Essay by Emily Lenz

Charles Green Shaw (1892-1974) contributed to the development of American abstraction in the 1930s and 1940s through his own work and his involvement in three important New York art circles. He is most associated with the Park Avenue Cubists, a group of wealthy artists who provided connections between New York and Paris during the Great Depression. Shaw was in fact not as wealthy as his fellow Park Avenue Cubists A.E. Gallatin (1881-1952), George L.K. Morris (1905-1975), and Suzy Frelinghuysen (1911-1988). This freed him from social and family responsibilities, allowing Shaw to spend more time in his studio and develop friendships with a broad group of abstract artists. Shaw was a founding member of the American Abstract Artists (AAA) group, established in 1936 when forty artists banded together to promote abstraction through annual exhibitions open to the public. In the AAA’s early years, Shaw worked to find gallery space and sponsors for their exhibitions. Shaw was also part of the circle around Hilla Rebay, curator of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (now the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum). When the museum opened in 1939, Rebay included Shaw in a number of group exhibitions and gave Shaw solo exhibitions in 1940 and 1941. Additionally Shaw advanced abstraction through his advisory board position at the Museum of Modern Art (1936-1941) and his illustrated children’s books intended to introduce abstraction to younger generations.

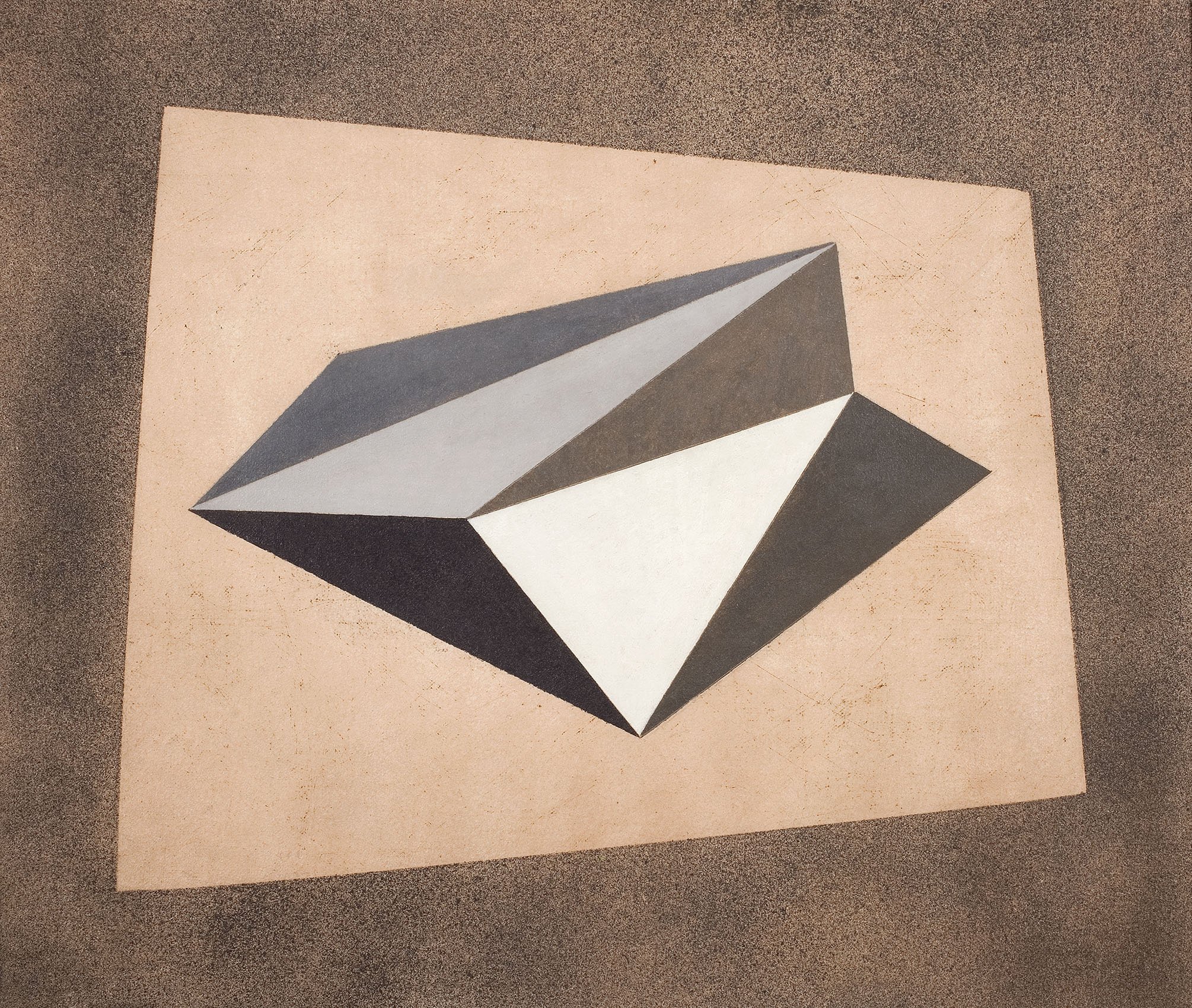

Many of Charles Green Shaw’s choices in early life laid the foundation for his later interest in abstraction. He took a general science degree at Yale University that mixed science, math, and the liberal arts, graduating in 1914. He began a graduate degree in Architecture at Columbia University that was cut short when Shaw enlisted in World War I, serving in the Army’s Air Service. His keen sense of observation was first applied to journalism, writing for The New Yorker, Smart Set, and Vanity Fair through the 1920s. Shaw began art lessons in 1926, studying briefly with Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975) at the Art Students League then more