May 20-October 16, 2020

Read essay here. | Installation | For availability and pricing, please contact the gallery at 212-581-1657

Installation Views

Essay by Deedee Wigmore

D. Wigmore Fine Art is pleased to present an exhibition of thirty paintings by two artists whose work was shaped by the landscape and Native people of the Southwest. Our exhibition presents the journey Raymond Jonson (1891-1982) and Emil Bisttram (1895-1976) took from realism to abstraction. The two joined together in 1938 to found the Transcendental Painting Group that raised them to national fame.

The Chicago artist Raymond Jonson spent four months in Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1922 and discovered there natural shapes and a rhythm in the landscape that he could use to develop his art. This visit resulted in Jonson and his wife Vera moving to Santa Fe in 1924 to build a home and studio on land they purchased. Exploring and sketching the landscape, Jonson was challenged by both his geological surroundings and the high contrast of light and shade. His solution was to approach his compositions using ratios indicated on the edge of his sketches. Jonson felt this mathematical approach led to divisions of the land and sky that held all the elements in balance. This practice gave a geometric framework to his paintings. Mountains with Snow, Santa Fe, 1925 in our exhibition is an oil painted in the first year of Jonson’s time in Santa Fe.

Earth Rhythms is the title of a series Jonson began in 1925 focused on unity in landscape formations. Jonson’s practice was to produce both oils and watercolors of closely related works in an open ended series. If inspiration suggested an addition in later years, Jonson added another painting to the series. Jonson also created trilogies and cycles of paintings so closely related they were conceived as a single work. From 1925 to 1929 Jonson attempted to liberate from the landscape what is significant from what is not and weave the spirit of the forms into a rhythmic whole. He employed color for establishing mood and to simulate natural light and shadow. New Mexico’s sharp contrasts of intense light and deep shade can provide a theatrical effect that is not always desirable. To record this light and avoid theatricality, Jonson focused on planes of color in gradation arranged to reflect the shapes, rhythms, and relationships of the landscape. Realistic pencil drawings were made in the field and stored as a source of forms and ideas for paintings. Our exhibition includes one of Jonson’s litho-crayon field drawings of Cordova Houses, 1927. Once in the studio, a field drawing would be adjusted through color selection to express the generalized emotion the location stimulated. The early landscapes of 1925-1928 incorporated local architecture in admiration of the Native Americans able to live harmoniously with nature. Jonson did not begin to incorporate ideas suggested by Native design and symbols into abstract compositions until the 1940s.

The 1920s was a period of development for Raymond Jonson. To provide income Jonson opened his Atalaya Art School in 1926 teaching a ten-week summer art course for three years. Times were lean but improved when Jonson joined an exhibition group of more established Santa Fe artists- Andrew Dasburg, B.J.O. Nordfeldt, Jozef Bakos, Willard Nash, and John E. Thompson in 1927. The group exhibited together in Seattle, Tucson, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Along with Russell Cowles and Olive Rush, the group of six artists also showed in monthly exhibitions offered by the Museum of New Mexico’s space for contemporary art. In 1928 Jonson’s career took off with a solo exhibition of forty paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, which traveled to the University of Oklahoma Museum of Art. The same year Jonson exhibited eleven works on paper at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. Additional income was provided by Vera Jonson who began working at the Spanish and Indian Trading Company founded by B.J.O. Nordfeldt, Andrew Dasburg, Witter Bynner, and John Evans founded in 1926 to deal in authentic Native arts and crafts. Vera already was collecting Indian crafted objects for their home. Jonson’s painting titled Indian Pot, 1924 shows one of Vera’s early purchases. When Vera died in 1965, the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico accepted 29 Indian objects to form the Vera Jonson Memorial Collection.

