Feb 27 - May 3, 2019

Read essay here. | Some works may still be available, please contact the gallery at 212-581-1657

Essay by Emily Lenz

The shaped canvas was explored by artists of the 1960s in diverse styles including Hard-Edge, Color Field, Op, Pop, and Minimalism. The architectural structure of shaped canvases moved painting beyond the traditional rectangle that replicates the viewer’s field of vision. Lawrence Alloway brought attention to this movement in his Guggenheim Museum exhibition The Shaped Canvas (December 1964 - January 1965), which included Paul Feeley, Sven Lukin, Richard Smith, Frank Stella, and Neil Williams. In January of 1965, Frank Stella, Henry Geldzahler, and Barbara Rose organized the exhibition Shape and Structure at Tibor de Nagy Gallery, which included shaped canvases by Stella and Williams, as well as Charles Hinman, Will Insley, and Larry Bell, alongside three-dimensional works by Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Carl Andre, and Robert Murray. The Tibor de Nagy exhibition presented a group of artists investigating the relationship of a work’s internal structure and its bounding shape. It also showed the division between the Minimalists whose interest was the materials and the shaped canvas makers whose interest was color and accepted some level of pictorialism as a result. Our exhibition focuses on the Hard-Edge artists and their creativity in finding unified and balanced compositions within new forms.

In the early 1960s, Clement Greenberg’s call for painting to be flat still dominated. In Frank Stella’s early shaped canvases, the paint was stained into the canvas, staying within Greenberg’s doctrine. The physical depth in the shaped paintings of Sven Lukin and Charles Hinman broke with “the rules.” Lukin and Hinman set the stage for younger artists like Elizabeth Murray to redefine painting with her 1970s shaped canvases that mixed abstraction and representation, geometry and biomorphism. The shaped canvas movement paved the way for artists of the 1970s to re-evaluate what painting could be and in due course opened the door to the diverse art produced today.

1930s PRECEDENTS

In the 20th century, abstraction freed painting to be about the arrangement of shapes and colors. Without a natural order to follow, artists inevitably asked why must the canvas be a rectangle? At the same time, the challenge of developing an abstract language led many artists to use collage in their preparatory work. Paper cut-outs allowed for quick adjustments to compositions and led several American pioneers of abstraction to consider how this additive process could apply to their painting, resulting in the development of constructions and reliefs. Charles Biederman, Gertrude Greene, Charles Green Shaw, and Irene Rice Pereira were the primary American artists to work in painted constructions or reliefs in the 1930s, setting the precedent for the shaped canvas of the 1960s.

