forward. The 25 paintings hung in our gallery create a kind of a conversation between two artists who both captured the authentic West. These paintings provide more than a comparison and contrast of two very different western landscapes, they are a narrative of an artist's journey. Looking outward to select what the artist wants you to see, the artist also takes a journey inward. That journey reveals each artist's personality expressed through his selection of subject, painting style, artist tools, and choice of medium. The journey sculpts and shapes the art. These two artists stretch our thinking about western landscapes. In December, the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center held a symposium on "The Landscape Tradition Continued in the Western States" so we feel our exhibition of Adolf Dehn and Peter Hurd is timely.

As a youth in Waterville, Minnesota, Adolf Dehn knew he wanted to be an artist. He attended the Minneapolis School of Art from 1914-1917 and then accepted a scholarship to the Art Students League in New York, which he attended from 1917-1919. In 1939 Dehn was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for travel in the Far West and Mexico. One of Dehn's stops was a visit to Boardman Robinson who was teaching art at the Fountain Valley School and heading the art program at the Broadmoor Art Academy (now the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center), which combined an art school, museum, and theater. This ambitious program was successful because Colorado Springs was a major cure center for tuberculosis filled with wealthy patrons. Dehn had been a summer art instructor at Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri in 1938 and 1939 so Boardman Robinson invited Dehn to teach at Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center the summers of 1940-1942.

At the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, Boardman Robinson created an art print shop run by Lawrence Barrett, a master printer, who had come to Colorado Springs to recover from tuberculosis and stayed. Adolf Dehn had come to Colorado already a printmaker as well as a painter. At the Fine Arts Center, Dehn and Barrett connected and experimented with varied textures in Dehn's lithographs to enhance their realism. The work forged a partnership between Dehn and Barrett that lasted a lifetime. Dehn returned to Colorado regularly through the 1960s to pull prints with Barrett, leading to a body of Colorado subjects in watercolor and casein as well.

