June 5 - August 30, 2019

Read essay here. | Some works may still be available, please contact the gallery at 212-581-1657

Essay by Deedee Wigmore

Our exhibition hopes to tell how America went abstract with a particular focus on the use of collage by artists to develop purely geometric compositions. The history of the American experience with abstraction begins with the 1913 Armory Show, which created the first public awareness of European Modernism and its abstract artists. The next major event was the founding of the American Abstract Artists group in 1936, when artists practicing in New York banded together to push for broader acceptance of their style.

Between 1913 and 1936, a significant number of American artists traveled to Europe. Some lived there for extended periods, including John Ferren, Balcomb and Gertrude Greene, A. E. Gallatin, Carl Holty, George L. K. Morris, Charles Green Shaw, and Jean Xceron. Josef Albers, Werner Drewes, Ilya Bolotowsky, and Esphyr Slobodkina were recent immigrants from Germany and Russia. Periodicals like Cahiers d’Art and exhibitions of European modernists by Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery, Katherine Dreier and Marcel Duchamp’s Société Anonyme, and A.E. Gallatin’s Gallery of Living Art were available to artists who did not leave America. The American Abstract Artists group formed at a time of heightened social consciousness when art was expected to deliver answers to social concerns and deliver it in an accessible realist language.

How to build an audience was a problem the diverse group of artists who founded American Abstract Artists faced. They began to meet informally in 1936 in various studios in New York as a way to become familiar with each other’s work. The group decided the only way to create an audience for abstract art was to rent a space where it could be shown. The group’s first annual was held in April of 1937 with 100 paintings executed by 39 artists. The exhibition ran for two weeks at the Squibb Building on Fifth Avenue and attracted 1,500 curious visitors, but had little critical success. Their next exhibition, held in 1938, drew 7,000 visitors and gained some reviews. Portions of the exhibition traveled to cities throughout the country, including Seattle, San Francisco, Kansas City, and Milwaukee. Our exhibition offers paintings by early members of the American Abstract Artists: Bolotowsky, Drewes, Gallatin, Balcomb Greene, Holty, Morris, Shaw, and Xceron, along with collages by Bolotowsky, the Greenes, and Slobodkina.