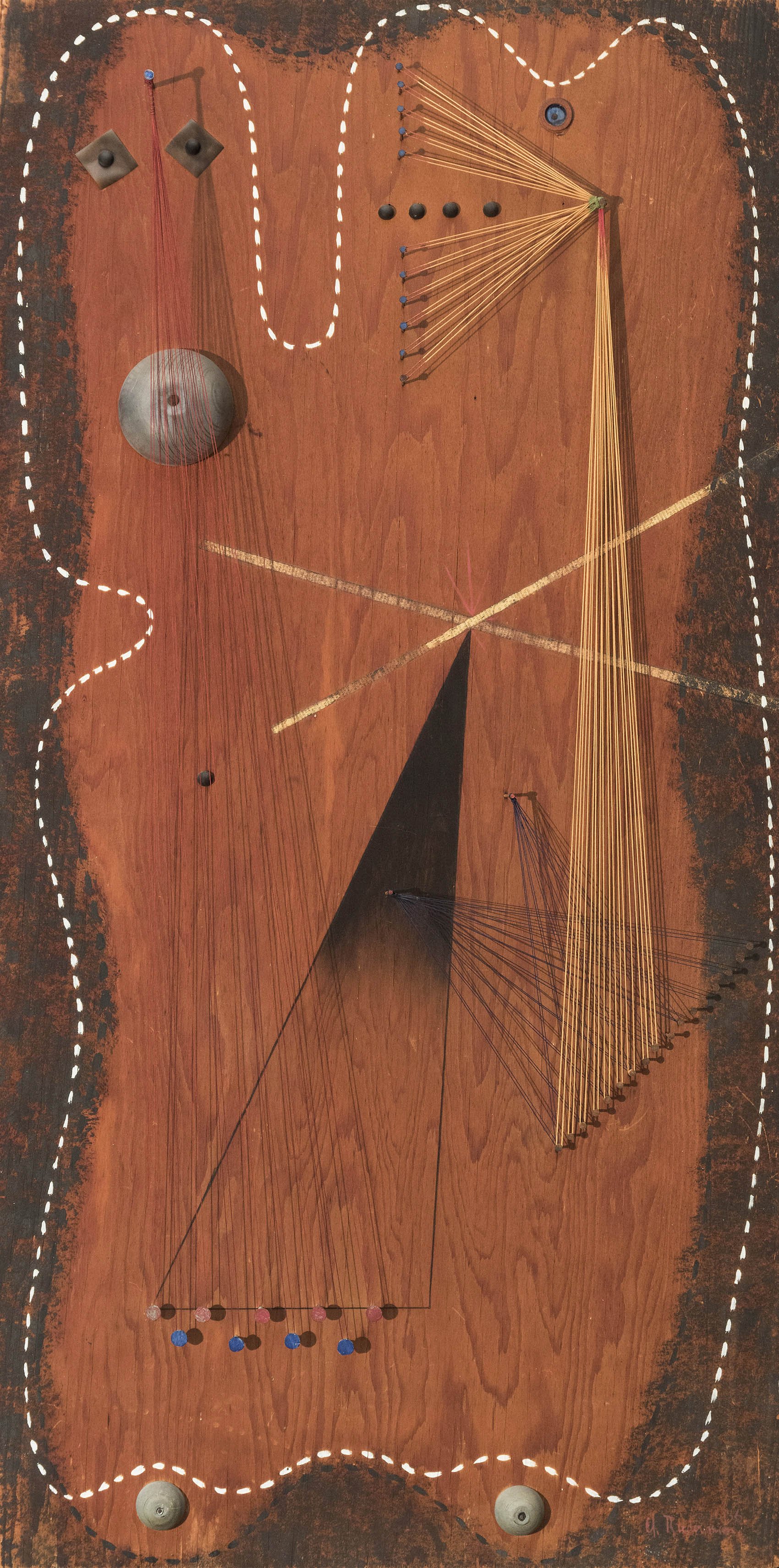

Charles Biederman (1906-2004) created his first reliefs and collages in 1935. Biederman wrote in his influential 1948 book, Art as the Evolution of Visual Knowledge, that 20th century artists were challenged to keep painting relevant once photography freed art from its pictorial task. This placed importance on the structure of a composition leading many painters to be more sculptural in their thinking. Biederman encouraged artists to seek out manufactured materials to create new art that would not mimic nature. In his earliest constructions, Biederman made sculptural wall reliefs, using wood, metal, nails, and string as seen in R-2, New York, 1936. While in Paris from October 1936 to June 1937, Biederman was struck by the technology displayed at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair. This moved Biederman towards a stricter use of pure geometry and new materials, including Plexiglass.

Gertrude Greene (1904-1956) made her first wood constructions in 1935 based on collage studies. Her early constructions reflected a dual interest in biomorphic and geometric abstraction. By 1940, Greene’s work aligned with Constructivism, with cleaner forms and simpler geometry as seen in the collage 39x1, 1939. While working in three-dimensions, Greene still used pictorial depth techniques in her constructions. For example, in 39x1 Greene placed a black piece of paper slightly over a similarly shaped larger white piece, an overlapping tool used to imply projection.