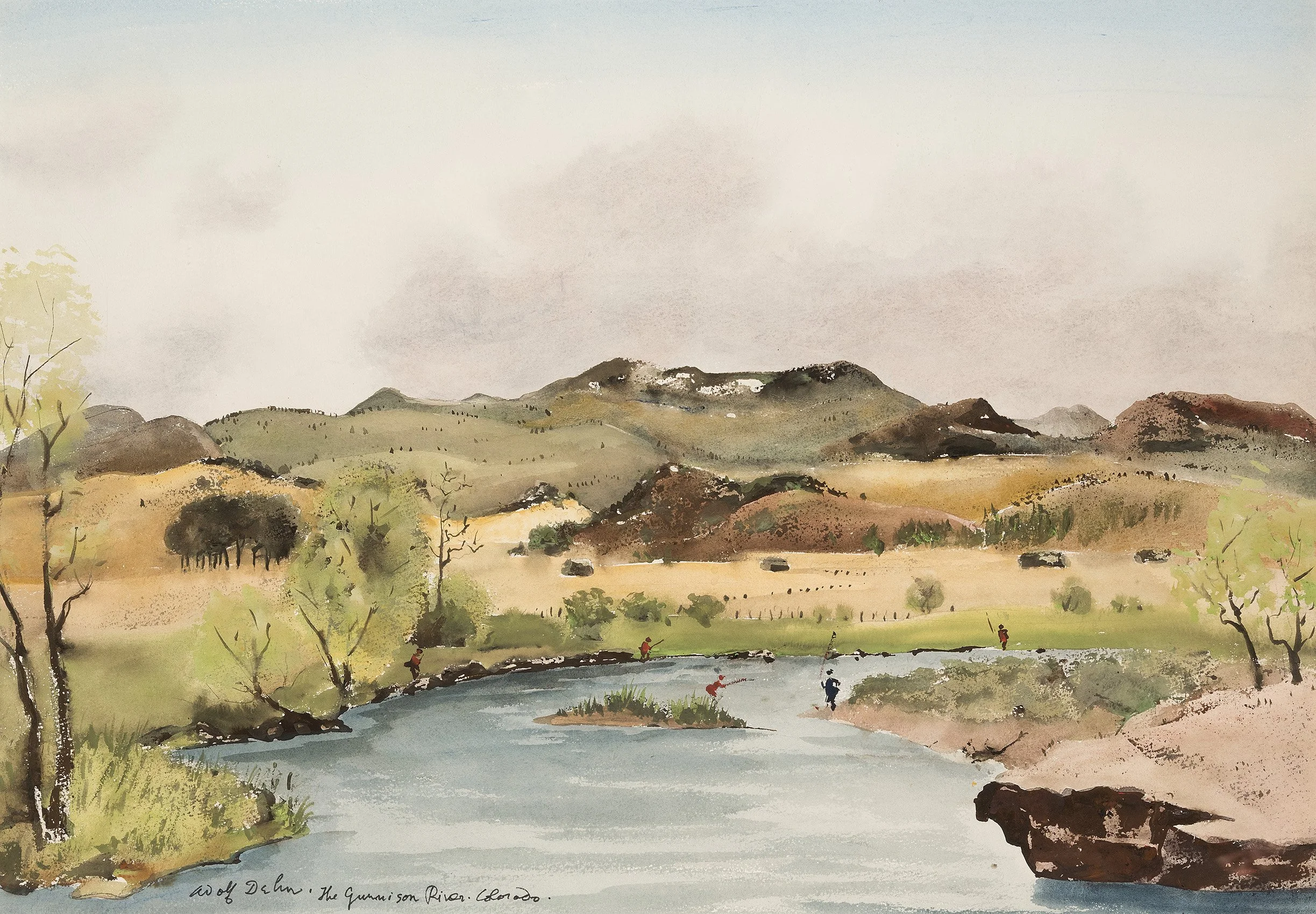

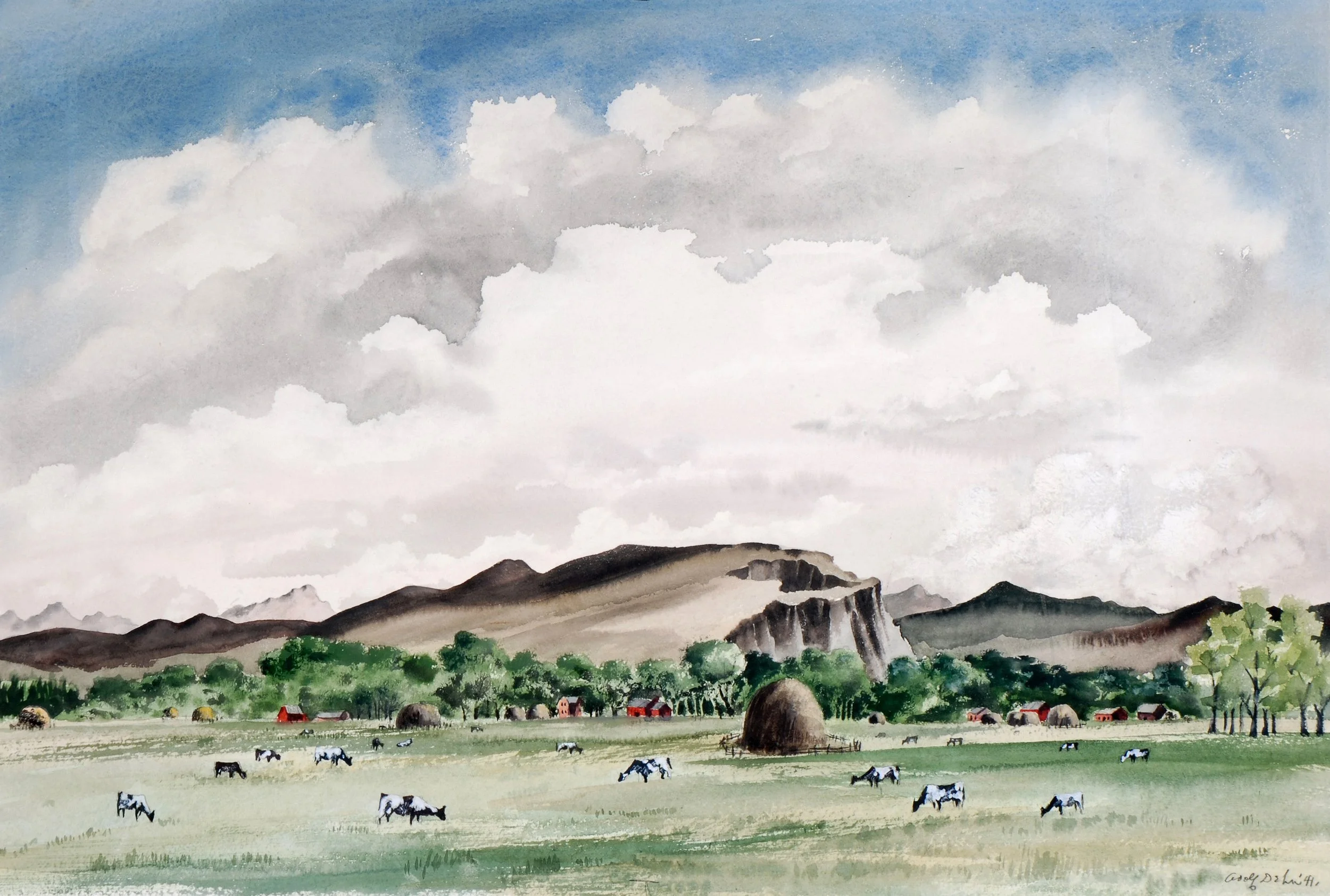

In Colorado Springs, Adolf Dehn reshaped his art from European-inspired figural social satire into landscape art of the new American Scene style as seen in Cows Grazing in Gunnison Valley, 1941. With Pikes Peak, the Garden of the Gods, and the Rocky Mountains at its door, Dehn could paint an America that exists outside of time, class, or political affiliation. Dehn's style transformation was aided by the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center's Artist-in-Residence Program which attracted artists who were instrumental in developing the American Scene style. At the Fine Arts Center, Dehn knew several of the visiting artists: Arnold Blanch (1896-1968) taught 1939-1942; David Fredenthal (1914-1958) assisted Boardman Robinson on a mural in the summer of 1936 and then taught the summers of 1940-1941; Yasuo Kuniyoshi (1893-1953) was a visiting artist the summer of 1941; and Doris Lee (1904-1983) was a guest artist from 1939 to 1941.

Painting the mountains and lakes required Dehn to go beyond the subject. He needed to think of big masses of color, light and dark, eliminating some detail for the sake of the composition, and even ignore the color before him at times to create a more exciting arrangement of color to evoke a certain mood or reaction to a scene. Dehn worked from an outdoor sketch, taking from ten minutes to two hours, depending on the complexities of the subject. He used either a soft pencil or lithographic crayon and a sketch book of smooth paper. Generally he did not make a finished drawing as his main interest was recording data for the painting he would later execute in the studio. Any part of the scene that was complex or difficult in its construction, he developed more completely. Color notes were written on the drawing. Sketching, rather than painting on the spot, allowed Dehn to develop a feeling about his subject and focus on the big picture without worry of changing light or weather. In the studio, Dehn considered the result of his color choices in different kinds of lighting, judging how a color and its different shades looked in the subdued light of a room, harsh light of overhead lighting, and in daylight. For the Colorado paintings, Dehn developed skill in the mediums of casein such as Mountain Landscape and watercolor such as Remote Ranch. Dehn found casein, a form of watercolor thickened with sour milk, gave paintings more body, a perfect medium for painting the crusty rock surfaces around Colorado Springs. As a printmaker he was already a master of ink wash, charcoal, and pencil drawing. Printmaking had taught Dehn to achieve a rich spectrum of tonalities and textures that blossomed in his Colorado paintings as seen in Gunnison Valley. By 1941 Dehn had such a sure hand as a painter that Life magazine made his art a feature in its August issue.