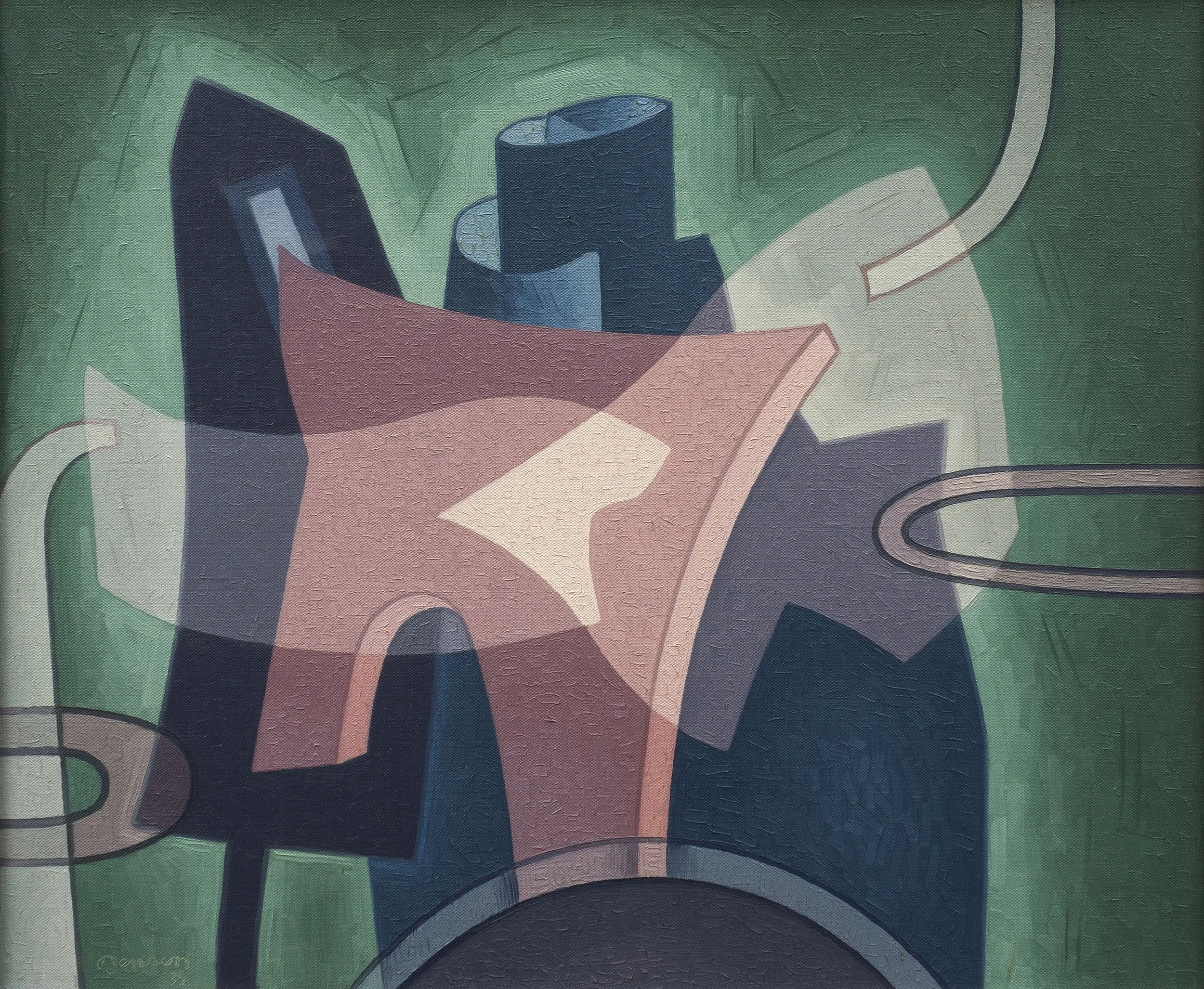

Jonson’s painting progressively became more abstract as he found compositional elements that connected the rhythmic structure of the work that had nothing to do with the landscape. This can be seen in a 1929 series called Growth Variants that explored plant forms and branched out into a group of paintings about growth patterns. This series helped liberate Jonson from the earth-sky format that dominated his landscape paintings. From 1929 to 1936, Jonson moved away from landscape-derived compositions and began working with shapes and abstract figuration in three further series: the Digit Series numbered one to ten, the Number Series, and the Letter Series of 26 works. The paintings in these four series were given a different color palette to add emotion to form and design. The paintings were exhibited in Jonson’s 1931 solo exhibitions in New York at Delphic Gallery and in Chicago in 1932 at Increase Robinson’s Studio Gallery.

