Sept 14- Nov 22, 2017

Essay | Selected Exhibitions and Museum Collections | New York Times Review

Essay by Tom Wolf, Professor of Art History, Bard College

When asked, two years after the death of her husband, whether she should be referred to as “Sally Michel or Mrs. Milton Avery”, she replied, “They’re both one and the same.”* Sally Michel married the painter Milton Avery, seventeen years older than she, in 1926 and thereafter her life was intertwined with his. She was a young artist, totally dedicated to painting. In him she found someone equally committed to making art, her life companion until his death in 1965. He had an approach to painting that she found valid and would practice for the rest of her career: “We actually had a lot of the same ideas about art even before we met.…” What attracted him when they met in Gloucester was that, like him, she was up early each morning, going outside with her art materials to make oil paintings.

Art historian Robert Hobbs described the Avery marriage as “a relationship with few parallels in the history of art.” While her commitment to making her own art never wavered, Michel had no problem putting him in the foreground, working to support him financially and promoting his art, while steadily practicing her own painting, usually side by side with him. “I wanted all the spotlight to be on Milton.” “And I really thought Milton’s work was really so much more important than mine.” She did commercial artwork for twenty years so he could devote all his time to painting. In large part the uniqueness of their relationship lay in the fact that she was genuinely happy helping him to be a full-time artist while she made her art in his shadow. She worked on commercial illustration jobs at home, so they were almost constantly together. The day before their daughter was born she made a drawing for Bamberger’s department store that was picked up from the hospital. Avery was not a prima donna—he helped around the house, washing diapers and doing dishes and some of the cooking. She wrote his letters; “and... all those statements that were made for magazines and when they asked for credos, I just wrote up something. . . But actually, I was saying what I knew he thought.” As artist and writer Frederick Wight observed, “Sally Avery speaks for her husband, bridging over his shyness; or rather he speaks through her, since it is obvious that she says what he needs said.” They fit together like two interlocking color areas in one of their paintings, complementing and strengthening each other.

Their art developed together. Curator Barbara Haskell has pointed out that when Avery moved to New York to pursue Michel he had not yet experienced the modernist art that had burst out in Europe and was making an impact in the New York art world. His style had developed out of late 19th century American prototypes. After he relocated and they were married (as Michel said, “He chased me until I caught him”) he started painting with flatter, more simplified shapes. When Avery and Michel met in Gloucester they were painting outside, but once they settled in New York they preferred to sketch on paper outdoors and then develop their sketches into oil paintings on canvas at home.