extensively with George Luks (1867-1933). Shaw set out for Paris in 1929 and stayed in Europe through 1933. There, Shaw’s eyes were opened to abstraction through the Cubist work of Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Georges Braque (1882-1963), and Juan Gris (1887-1927). From 1930 to 1935, Shaw worked through Cubism to find an American version that was simplified and more geometric. This is seen in Three Pear Composition, 1935 which has a Cubist still life composition and faux bois elements, but Shaw treats the pears as biomorphic forms and replaces the tabletop with a mass of projecting geometric shapes.

In the early 1930s, Shaw worked alone developing his abstract vocabulary. When he returned to New York in 1933, he knew no other abstract artists working in the city. That changed in the spring of 1935 when Shaw met A. E. Gallatin (1881-1952), a wealthy collector who opened his collection of European Modernism to the public as The Gallery of Living Art on NYU campus. The gallery was the earliest public institution to show abstraction. After Gallatin’s first visit to Shaw’s studio, he returned with George L.K. Morris (1905-1975), who acted as curator for the Gallery of Living Art. The two purchased a painting for the gallery’s collection and selected eight of Shaw’s paintings for a solo exhibition, breaking the museum’s protocol of group exhibitions only. In the summer of 1935, Shaw traveled to Paris with Gallatin and Morris who provided introductions to many great painters. Conversant in both French and German, Shaw had no problem communicating with the array of European artists working in Paris at the time. In 1936 in response to Alfred Barr excluding Americans from his two major exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art and Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism, Gallatin, Morris, and Shaw organized an exhibition called Five Contemporary American Concretionists at the Reinhardt Gallery that included Shaw, Morris, John Ferren (1905-1970), Alexander Calder (1898-1976), and Charles Biederman (1906-2004). The exhibition traveled to Paris at the Galerie Pierre and to London at the Mayor Gallery with Gallatin replacing Calder as the fifth artist.

