Essay by Emily Lenz

D. Wigmore Fine Art, Inc. is pleased to present with the family of William Hunt Diederich (1884-1953) a selection of works that show Diederich’s mastery of many media from 1914 to 1929. On view January 6 – February 13, 2016, the exhibition includes sculpture, metalworks, ceramics, silhouettes, and drawings. Diederich was a modernist who expanded the meaning of sculpture to keep it relevant in the 20th century. In his first major New York solo exhibition in 1920, he said, “Personally I like to work in as many different media as possible. Sculpture has too long been an affair of marble and bronze. It is too remote, too inaccessible. We must do everything possible to extend its scope and appeal, to insure for it a wider, more popular appeal.” Diederich succeeded in his goal and his fire screens, weathervanes, and lighting are coveted for their charm, elegance, and craftsmanship.

Hungarian-born Hunt Diederich’s fusion of German and American Western cultures is often discussed, yet that reading is too limited for Diederich’s cosmopolitan upbringing. His mother Eleanor was the second child of the Boston artist William Morris Hunt (1829-1879). The young Diederich took advantage of being a part of an artistic family. By 1910 when Diederich made his Paris debut, he had attended Swiss boarding school and Boston’s prestigious Milton Academy, trained with the preeminent French animalier Emmanuel Frémiet, worked as a cowboy in Wyoming, traveled through Spain with his good friend Paul Manship, and gained inspiration from textiles and ceramics he had seen in North Africa. Diederich’s choice of materials were as broad as his travels and with basic materials he elevated functional objects into works of art. Diederich was drawn to traditional folklore narratives, exploring in his silhouettes and fire screens subjects from Don Quixote, the Renaissance, Russian peasants, and African hunters. He was just as interested in new mythic-like symbols of masculinity and found the Spanish toreador as exotic as the Western cowboy or the New York boxer. Travels to Morocco and Mexico to study their rich ceramic traditions resulted in Diederich’s creation of pottery throughout his career; two examples are included in our exhibition.

Hunt Diederich’s formal art training included two years at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts where he and fellow student Paul Manship became great friends. The two traveled through Spain in 1908, a creative and competitive summer Manship recalled with fondness. Perhaps this is why Diederich gave Manship the dueling warrior andirons included in our exhibition. The andirons appeared in a well-illustrated article on Diederich in New Country Life in 1917. The caption for the andirons reads: “The hinged tops may be bent down to keep dishes warm over the fire.” An example of how Diederich strove to bring beauty to functional objects, aligning himself with the Arts and Crafts tradition.