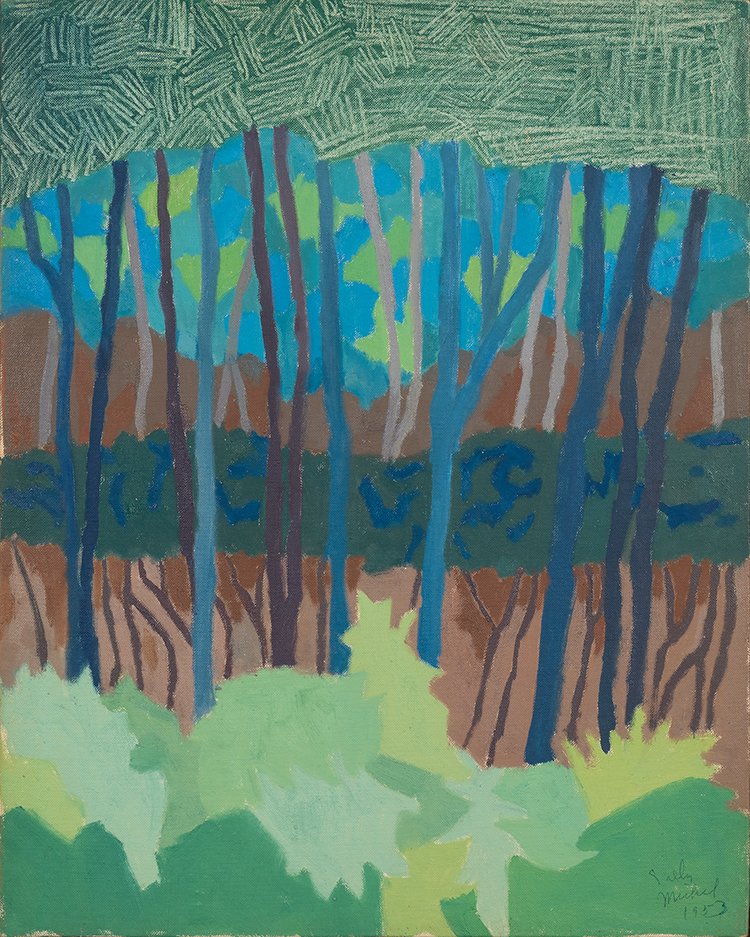

Most of Michel’s paintings in this exhibition are landscapes, a traditional genre both Avery and Michel often practiced, especially during their summer travels. The earliest here date from 1953, when Avery’s art was gradually selling better and the couple was beginning to see the end of two decades of living frugally. Red Landscape and Birch, both from 1953, modest sized, vertical paintings centered on trees, typify Michel’s style at this point. The two paintings share an avoidance of realist detail, and a flattening out of landscape space, but they are distinctly different in color, with Birch featuring tans and a rich range of cool blues and blue greys, while Red Landscape ranges from muted reds to hotter oranges with only a few dots of green to ignite the scene through contrast. The emphasis on radiant color parallels the Averys’ friend, Mark Rothko’s paintings from the same years, with the difference that the Averys always kept a connection to the real world in their imagery and never ventured into total abstraction.

When she painted these two tree paintings Michel was supporting her husband with commercial jobs. Her mainstay was illustrating a weekly parenting column for the New York Times. She did this for twenty years; once she retired in 1960 the column was cancelled. These black and white illustrations demonstrate another side of her talent, the drawing skill that drew her to being an artist when she was a child. A scene of a youthful party features eighteen figures, a crowd never seen in her paintings, where broad, flat forms that are vehicles for color are the rule. The people are economically characterized and each individual activity is precisely captured. In the bottom left corner a girl draws the lettering for a party announcement, the one person involved in drawing—an alter-ego common in these drawings, which often feature images of girls making art (and often, as here, resembling her daughter, March). The Averys were aloof from politics, interested only in their painting. Milton never voted, and although they lived through the Depression and World War II there are few traces of these historic events in their painting. There are a few exceptions in Michel’s drawings for the Times, when the text in the article called for it—for example a drawing from 1941 where a boy plays with toy soldiers on the floor while his parents both anxiously read newspapers and the radio blares, “Battles, Italy, Greece, WAR.” In these drawings, Michel masterfully captured psychological and narrative moments, which makes clear that she deliberately rejected these qualities in her paintings for the sake of form and color.

It is well known that in the 1930s and 1940s Avery was an inspiring figure for a group of ambitious younger artists who would become famous as Abstract Expressionist painters: Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, and Barnett Newman. They admired his dedication to his art and his individualistic style, which built on developments of European modernism against the prevailing trends in American painting. They visited constantly and took vacations together. Like Michel, the wives of the younger artists supported their husbands, though they did not share her absolute commitment to painting at the same time. “No, I don’t think any of the women were as dedicated as I was to art. I was really dedicated to art and they were dedicated to their men, and if they painted, okay, but art was really like the Holy Grail.” Unlike Avery, who came from a Protestant family, the younger artists were Jewish, as was Michel. Her family was observant and not pleased that she married a non-Jew. Once she married she was no longer invited to their Sabbath meals, though they gradually came to accept Avery. After he died in 1965 Michel began to travel internationally, not only to Europe but also twice to Africa, and she also made five trips to Jerusalem, suggesting that she had an identification with her Jewish background despite her nonobservant lifestyle.

“I tell you, when I think of the fate of women it just wrings my heart. . . . It’s terrible,” Michel said in an interview with Nancy Acord where she told the story of her parents. Her father came to the United States from Poland; after some years he decided he wanted to marry and returned to Poland to find a wife. He settled on Michel’s mother who agreed to marry him on the condition that they remain in Poland. He assented, they married, and the next day he put her on the boat to the United States. Several years later, after they had two of their eventual five surviving children and his finances were bad, he sent her back to Poland to live with his family for a year and a half before calling her back to the U.S. Michel concluded this part of the interview stating, “I’m not a feminist but I’m a humanist.” Like some other women artists of the time, such as Helen Frankenthaler, she claimed, “Personally, I wish there wasn’t so much emphasis on women. I think there should be more emphasis on good work and bad work. To be judged not by whether you’re a woman or not but by whether you’re a good artist or not.” She also felt, “I think my work right now is naturally influenced by Milton. I couldn’t help it having lived with him so long. I hope it’s more feminine because I’m a female.” Today “feminine” is a loaded term, but perhaps she was referring to the delicacy plus the sophisticated use of pattern found in her commercial drawings and made blunter in some of her paintings, such as Ida, a portrait of family friend Ida Baumbach (the grandmother of film director Noah Baumbach). Lost in thought or sleeping, Ida is surrounded by dazzling colors while the grid of the table plays a visual game, making a pattern of multicolored diamonds from the orange of her dress, grey from the background, and a sly bit of pink from her leg.