Peter Hurd (1904-1984) grew up in Roswell, New Mexico. His father Harold Hurd, a Boston lawyer, came to Roswell as he was threatened with developing tuberculosis. Peter Hurd focused on painting and drawing from youth. His education at the New Mexico Military Institute led him to spend two years at West Point as a cadet in 1921-1922. In 1923 Hurd transferred to Haverford College realizing he did not want a military career. While there, Hurd met N.C. Wyeth and with persistence became his apprentice. To improve his drawing, Hurd enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts along with N.C. Wyeth's daughter, Henriette. In 1927 Hurd became engaged to Henriette and began to exhibit his paintings at the New Mexico Military Institute and the Wilmington Society of the Fine Arts.

Peter Hurd brought his new bride, Henriette Wyeth, to New Mexico in 1929. He had achieved some success as an artist and was able to come up with $2,600 to purchase in May of 1934 a ranch of forty acres on the Rio Ruidoso with two adobe houses and an adobe barn. The ranch had water rights from the river to eight acres of orchards with apples and pears stored in one of the four adobe rooms. San Patricio was a village of a few families fifty miles west of Roswell. San Patricio's ranch country and people became Hurd's subject. All through the 1930s the Hurds traveled east to Chadds Ford for Wyeth family visits or to fulfill commissions for portraits, advertising, and book illustration. In the 1930s Hurd could not afford to do full time what he most wanted to do - paint the New Mexico landscape. He had to paint New Mexico when he could.

Like Adolf Dehn, Pete Hurd was a painter of the American Scene. To paint New Mexico Hurd had to develop practices and materials that gave him what he wanted. In New Mexico the earth forms assume a sharper contour, shadows are denser. Sunward surfaces are fixed in a dazzle of light. Heat waves in the summer make roads shimmer. The light makes color remain clear even at a distance. The sky is vast and may show several weathers at the same time. In the spring, winds bring weeks of heavy blowing dust. Our exhibition includes several paintings that speak of these moments of change so common in New Mexico. They include The Mirage and Finishing Chores Before the Rain. Peter Hurd described himself as "a painter of what occurs around me." The spirit of his landscapes is one of lyrical delight in the un-posed form, movements, and designs found in real life. From N.C. Wyeth, Peter Hurd learned to focus and become for a time whatever he was painting.

To translate what he saw in New Mexico, Hurd perfected the technique of painting in gesso with oil paints and egg tempera. Upon receiving his 1933 mural commission for the New Mexico Military Institute, Hurd traveled to Mexico City as well as Cuernavaca and Taxco to see the work of the Mexican muralists. There he got Diego Rivera's fresco formula, his type of brushes, paints, and advice from a Mexican fresco painter Ramon Montes. Hurd was attracted to dry fresco (the application of tempera onto dry plaster) as it combines all the brilliance of watercolor with the advantage of being readily wiped or dry sand papered out so passages could be redone. All sorts of efforts were possible using the dry fresco medium such as washes, stippled effects, smeared color, thin palette knife impasto, and glazes. From his understanding of mural painting, Hurd schooled himself to achieve a technique of an assured, restrained surface in his easel painting, using gesso as a ground on which to paint thin washes of oil and all the variety of applications he learned in tempera. The luminosity of the gesso ground creates the atmospheric brilliance essential to painting the light of New Mexico as seen in Rancho del Charco Largo. Hurd fashioned his own gesso panels with pots of hot sizing and marble dust applied to board paneling that he sandpapered many times. Hurd ground his own mineral colors. Hurd was so excited about this medium that he taught his brother-in-law Andrew Wyeth the technique as well.