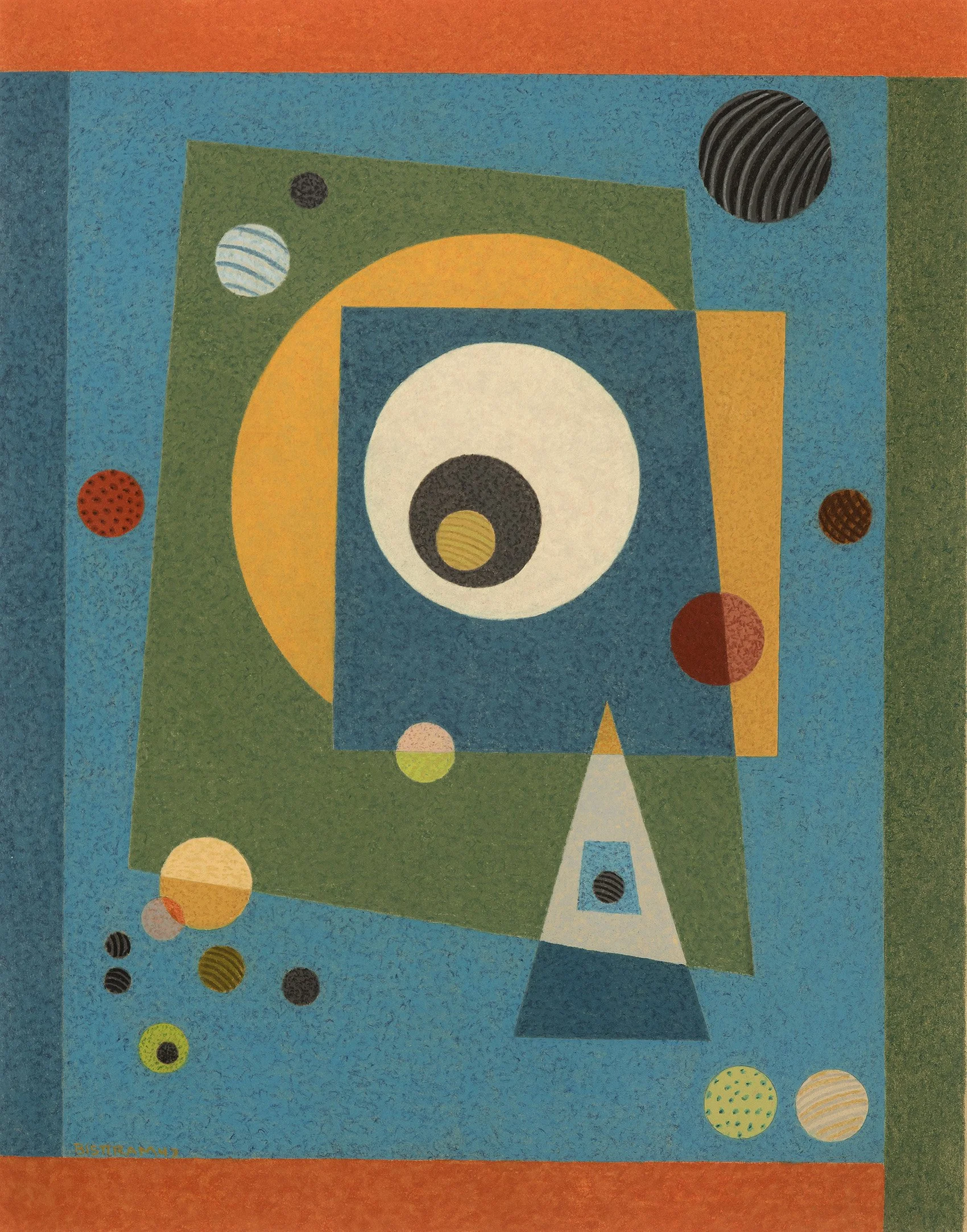

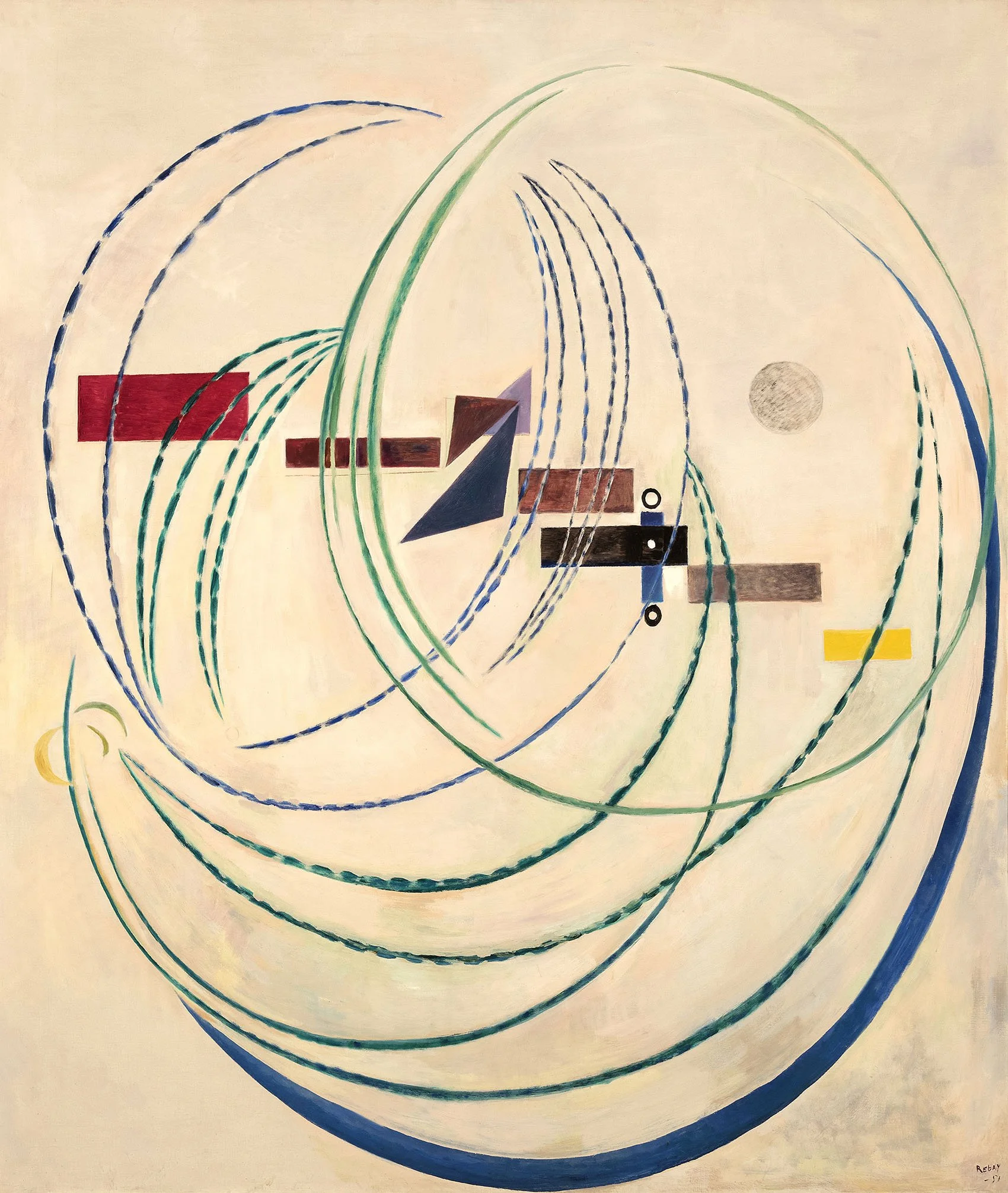

Many of the American Abstract Artists members had additional opportunities for exhibition with the founding of Hilla Rebay’s Museum of Non-Objective Painting. Rebay was Solomon R. Guggenheim’s art advisor and persuaded him to acquire non-objective art and make it available to the public. In 1939 The Museum of Non-Objective Painting opened in a showroom at 24 East 54th Street, exhibiting both European and American artists working in an abstract style. AAA members Irene Rice Pereira and Balcomb and Gertrude Greene were the subject of the museum’s first loan exhibition in 1940 (January 3 – February 14). Jean Xceron was in the second loan exhibition and Charles Green Shaw had solo exhibitions in 1940 and 1941. The Museum of Non-Objective Painting sought out artists inspired by Kandinsky’s writings on the spiritual in art, which led the New Mexico Transcendental Painting Group to exhibit there in 1940. Our exhibition includes Circles in Motion, 1943 by Transcendental painter Emil Bisttram, three examples by Raymond Jonson, and Composition #112, 1938 by Stuart Walker. Werner Drewes was included in an exhibition of artists inspired by Kandinsky in 1941 and is represented in our exhibition with Loose Contact, 1938 and Yonder the Tracks, 1943. Hilla Rebay, while serving as the director from 1939-1952, exhibited her own work regularly at the museum, as well as supporting other women from across the country. Chicago Bauhaus artist Marguerite Hohenberg and New Mexico painter Dorothy Morang both exhibited at the Museum in 1944 and are represented in our exhibition. For Rebay, our exhibition includes four untitled collages and an oil titled Rondo #1, Charm of Existence. Rebay was instrumental in selecting Frank Lloyd Wright as the architect for the museum’s final home, which would become the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum after its patron’s death. Rebay had significant dealers in New York (Wildenstein) and Paris (Bernheim-Jeune) while she was director and after leaving her position in 1952, Rebay exhibited with French and Company in New York.