In 1933 Jonson visited the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago and was impressed by mathematically-derived constructions he saw at the Hall of Science. He incorporated what he saw into his own mural commission for the University of New Mexico library in 1933, a part of the Public Works of Art Project. Inspired by the Hall of Science, Jonson created six large murals that make up The Cycle of Science: Mathematics, Biology, Astronomy, Engineering, Chemistry, and Physics. Jonson painted the murals in Albuquerque while commuting from Santa Fe. Also in 1933, Jonson was included in a three-person exhibition with Agnes Pelton and Cady Wells at the Museum of New Mexico. In 1934 Jonson added teaching one day a week at the University to his schedule. Mural painting caused Jonson to return to landscape subjects in three series titled Interlocking Forms in 1934, Universal Series in 1935, and the Cosmic Series in 1936. In our exhibition Synthesis Three demonstrates Jonson looking at the landscape and abstracting it into symbolic imagery. As he tried to release himself from land locked subjects, Jonson visited Agnes Pelton in Cathedral City, California in 1936. Both artists were working out how to express themselves with symbols and how to bring into focus an emotion. Pelton and Jonson connected through the painting subjects that interested them- space, color, shapes, and the sexual quotient in life. Jonson continued working on color relationships to explore the dissonance achieved through chromatic contrasts in series such as Dramatic Figuration and Prismatic Figuration. Jonson discovered that dissonance could be simple, subtle, complex, incidental, or central to a motif.

Working with ideas of how to move his art forward, Jonson met Alexander Archipenko and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy in Chicago during his solo exhibition at the Katherine Kuh Gallery in 1938. This meeting may have caused Jonson to abandon titling his works as paintings after 1938 are simply designated by medium, number, and year. The same year, Jonson joined the faculty of Arsuna School of Fine Arts in Santa Fe and began to use an airbrush for tempera and watercolor paintings. With Emil Bisttram in 1938, Jonson founded The Transcendental Painting Group of nine artists concerned with the development and exhibition of non-representational painting. The seven other artists in the group were: Robert Gibbroek, Lawren Harris, Bill Lumpkins, Florence Miller (later Pierce), Agnes Pelton, H. Towner Pierce, and Stuart Walker. While Pelton was not based in New Mexico, she had frequent correspondence with Jonson about the group’s formation and sent paintings for exhibition. The Transcendental Painting Group was invited to exhibit at the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco in 1939, which brought them national recognition. Hilla Rebay saw the exhibition and invited The Transcendental Painting Group to exhibit at the Guggenheim Museum in New York the following year.

At this high point in his career, Jonson became fully abstract, a shift partially brought on by his use of the airbrush. This artist tool facilitated the simultaneous movement of his ideas and emotions to execution. The airbrush also facilitated reliable luminous color without time-consuming brush work to augment color when oil paint had not dried as expected. The airbrush became a property of Jonson’s style in 1938 and led him to develop a new principle of color as the airbrush’s sprayed colors needed to be more closely related to attain unity. In painting with the airbrush, Jonson found he must pay close attention to the order, variation of shapes, and the rhythm of a painting’s intervals. The spacing, recurrence, and regularity in a painting also gained new importance in the late 1930s. These developments freed his abstraction to connect his paintings with Native art with symbolized themes by way of acknowledging the lineage of an idea. In these paintings Jonson began to express relationships found in Native art that connect the human world to animals, plants, places, and living and non-living spiritual elements.

The 1940s were a period of culmination for Raymond Jonson in his ability to fully express abstractly the New Mexico landscape, people, and their history. Our exhibition offers photographs from 1940 and 1941 of Raymond Jonson posed in front of his paintings which evidence his connection to Native art and design. This connection can be seen in numerous watercolors too, such as Watercolor #11, 1940, which connects earth and sky. In it four floating shapes of different sizes are connected by wind symbols above an abstracted design, which hints at a mountain rising below. Plant forms, figuration, and landscapes are merged in compositions such as Oil #2, 1941, an image of free invention with petal-like shapes connected by lines evocative of Native petroglyph symbols. Watercolor #21, 1941 in our exhibition has at its center a loosely rendered tall Indian figure facing a small cowboy figure. Both figures are composed of colored biomorphic shapes contained within the abstract background design of arabesques and ascending circles. The transparency achieved with airbrush in Watercolor #21 allows Jonson to express the interrelationship of things. The invention in Jonson’s 1940s art encourages a free interpretation of it. More obvious references to Native design began to be incorporated by Jonson in reaction to the art he saw. A series titled Pictographical Compositions in 1946-1947 demonstrates Jonson thinking about pictographs and petroglyphs in a series of seventeen paintings. There are also textural connections to Native design in the series with the use of an incised line and an admixture of sand with the paint in certain shapes. Jonson’s arrangements, adjustments, additions, and subtractions from Native American motifs made them his own and more about design organization than symbolic meaning.