Michel’s practice of travelling extensively began two months after Avery passed away, when he had an exhibition in London and the dealers persuaded her to come. She was economically independent, thanks to Avery’s success in the art market in his last years, and free to pursue her own art full time. She bought a house in Bearsville, outside of Woodstock, and its serene surroundings became the subject of many of her works. A photo documents her practice of sketching outdoors, the subject her grandson and friends relaxing on the lawn in Bearsville, a casual gathering of the sort that inspired paintings like Bill and Friends. Her paintings became larger now that she had more space to paint and was not doing commercial work any more, and they are thinly and quickly painted, giving a sense of watercolor-like luminosity and a casual spontaneity. She had a horror of paintings that looked labored: “I think it just ruins it. I have worked on paintings like that for a long time but I usually throw them away in the end. I mean all the life and all the joy goes out of them.”

It would seem that the grace that characterized Michel’s art and her life had its source in her positive and upbeat personality: “I was always an optimist.” “Have you ever been sad a day in your life, Sally?” interviewer Acord asked her somewhat incredulously. Of course she had been but her overall affirmative attitude was manifested in her art, like Studio View (1977), a rare urban scene, gridded like a Mondrian, but with an array of thinly brushed pastel colors.

Her Bearsville house afforded Michel a variety of landscape subjects: it is on a hill, surrounded by trees, above a pasture where cows often grazed before distant mountains. In Last Snow (1984), one of her late landscapes, she transformed the geography before her into areas of radiant, unrealistic color. A sketch for the painting exists, where she roughed out the basic composition and included some color notes. The notes indicate a yellow ground plane with tan accents; these she brightened into pink in the actual painting. She added a pale brown sky, a duller version of the bright yellow below, to create a field of warm yellows punctuated by darker hues representing trees and a mountain.

While Michel often denied any narrative interpretations of paintings, saying of Avery’s “they have no literary content,” on another occasion she said, “Every painting is an adventure. . . .You’re really delving into all your memories and things that have happened to you.” A Bearsville painting, Orange Sky (1977), where three cows hit individual color notes against a pale green pasture, evokes the summer of 1930 with her husband in Collinsville, Connecticut: “That whole summer we spent wandering after cows and making sketches. One farmer had these cows that used to travel about a mile for pasture, so we’d walk in back of them sketching, picking up apples and pears to eat.” The mountains and bands of foliage undulate peacefully under the livid orange sky, in a painting that affirms the present while also recalling an idyllic past.

“I think a painting should look as if it just happened. It should be a miracle.” “I really feel sorry for people that can’t paint because it’s so much fun to paint and it makes every day an adventure.”

NOTES

*This essay follows “Sally Michel: Working Artist” which I wrote for the Sally Michel: Rhythms of Light and Color catalogue of Michel’s November 2015 exhibition at D. Wigmore Fine Art. There is necessarily some repetition but I have tried to cover new ground. Instead of footnoting my sources I will cite them below. Because she lived to age 100 and was an open person she gave several lengthy interviews which have been among my main sources: interview with Dorothy Gees Seckler, November 3, 1967, Archives of American Art; four-part interview with Louis Sheaffer, December 1978-February 1979, Columbia Center for Oral History; interview with Tom Wolf, February 19 and March 19, 1982, Archives of American Art; and interview with Nancy Acord, Fresno Art Museum, December 2 and 3, 1989. All the quotations from Sally Michel in my text come from these interviews. Other sources cited are: Robert Hobbs, “Sally Michel: The Other Avery,” Woman’s Art Journal, Fall 1987/Winter 1988, 5; Frederick S. Wight, Milton Avery, Baltimore Museum of Art, 1952, 9; Barbara Haskell, Milton Avery, Whitney Museum of American Art, 1982, 40f. Michel’s “WAR” drawing illustrates the “Parent and Child” column, “Mental Hygiene” by Catherine MacKenzie, The New York Times (magazine section), Sunday, February 9, 1941, 22. In writing this essay I am grateful for the encouragement and assistance of Deedee Wigmore, Emily Lenz, March Avery Cavanaugh, Sean A. Cavanaugh and Melissa De Medeiros at The Milton and Sally Avery Arts Foundation, and at Bard College, Jeanette McDonald.

[ TOP ]