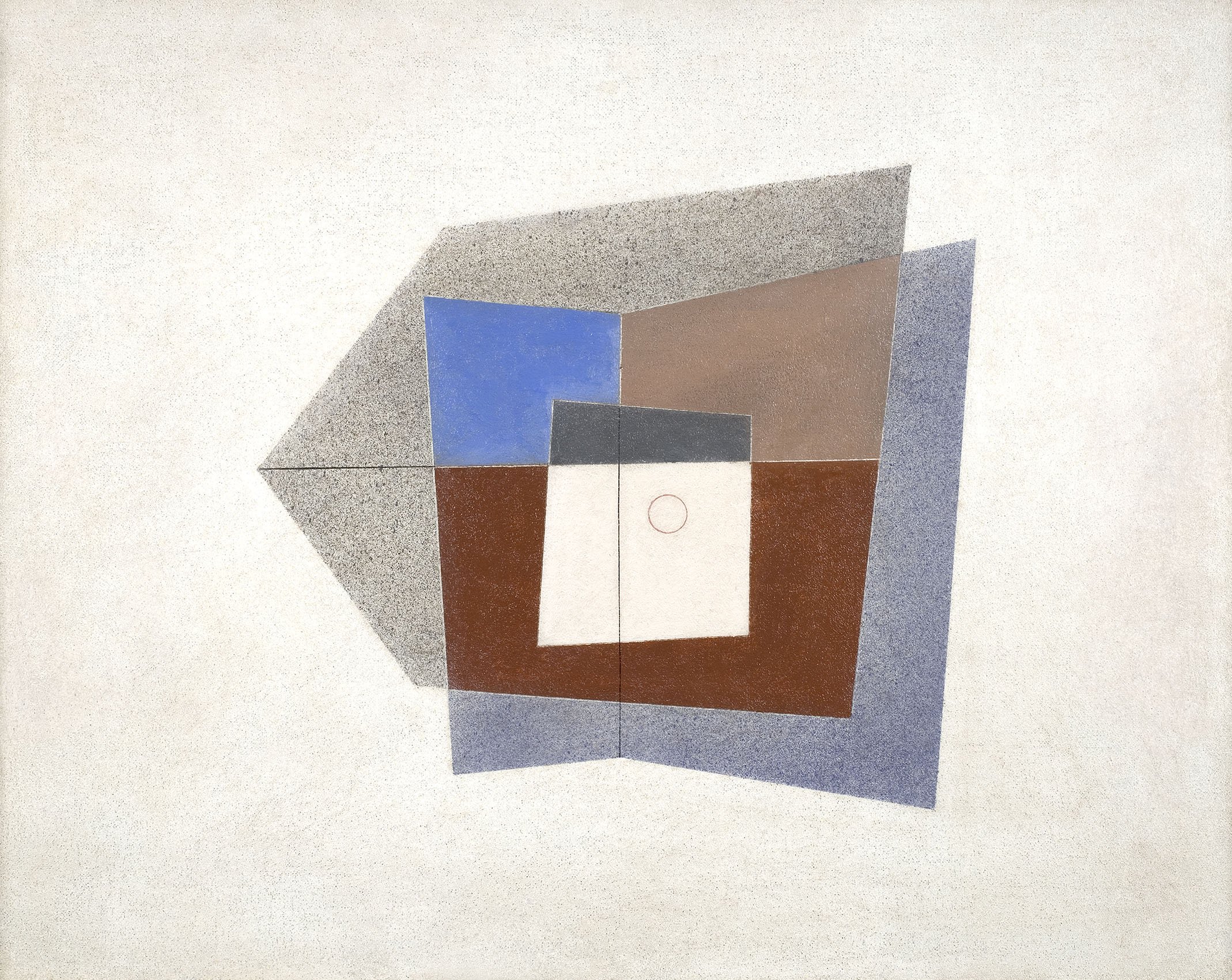

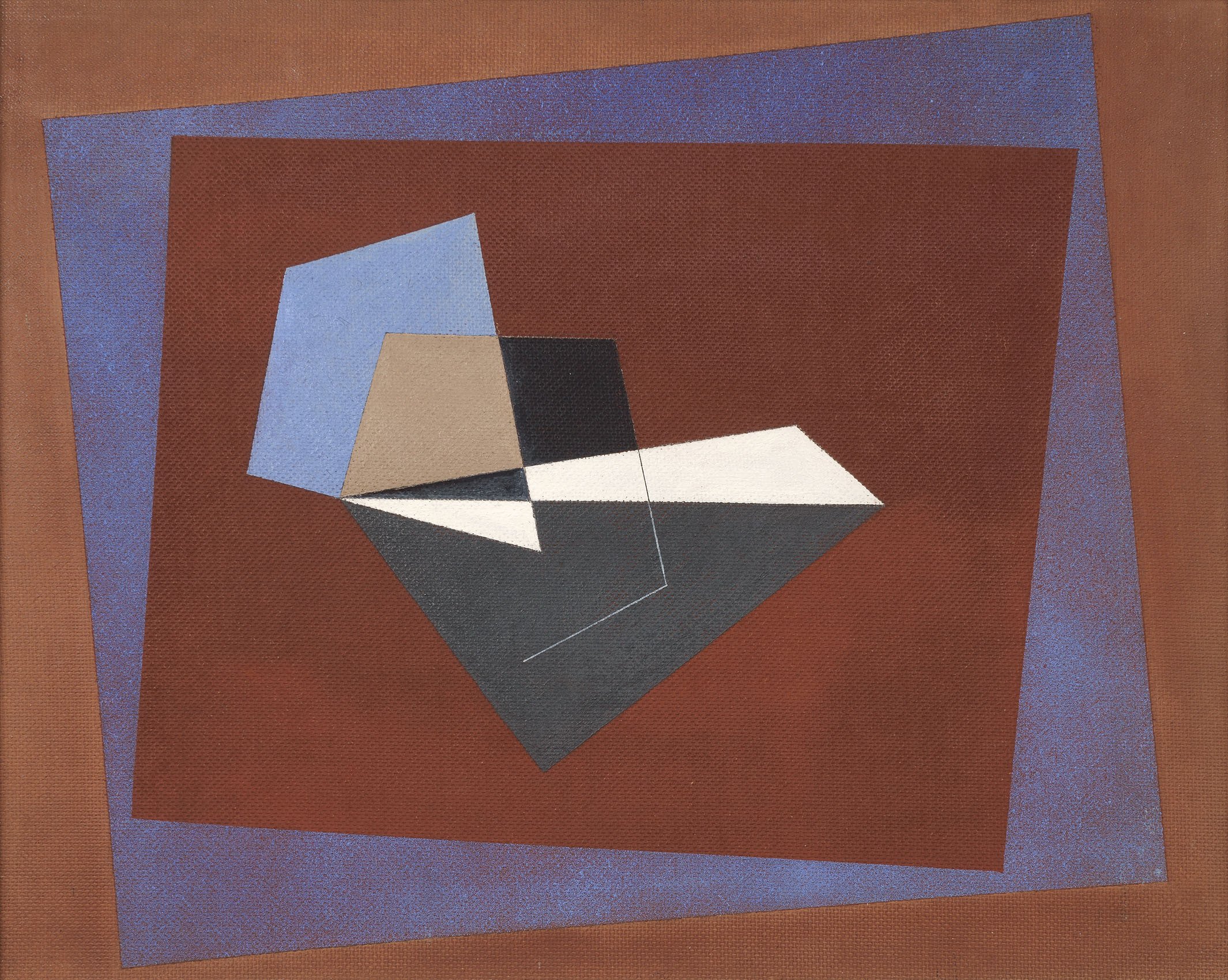

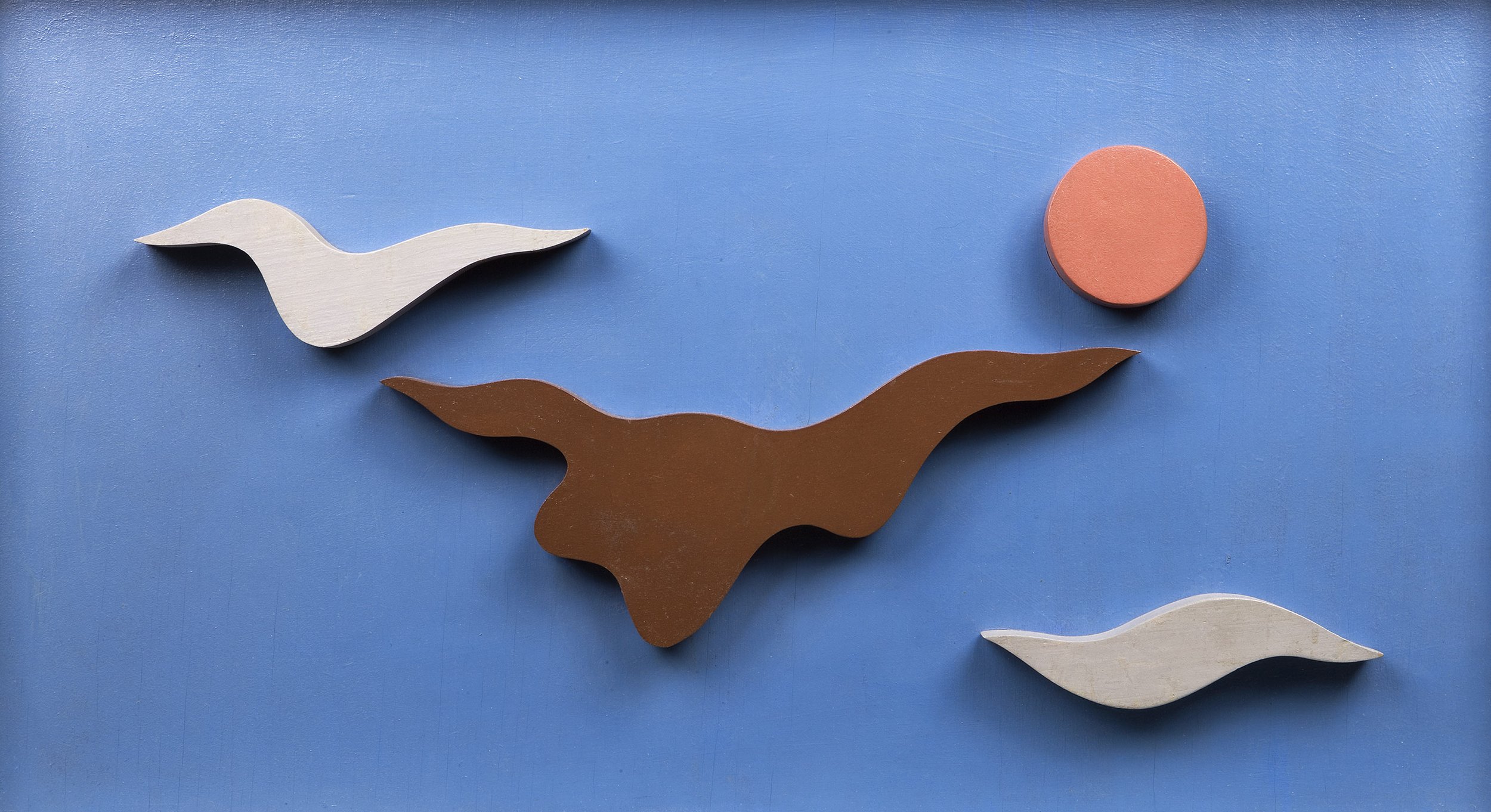

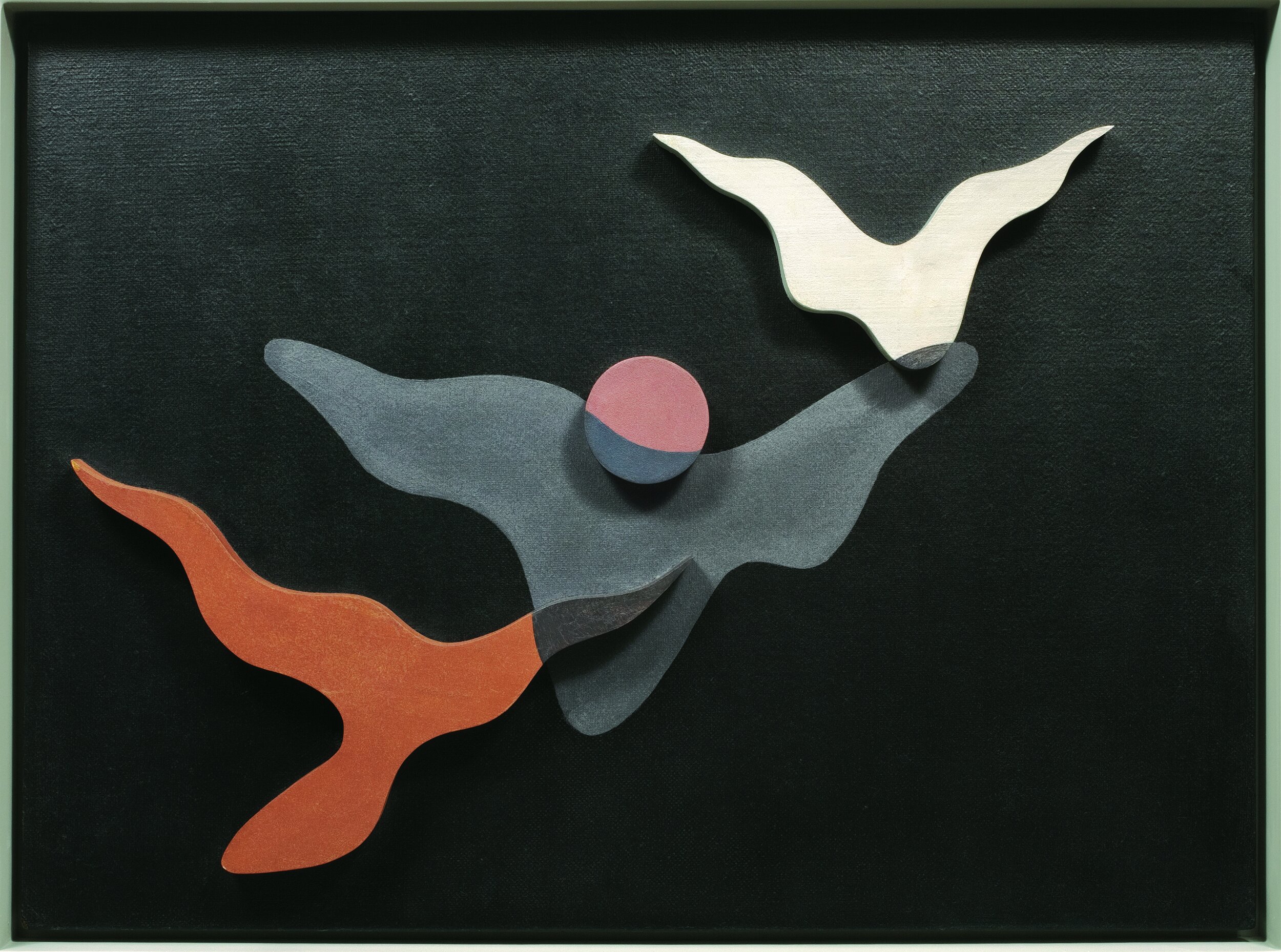

The exhibition at D. Wigmore considers the evolution of Charles Green Shaw’s style from the early 1930s through the mid-1940s as Shaw works his way through Cubism and Surrealism to find his own American voice. The dynamic energy of New York became Shaw’s source for an American abstraction. Shaw noted the broken patterns of the modern city where rhythmic movement