The years 1947-1948 saw Raymond Jonson planning and financing the Jonson Gallery at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. In 1949 Jonson began teaching full-time at the University with the rank of professor. The following year the Jonsons moved to Albuquerque and the Jonson Gallery opened with a retrospective exhibition. Jonson’s painting practices once again changed in 1950. His improvisational approach to painting would in time lead him to gestural abstraction that grew out of his concern with the rhythm in a painting’s composition. Texture and artist tools became more important than subject to Jonson. The paintings that Jonson executed from 1950 until his last work in 1974 will be the subject of a future exhibition on how his use of new materials and new ideas connect to Postwar art. Over his lifetime Jonson had fifteen solo exhibitions at the Museum of New Mexico, Santa Fe. Jonson became an emeritus professor of art at the University of New Mexico in 1954, but continued as the Director of the Jonson Gallery until his death. The Archives of American Art microfilmed Jonson’s documents, manuscripts, catalogues, letters, and paintings in 1965. In 1971 the University of New Mexico conferred an honorary degree, Doctor of Humane Letters, on Raymond Jonson.

Emil Bisttram was born in Hungary in 1895 and immigrated at eleven years old with his family to New York in 1906. He began his career as a commercial artist and took night classes at the National Academy and the New York School of Fine and Applied Art. He married a Cooper Union graduate in 1920 and taught at the Parsons School of Design until 1925. At that time, Bisttram was offered a position at The Master Institute of United Art in New York by its founder, Nicholas Roerich. The Master Institute was dedicated to the translation of art into a spiritual and visionary language using order, rhythm, harmony, and unity and taught that everything an artist created must have quality to achieve the spiritual. In 1930 Bisttram and his wife spent three months in Santa Fe. The experience made Maryion Bisttram comfortable enough to set up a home there in 1931, renting the Eanger Irving Couse (1865-1936) home and studio while she awaited Bisttram’s return from Mexico City. Bisttram had won a Guggenheim Fellowship to work with Diego Rivera on the National Palace mural.

