Nov 16, 2015 - Feb 13, 2016

Essay | Selected Exhibitions and Museum Collections | New York Times Review

All art by Sally Michel: Ⓒ 2015 The Milton Avery Trust / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Essay by Tom Wolf, Professor of Art History, Bard College

Sally Michel lived her life dedicated to making art. She decided on that goal when a teenager, and pursued it with determination and dedication. This is what attracted Milton Avery, seventeen years her senior, when he met her in Gloucester in 1924, and what charmed him to pursue her to New York to woo and marry her. Together they formed an indissoluble unit until the time of his death in 1965. They lived together, had one daughter together, travelled together and painted together. Her vivacious personality complemented his taciturn manner. From extensive interviews with her it is clear that she was convinced that he was a great artist, and that she had no problems having him seen as the front man in their artistic relationship: “I wanted all the spotlight to be on Milton.” (1) She believed that his were the best paintings that could be made at the time, and hers were coextensive with his. They shared the same style of simplified forms and thinly brushed areas of expressive colors, approaching abstraction but always retaining an element of recognizable imagery rooted in the experiences of everyday life. (2)

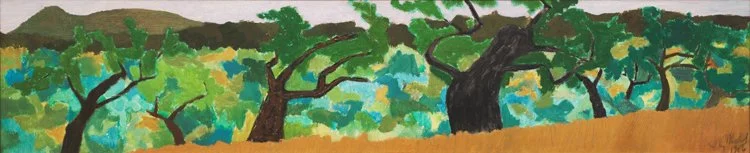

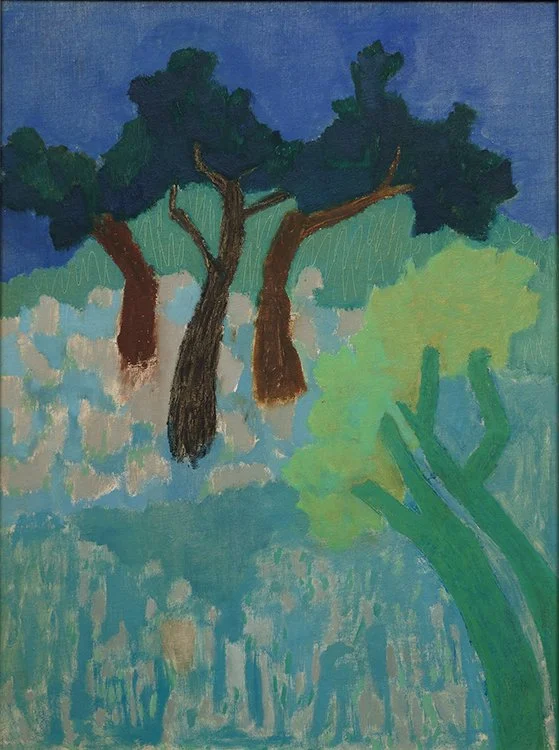

Within these parameters she achieved a wide range of expression, as can be seen in some of her landscape paintings in this exhibition. In a scene set in Provincetown where an elevated shed sits by the edge of the sea Michel rendered the objects as flat profiles, including the birds on the roof and the echoing sail boats in the water. They become vehicles for a rich play of muted colors, dull greens, tans, browns, subtly ignited by a thin band of blue water. In contrast Spring Forest erupts with bright color as Michel put pale purple bushes in dialogue with yellows and electric blue foliage. In Dense Forest with its blue tree trunks and orange and red earth Michel pushed her arbitrary, intuitive color to extremes that approach Expressionism. The hotly hued scene is divided into a few frontal planes, similar to the three horizontal bands that comprise Spring Landscape and Wooded Shore. The frontal planes of loosely brushed, luminous color remind us that in these years the Averys were close friends with the up-and-coming Abstract Expressionist painters, Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb. The tripartite structure of Wooded Shore, with its horizontal planes of pale green, blue and yellow tied together by upright meandering lines that represent tree trunks, recalls Rothko’s mythic watercolors from the mid 1940s. Similarly in Birds the combination of the slender band representing the water at the bottom and the vast, bird-filled sky, resembles some of Gottlieb’s pre-Burst abstracted landscapes. But Michel always retained a reference to recognizable nature, which she sketched from almost daily. The figure in Woman by the Lake stands in for the artist, quietly contemplating the beauty of nature that surrounds her. Her pale lavender arm resting at her side is both a complicated abstract shape and a form that clearly expresses the anatomy of the arm and its function. This is one small example of the skill in drawing that inspired Michel’s passion for art when she was just a young child, and that was a central part of her practice as an adult artist. Her Guitar Player is rendered as a series of flattened, simplified forms, her skin an unnatural grey. But her pose, seated, leaning forward, head bowed towards her instrument, conveys her immersion in the music she is making, another example of Michel’s ability to convey real life experience with extremely distilled drawing.