While innovative in his painting techniques, Hurd aimed to subordinate material to subject, achieving this by the handling of space and objects in a spare way. To find subjects that moved him to paint them, Hurd drove a wide windowed camper truck over roadless plains and up flood carved arroyos in search of subjects. He made rapid field notes in watercolor on small blocks of paper rarely larger than 6 x 9 inches while driving and even smaller when riding a horse over his land. Hurd's farmscapes such as Rancho del Charco Largo were painted as symbols of human wishes, effort, and accomplishment. These abstract values are conveyed in his paintings and there is an undercurrent of acceptance of the fugitive in life. Hurd studied his designs for a painting in his mind's eye and rehearses his color in thought ó sometimes steadily looking at an unfinished work for hours considering changes to make, effects to be carried further, inner harmonies of detail to establish that would bring the picture alive as a whole.

Hurd grew up riding horses, took equitation at West Point and at Haverford College. When at Chadds Ford he rode with style and daring in horse shows and fox hunts with local clubs. Hurd's game was polo. He created his own playing field at San Patricio by clearing the cactus and rocks then bounding the area with goal posts. Hurd taught neighbors to play, enlisted guest players from the cavalry stationed at the New Mexico Military Institute in Roswell, recruited Mexican American cowboys and ranch hands from the valley, and made them into a polo team called the Beggars of San Patricio. They played against competition teams, both military and civilian teams from Roswell, El Paso, Fort Bliss, and Juarez. Peter captured one of those matches in a watercolor that is part of our exhibition titled Polo Tournament at Fort Bliss: San Patricio vs Juarez.

Success as an artist grew for Peter Hurd during the 1930s and 1940s. Hurd's first museum invitational was at the Corcoran Gallery in 1932. He had his first solo exhibition at Macbeth Gallery in 1934. In 1937 the Art Institute of Chicago purchased Hurd's El Mucho. Life magazine sent a photographer to photograph Peter Hurd at his San Patricio ranch in 1939. Hurd felt that it was not until he attracted the interest of the editors of Life magazine that he became known to the American public. In 1939, The Metropolitan Museum purchased Rancheria. From 1938 to 1942, Hurd spent time on mural commissions for post offices: Big Spring Texas; Alamo Gordo, New Mexico; and Dallas, Texas. In 1940 Steuben Glass commissioned Hurd to design a piece of glass. Hurd chose a windmill scene produced on a limited number of vases. 1941 saw a solo exhibition in New York at the Macbeth Gallery and the Tate Gallery purchase of Anselomo's House. Further cause for celebration were the two landscapes and a lithograph commissioned for Abbott Chemical Company's collection, a Life magazine commission, two commissions for Lucky Strike tobacco, and the cover of Collier's magazine. In 1942 Peter Hurd was made a member of the National Academy.

With America entering World War II, Peter Hurd became an accredited War Correspondent for Life magazine as a captain in the Army Air Corp. For one assignment, Hurd spent three months on an operational air station in England and executed nine portraits of combat crew members. When the portraits were published in Life in the July 26, 1943 issue, Hurd received one hundred letters from the airmen's families and friends. For a second assignment for Life, Hurd spent six months traveling with the Air Transport Command in 1943-1944, leaving him away from his ranch for eight months. Hurd recorded the creation of bases in remote places to provide a steady stream of men, aircraft, supplies, and hospitals for the war. Peter Hurd was awarded a European Theater Medal for Service in 1947. He spent 1952-1954 on a mural series at Texas Technological College in Lubbock. President Eisenhower appointed Hurd to the Commission on Fine Arts in 1959 and he painted a portrait for Lyndon B. Johnson for the White House Historical Association in 1966. Through all these adventures, Hurd was most happy painting in San Patricio.

[ TOP ]