was seen in every direction, from the geometry of sidewalks repaired and repaved to an ever changing skyline as more skyscrapers were built. Shaw created abstractions based on his observations of the city. Shaw first evokes the city’s sky line with his Plastic Polygons constructions as seen in Day and Night Polygon, 1936 then in more nuanced ways in paintings of pure geometry. Shaw’s evolution from the 1930s to the 1940s can be demonstrated with comparisons of paintings from the D. Wigmore exhibition.

Shaw’s use of Cubism and his evolution towards pure geometry is shown when Chrysalis, 1935 and Divided Planes, 1943 are placed side-by-side. In Chrysalis, one sees Shaw’s debt to Picasso as a teacher. The sculptural form suggests a Picasso-like bust floating against a blue ground. Shaw rounds the forms with modeling to convey depth and volume. A black semi-circle stands in for an eye, suggesting both a woman’s profile and a point of access into the overall form. With Chrysalis next to Divided Planes, one sees not only a shared palette but also how Shaw flattened the biomorphic forms from Chrysalis into pure geometry in Divided Planes. Shaw creates depth in Divided Planes through layering of planes, achieved through a mix of stippling to imply transparency and overlapping of single colors. In place of an eye, Shaw uses a three-sided line to imply an opening into the composition of Divided Planes. The comparison of the two demonstrates how Shaw moved away from French abstraction into a streamlined geometry that may suggest horizons and vistas but is strictly non-objective.