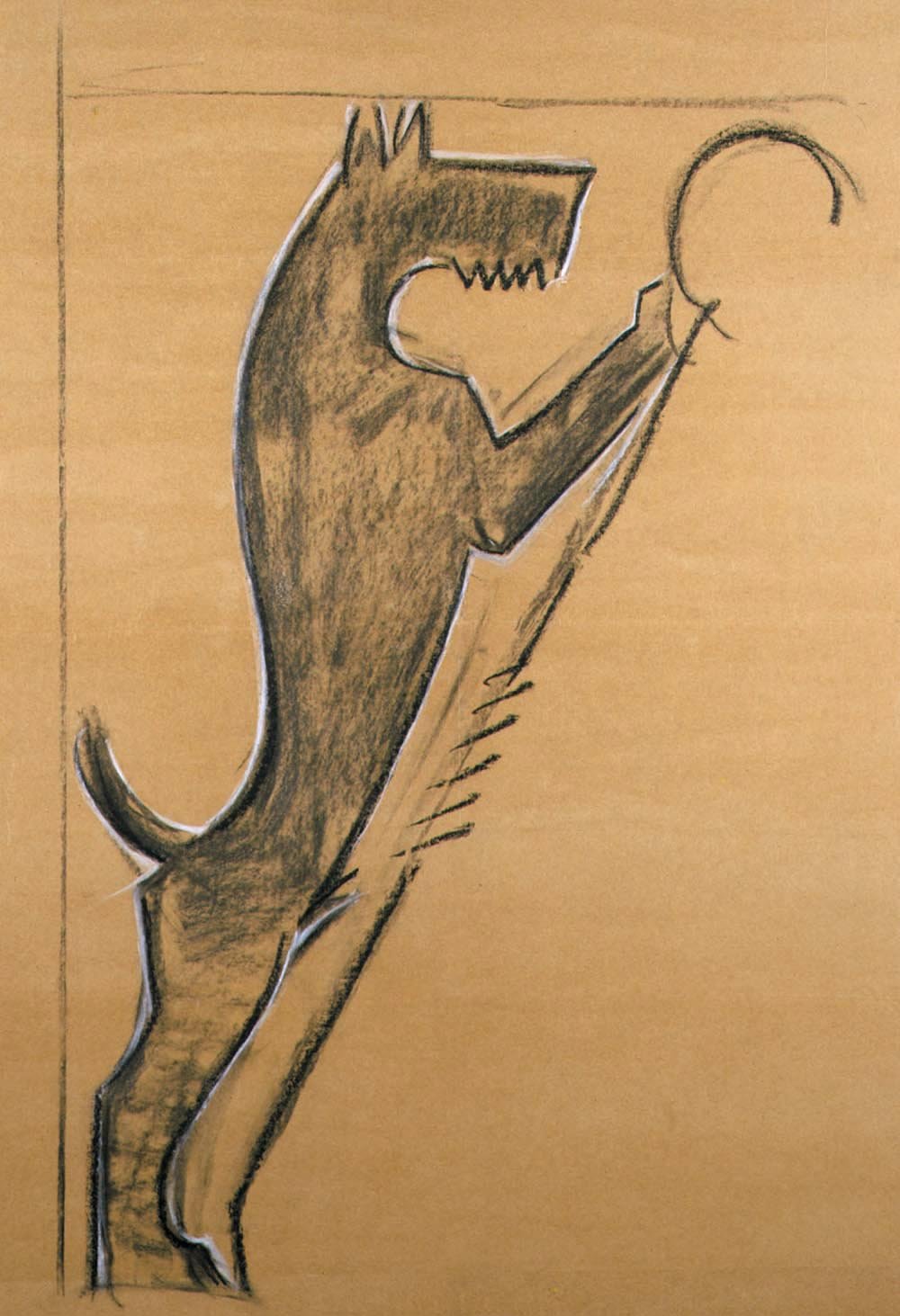

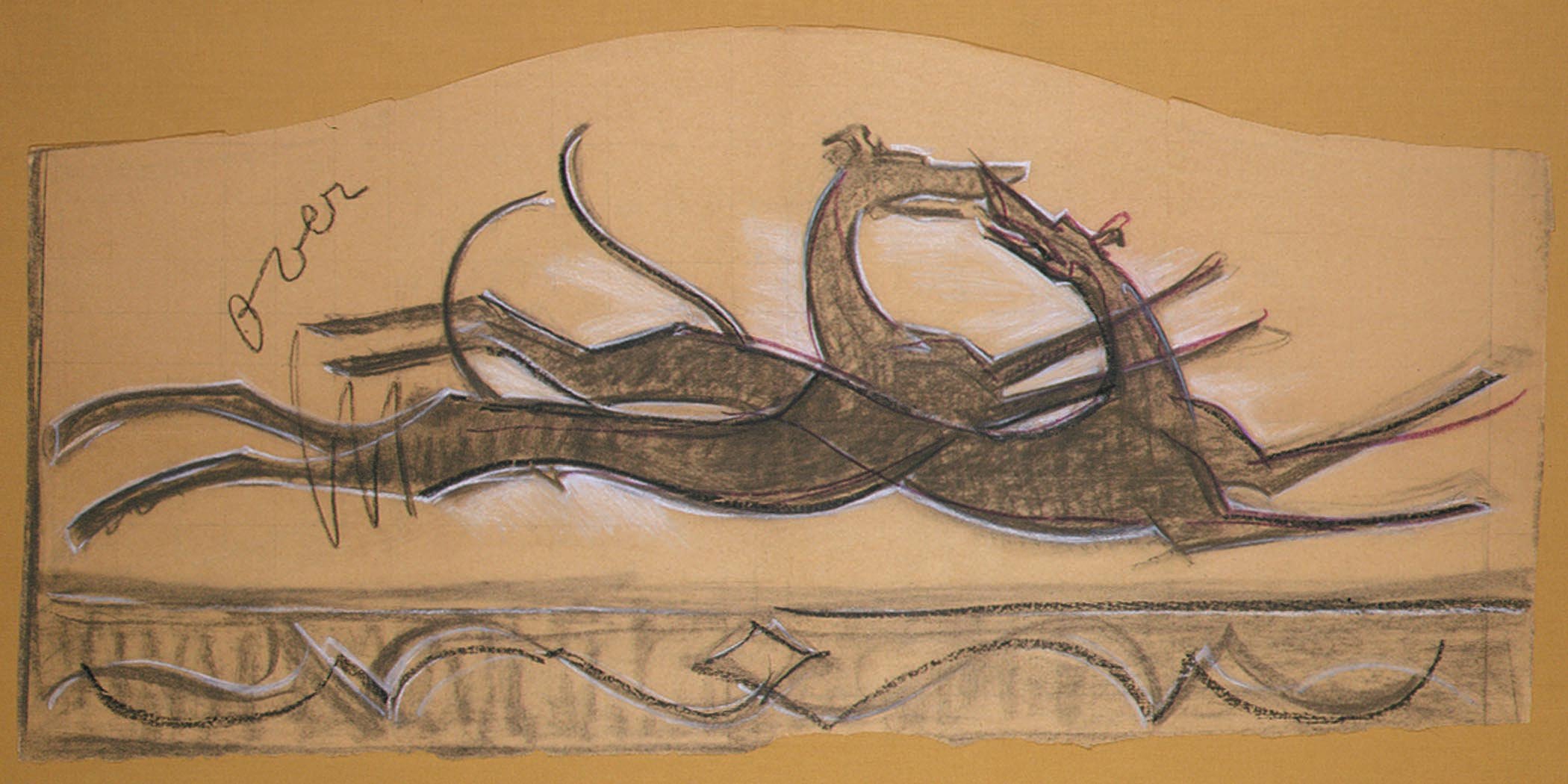

Hunt Diederich made his Paris debut at the Salon des Indépendants (the Spring Salon) in 1910 with two cast cement sculptures. His unusual materials were noted by the critic Clément Morro in Revue Moderne. In the current Picasso sculpture exhibition at MoMA, Picasso is given credit for his modernity in the 1930s for elevating the common building material when he cast his Boisgeloup plaster sculptures in cement. Diederich continued to innovate in the Teens with functional objects like brackets in cast iron and lively weathervanes in cut metal. Diederich developed his unique style through silhouettes, a practice he credited to childhood diversions in the German and Swiss tradition. Silhouettes provided a way for Hunt Diederich to focus on movement rather than mass to depict the energy of the animals he loved. Diederich’s mature style elongated forms into an Art Deco aesthetic with crisp lines that translated his silhouette forms into metal weathervanes, chandeliers, and most importantly for fire screens. In our exhibition one can see the fluidity of Diederich’s style between media with Two Greyhounds in the Round, a black paper silhouette accented with a gold outline, and Horse and Hare Trivet with similarly intertwined forms cut out of metal. The shape of the silhouette Strutting Rooster is also seen in Fighting Cocks Charger created at Diederich’s pottery at the Woodstock Arts and Crafts colony Byrdcliffe in 1929.

Diederich was drawn to folk culture and the elemental desire of humans across the ages to enrich their lives with beauty. For this reason, the best of Diederich’s work has a modern simplicity and energy that engages us today.

[Top]

Modernism 1913-1950 | Realism of the 1930s and 1940s | Abstraction of the 1930s and 1940s | Post-War | Selected Biographies