For decades her husband had the freedom to spend his days painting because she was working as a commercial illustrator to support them. Thanks to her drawing talent she had a steady stream of work. She supported her family through her art, unlike many of the other artists’ wives, or for that matter, male artists in her circle. During the Depression when Avery was on the government’s WPA aid to artists program he would get $35 for a painting, which was about what she was making per hour for her commercial work. (3) Early on in her marriage to Avery she had jobs illustrating for Macy’s department store, the magazine Progressive Grocer, a trade publication founded in the 1920s that is still in business, and the Cannon Towel Company, among other clients. Her large, lively Cannon Towel poster, with its bright flat colors and assertive words, bridges the gap between the posters of Toulouse-Lautrec and Pop Art.

Her most consistent employment was illustrating the “Parent and Child” column that appeared weekly in the New York Times, a job she held for most of two decades, from around 1940 to 1960. When she retired from this job due to Avery’s failing health, the Times discontinued the column. (4) Michel earned the respect of her fellow artists by having a steady income that was a product of her artistic skills. As she said, “it’s possible to be a commercial artist and yet have a fine arts attitude.” (5) Working in the world of commercial art to support her fine art practice allied her with other American women artists of the period, like Peggy Bacon, Esphyr Slobodkina, Mabel Dwight, and Michel’s good friend, Doris Lee.

Michel’s “Parent and Child” drawings reveal her talent for communicating narratives visually, a skill shunned by the progressive artists who were moving towards pure abstraction. A few examples of her original ink drawings for the 1957 “Parent and Child” column have been preserved and they show her skill at capturing human experiences and conveying everyday dramas with a concise vocabulary. Made for reproduction in the newspaper, her images are exclusively black and white. Like her paintings, she built her images of juxtapositions of flat forms, with no shading and occasional perspectival passages, plus a sophisticated handling of patterns. These limited means relied on her closely observed insights into the behavior of children, and their interactions with adults.

Michel and Avery had one daughter, March, born in 1932, and raising her exposed Michel to the activities of children and parents in the first half of the 20th century. Beyond that she clearly was a perceptive observer of human experiences of all ages, as evidenced by her drawings. In one scene a sympathetic counselor meets with two concerned parents over a report card that displays grades of C, D, and F. (6) A symphony of patterns articulates the image and gives it visual punch, while the body language and concisely rendered facial expressions of the figures communicate the concern of the three protagonists. The father, as in all these illustrations, is a dapper version of Milton Avery, tall and thin, always with a moustache.

Another little known facet of Michel’s art is that she made many portraits of her artist husband, works on paper with a striking range of moods, executed in a broad variety of styles and media. There are probably several hundred of these, and they have rarely been seen. In some he is calm and peaceful, but others are almost Expressionist in their expressive color and distorted physiognomies. In 1949 Avery suffered a major heart attack and suffered from poor health for much of the rest of his life, and the intensity of these works seems to express his struggles as well as her empathy. She was both his caretaker and his companion, and true to Avery/Michel practice the subjects of her art came directly from their shared everyday lives.