Perhaps the largest task for the pioneers of American abstraction was to figure out how to make a successful abstract painting. Looking at paintings in our exhibition, one is struck by evidence of collage use by Ilya Bolotowsky in Geometry on Green, 1937 supported by collages #2 and #5. In Balcomb Greene’s Black Rectangle, 1937 and Memory Forms, 1939, one suspects the artist designed paintings with collage, which is supported by collages 38C7 and 37-1 found in our exhibition. Artists thought of collage as designing with scissors, allowing the artist to build a composition in a quick and inexpensive way based on look and feel before thoughts censored out creativity. If a shape looked wrong the artist could peel it off to make a revision or paste another shape on top of it. Cut-outs in a variety of shapes could be moved around to try different placements of line and form. Carl Holty’s Geometric Abstraction, 1940 has the feel of cut-outs being used with the layering of shapes on top of each other. The collage process allowed an artist to welcome interesting textures that might develop through the accidental use of a handy piece of cloth, paper, label, or foil. Movement and rhythm could be created by variations of light and dark shapes and also by alternation of flatness and depth. A collage by Esphyr Slobodkina titled Annual, 1939 fits this description. Collage shapes, unlike the drawn line, include form and volume in their very nature. The background paper acts as the picture plane, forcing the pasted collage elements to thrust into space. The starts and stops of line and color using collage resulted in a new approach to spatial interplay. The importance of collage can be seen in Piet Mondrian’s last painting, Victory Boogie Woogie, 1944, left unfinished in his New York studio. In the painting Mondrian used collage to develop his severe, rectilinear abstractions by placing colored tapes on plain canvases to study the space relations, rhythms, and precise equilibrium of the tapes. Mondrian constantly shifted and rearranged the tapes, only once satisfied did he paint actual lines in place of each tape. This was documented by AAA members who covered the rent of Mondrian’s studio for some months after his death so other abstract artists could study Mondrian’s use of collage. This adaptability explains the strong feeling of collage use in the paintings in our exhibition by diverse groups of abstract artists.

[ TOP ]

Modernism 1913-1950 | Realism of the 1930s and 1940s | Abstraction of the 1930s and 1940s | Post-War | Selected Biographies