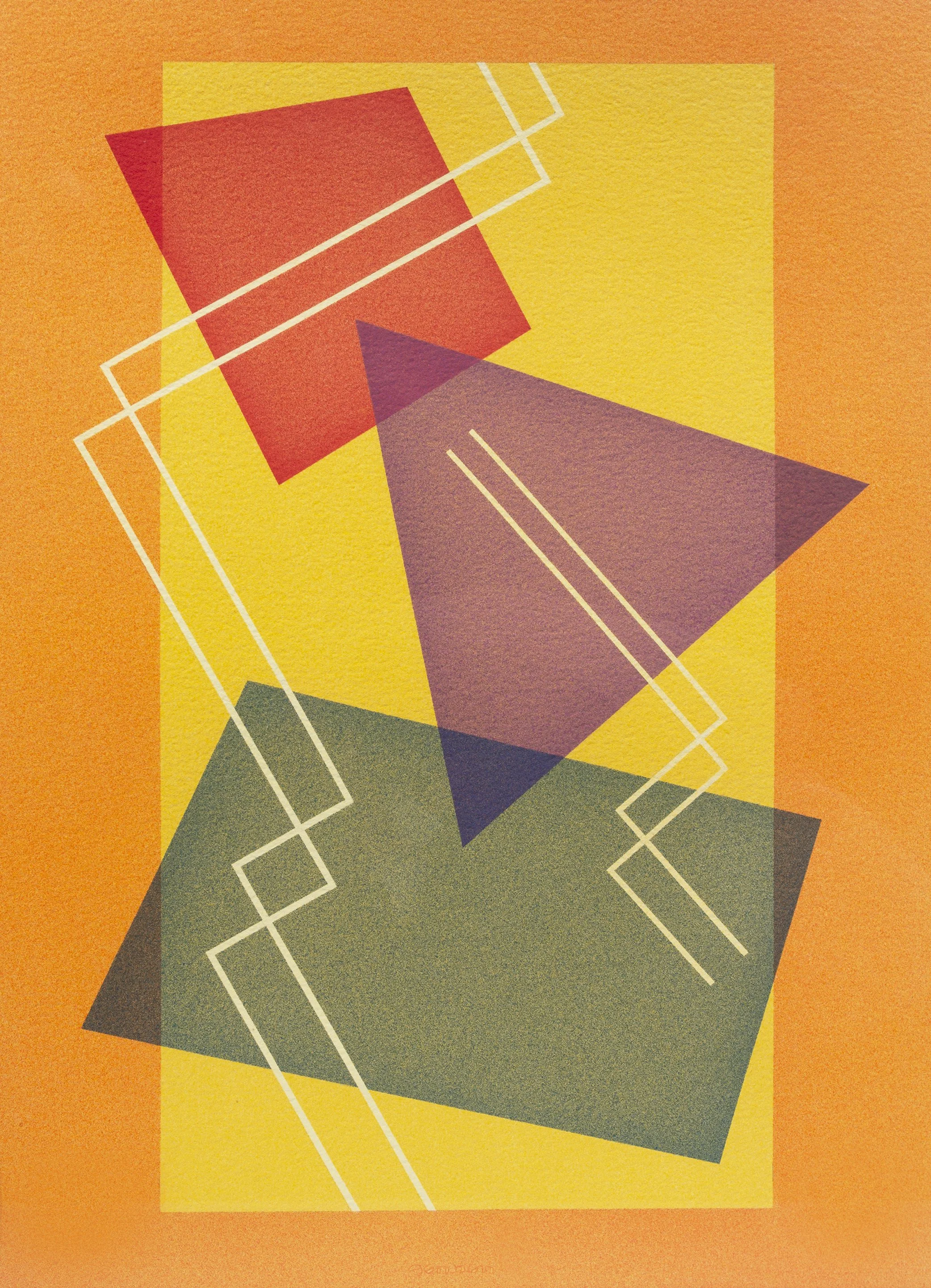

In Mexico Bisttram mixed paint and assisted in mural making in fresco. In scaling up Diego Rivera’s large figure drawings, Bisttram saw how they worked together in a geometrically conceived space. Rivera used both Dynamic Symmetry and the mathematics being promulgated in Paris by the Cubists to plan the composition of his realist paintings. Rivera designed his compositions in divisions ruled off to balance all the elements, following the principles of Dynamic Symmetry. Bisttram appreciated and understood that this system of designing a composition would work for both abstraction and realism. Rivera was focused on the renewal of Classicism to portray the history of the Mexican people in a symbolic way. His neoclassical figuration was similar to the figures Pablo Picasso was painting in Paris in the style of Ingres. Bisttram’s time with Rivera provided a new sense of clarity in form and pictorial organization. It completely transformed his ability to conceive and execute major figural works.

Bisttram rejoined his wife in New Mexico and set up a home in Taos in 1932. He immediately gave a series of lectures on his experience with Diego Rivera. Bistram set up an art school in Taos where Dynamic Symmetry was taught to give artists an approach to painting using mathematical divisions of the compositional space to achieve balance in weight, mass, and volume of the elements. Under the sway of Classicism, Bisttram painted portraits and figurative subjects rooted in symbolic, religious, and mystical concerns. As part of his teaching, he took his students to sketch at Pueblo ritual events. Bisttram’s work remained representational in the early 1930s as he painted portraits to examine the inner strength of individuals, choosing to focus on both Native Americans and Mexicans. These works took their inspiration from Diego Rivera and other Mexican epic painters. Bisttram attracted students to his school because he had numerous mural commissions. To complete his Guggenheim Fellowship, Bisttram had suggested creating a mural movement in the Southwest. Bisttram’s first mural commission was for the Taos County Courthouse. It was funded by the Treasury Relief Art Project in 1933 and resulted in Bisttram being offered the position of supervisor for the Treasury Relief Art Project in New Mexico, a position he held from 1933 to 1934. Bisttram won mural commissions in 1936 for both the Justice Department in Washington D.C. and the Courthouse in Roswell, New Mexico, as well as a mural for a post office in Ranger, Texas in 1937.