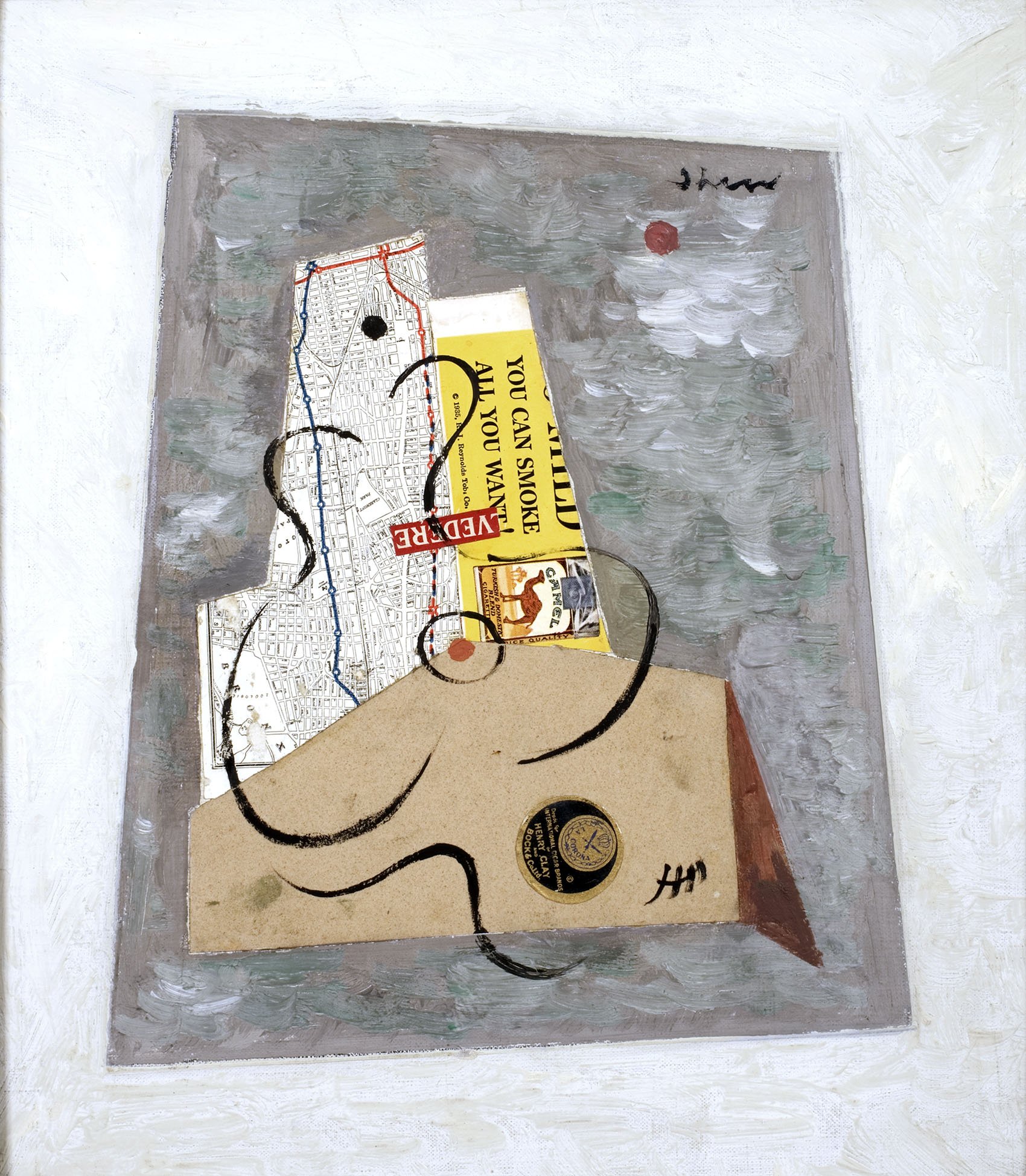

Shaw’s distinct abstract voice has a playful side and an interest in breaking forms down into geometric shapes. This can been seen in a comparison of the drawing Self-Portrait, 1935 and the painting Refraction, 1940. In the 1935 drawing, Shaw depicts himself in hat, glasses, and tie with a spare use of line and shapes. The verticality of the portrait connects to his first Manhattan skyline paintings. The thick black band on his hat gives solidity to the composition and the elegant arrangement of circles and triangles in place of his eyes and nose its focal point. Already we see Shaw’s economy of line and paring down of the human figure into an arrangement of geometric shapes. Refraction, 1940 is a different type of portrait with the letters of Shaw’s last name appearing in the composition. The coiled black lines convey the springing motion that seems to have circulated the artist’s name around the canvas. In Refraction, Shaw has found a personal American abstraction- direct, streamlined, and witty. Refraction is forward looking with a proto-Pop sensibility. Its mixture of punchy design, self-reference, and primary colors are all elements that appear in Jasper Johns’s work two decades later.

In a 1968 oral history for the Archives of American Art, Shaw spoke of solidity, impact, balance, and tension as defining principles of his abstractions. Throughout his career, Shaw’s paintings reflect modern awareness of space, speed, and a shift from classic symmetry to dynamic movement in order to capture the energy of Twentieth Century life. As a result, Shaw achieved a distinctly American abstraction.

[Top]

Modernism 1913-1950 | Realism of the 1930s and 1940s | Abstraction of the 1930s and 1940s | Post-War | Selected Biographies