In Horse Jumping from around 1955 Michel created a luminous landscape where two horses with riders face each other in profile, the one on the right leaping over a hurdle (Fig. 14). The hurdle, the only perspectival element in the painting, is set against flat bands of land, mountains and sky, each rendered in poetically unrealistic color--witness the pale blues of the ground and the light orange sky. A comparable scene of a girl and a boy on galloping horses appears in a book she illustrated in her role as a commercial artist. (7) Comparing the two reveals the relationship between her art and her illustrations. The couple in the book is also rendered flat, with no modeling; the horses are also seen in profile. But the black outlines surrounding the images make them more graphic, less pure painting. Horse Jumping is typically thinly painted, but Michel also used the physical texture of the paint to expressive effect, with horizontal strokes of the brush visible in the blue ground and impasto patches of white paint for clouds. Compared to the illustration the painting features less anecdote, as broad areas of pure color replace story telling with visual delight. But Michel’s illustration does have narrative: the wide-eyed boy looks admiringly at the spirited girl and issues of gender are raised by the image, as they often were in Michel’s illustrations for the “Parent and Child” column.

The treatment of gender in her hundreds of illustrations raises intriguing questions, complicated by the fact that the drawings were made in dialogue with the texts of the articles. For example “Time Out for Hobbies” features four scenes; a boy plays with toy airplanes, another with a chemistry set, while a girl organizes shells, a scientific activity, and the second girl works printing photographs. But in the essay that accompanies the illustration in the Times it is a boy who practices photography. Michel changed the gender in her illustration as her girls pursue pre-professional activities that have nothing to do with being house wives. (8)

A horse dominates the 1955 painting, Harness Racing, against a typically simplified space, with a richly varied range of greens defining the land, hills and sky. In the center the galloping horse drags a small human figure whose pink shirt contributes a sharp note of contrasting color. The horse itself is a fine demonstration of Michel’s drawing talent: foreshortened, its head turns to its left while its body moves right, all encapsulated in one complex irregular shape, painted an unrealistic pale blue gray that indicates it is art, not illustration. Another horse, in At a Gallop, with its tiny rider perched on it as it races around a dark ring, recalls the haunting Death on a Pale Horse by Albert Pinkham Ryder, an artist greatly admired by the Averys.9 In Michel’s version the glowing colors of the landscape, surmounted by a pale orange sky, set off the dark environment of the racing horse and rider. The loneliness of the solitary figure evokes an existential mood uncharacteristic of the artist, but also hinted at in her Woman by the Lake with its lone woman isolated before nature, reminiscent of 19th century Romantic imagery. These two paintings stray from the sense of well-being and the harmony of everyday existence that characterize the Avery aesthetic, suggesting again that Sally Michel’s artistic achievement is deeper than presently recognized.

I thank Deedee Wigmore for asking me to write this essay, Emily Lenz for her capable and encouraging assistance, Jeanette McDonald for her indispensable help with my research, Melissa De Medeiros for her gracious assistance, and March Avery Cavanaugh for her generosity with her Sally Michel materials, as well as Sean A. Cavanaugh. Informative interviews with Sally Michel Avery include: Louis Sheaffer for the Columbia Center for Oral History, December 19 and 26, 1978, January 2 and February 9, 1979; Tom Wolf for the Archives of American Art, February 19, 1982, and Nancy Accord for the Fresno Art Museum, December 2 and 3, 1989. The quote is from the Accord interview, p. 16.

As Barbara Haskell described it, “The metamorphosis of representational elements into flat, interlocking shapes of homogenous color formed the basis of his mature work.” Milton Avery, Whitney Museum of American Art in association with Harper Row Publishers, New York, 1982, p. 49.

Schaeffer interview, p. 9.

Accord interview, p. 1.

Accord interview, p. 2.

The drawing appeared in “Counsel for the Troubled Family,” New York Times Magazine, June 30, 1957, p.167.

The drawing appeared in Playtime with Music, lyrics and text by Marion Abeson, music and arrangements by Charity Bailey, illustrations by Sally Michel, Liveright Publishing Corporation, New York, 1952, np.

“Time Out for Hobbies” New York Times, June 2, 1957, p. 225.

Schaeffer interview, p. 9.

[ TOP ]