Bisttram had a solo exhibition of watercolors at Delphic Gallery in New York in 1933. The Delphic Gallery supported artists with metaphysical interests and held an exhibition for Raymond Jonson the year before. Agnes Pelton also had an exhibition there in 1932. Bisttram exhibited a series of watercolors titled The Dancing God Series. Hopi Calako Mana, c. 1933 in our exhibition may be from this series. The central Kachina figure in Hopi Calako Mana is surrounded by a border of Hopi sand painting symbols, marking Bisttram’s early interest in Native American imagery. By 1936 however Bisttram began to see Native art differently- as paintings about the human spirit that used symbolism derived from an abstract concept of nature and their gods to transcend the visible. Bisttram borrowed books on Indian ceremonial life from Dr. Edgar Hewett (1865-1946), the director of the School of American Archeology and the Museum of New Mexico. Reading and new thinking caused Bisttram’s paintings to become more abstract in order to give Native religious symbolism greater emphasis in his work. He toured the rugged Navajo country in western New Mexico making thumbnail sketches and learning how to reduce the landscape elements to a bare minimum. His approach to painting the landscape was less about the beauty of the earth’s surface and more about probing the structure that integrated mountain and mesa into a living whole. Bisttram, like Raymond Jonson, discovered that abstraction was a way of dealing with the brilliant Southwestern sunlight and overwhelming landscape. Bisttram credited his use of symbols to tell a story or portray an emotion as something that came out of exposure to Southwest’s Native American paintings combined with Wassily Kandinsky’s influence. An expression of Bisttram’s new kind of symbolism is found in the logo for The Transcendental Painting Group he created in 1938. The motif of the logo is a circle within a circle at the top of the logo, symbolic of the eye of animals and represents the hypnotic influence of nature and the priority of primitive art for the Group. Our exhibition offers examples of Bisttram’s Native American inspired abstraction in works like Connecting Rhythms, 1936, as well as figurative abstractions such as Kachina Dancer, 1939.

From 1936 to 1947, Bisttram worked in the encaustic medium, a wax/resin mix that is referred to in Ancient Greek writings, for his works on paper. Little is written about Bisttram’s use of this medium but he may have learned to work in encaustic during his three months with Diego Rivera. Rivera turned to encaustic after he failed to find the ingredients to make Italian fresco painting work in Mexico. Rivera had seen fresco painting while in Italy and then studied Renaissance artist Cennino Cennini’s writings on the medium. Rivera turned to encaustic, which called for heating beeswax and mixing pigments into the liquid paste, for his first mural commission: the Bolivar Amphitheater in the National Preparatory School in Mexico City. Rivera believed encaustic to be a durable and long lasting medium to match the significance of his commission. It was an intensive process that required his assistants use blowtorches to keep the wax warm while Rivera worked. Eventually Rivera found a local alternative to Italian fresco in the ancient Mexican city of Teotihuacan. While Rivera gave up the encaustic technique for his murals, he continued to use it in easel paintings. Thirteen of 56 paintings in Rivera’s 1931 solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York were encaustics. Bisttram liked created a drawing stick of wax and powdered pigment for the crisp lines and clear block-lettered signature that appears on all the encaustic works. In his encaustics, Bisttram broke with Dynamic Symmetry to offer an all-over design rather than a balanced linear arrangement. Our exhibition has three further works executed in encaustic on paper in 1939: Kachina Moon, Combat, and Geometric Divisions. We offer numerous encaustic paintings executed by Bisttram from 1940 to 1947 to show his continued interest in Native American culture and design as a source for his art.

At the time of founding the Transcendental Painting Group in 1938, Raymond Jonson and Emil Bisttram had both progressed to full abstraction for the purpose of carrying paintings beyond the physical world through new concepts of space, color, light, and design. Our gallery exhibition has focused on art by the founders of the Transcendental Painting Group to tell the story of their journey from realism to abstraction. The Transcendental Painting Group lasted as a group of nine until 1941. Bisttram moved his Bisttram School of Art seasonally to Phoenix, Arizona in 1941 as World War II came on and then to Los Angeles in 1945. The Bisttram School located at 636 South Ardmore at Wilshire Boulevard was redesigned to teach young artists serving in the armed forces or those working in defense plants. The School offered a four year course in Fine Art, Advertising, and Illustration, as well as summer sessions in Taos, New Mexico. Bisttram taught and painted both realist and abstract styles using his paintings to explain points he made in his teaching. Four of The Transcendental Painting Group- Gibbroek, Miller, Pierce, and Lumpkins- followed Bisttram to Los Angeles and worked in his school. At the war’s end Bisttram returned to Taos. Bisttram, like Raymond Jonson, continued to be productive in the 1950s. In 1952 he founded the Taos Artists Association. The Association honored Bisttram in 1968 with an exhibition Taos Collects Bisttram of fifty-six oils and watercolors at the Stables Gallery. In 1970 Bisttram was named to the New Mexico Arts Commission by the governor of New Mexico. In 1975 the governor of New Mexico proclaimed an annual Emil J. Bisttram Day in New Mexico. Bisttram died in 1976.

[ TOP ]