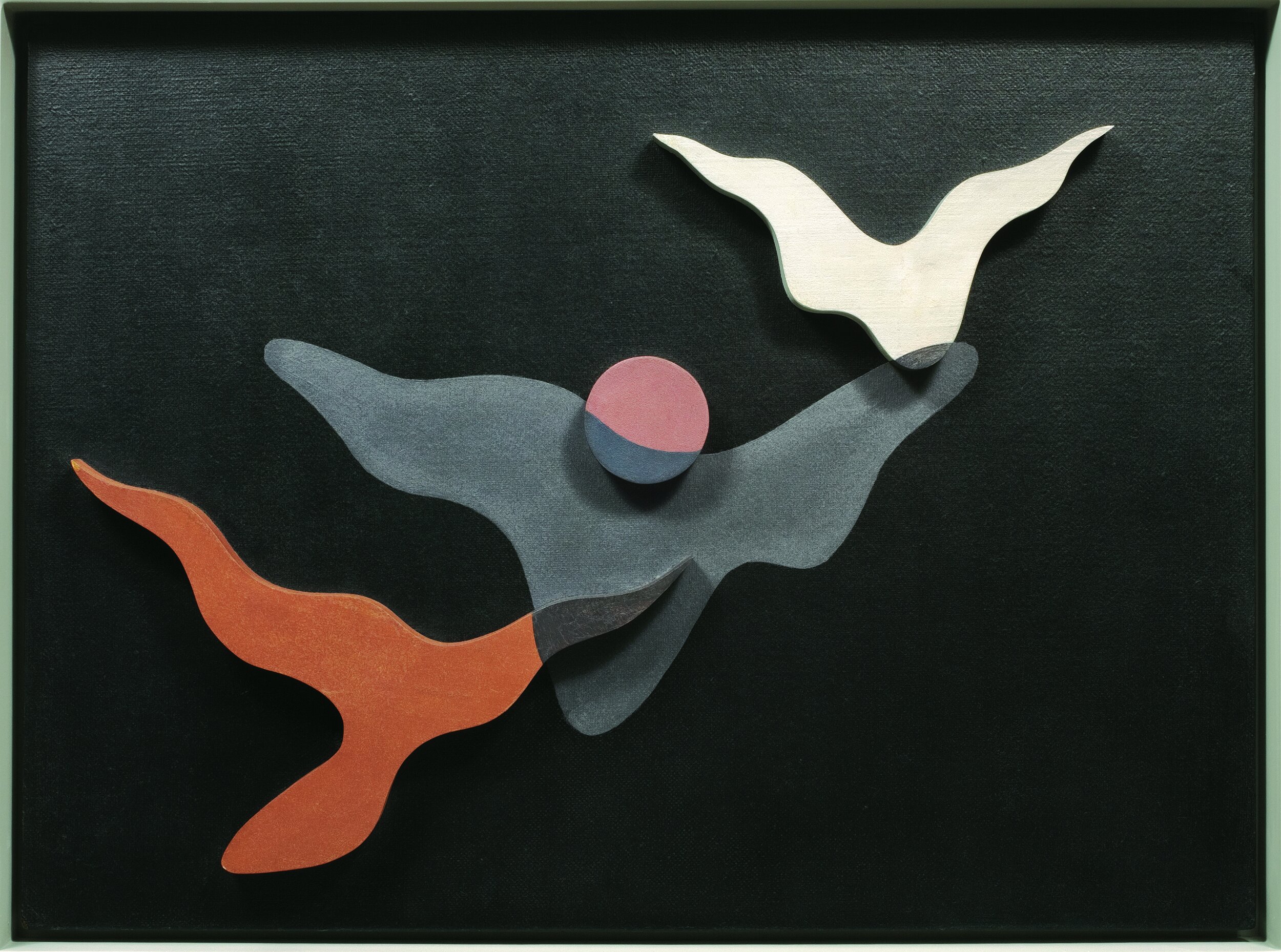

Charles Green Shaw (1892-1974) created one of his first constructions Day and Night Polygon in 1936 by cutting a wood panel into a multi-sided shape and adding wood elements to give it physical dimension. In a 1938 article for the magazine Plastique (edited by Jean Arp, Shaw, and others), Shaw defined his Plastic Polygon as “a several-sided figure divided into a broken pattern of rectangles.” Shaw also worked with biomorphic forms screwed onto a square or rectangle backboard, which he called Reliefs. The process of composing a relief mirrored collage as Shaw prepared his wooden forms first then arranged them on a board, as in Sky Float, 1938 in our exhibition. Shaw exhibited 26 constructions (Polygons, Reliefs, and Cut-Outs) at his New York dealer Valentine Dudensing in the spring of 1938. The exhibition included one of Shaw’s most irregular shapes, Day Break, 1938, in which a white polygon is activated by a small yellow circle within it.

Irene Rice Pereira (1902-1971), known for her layered glass constructions, used a trapezoid shape for the 1943 symbolic Self-Portrait she exhibited at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century. The shape conveys a deep space receding into the distance. Pereira added to this spatial effect by foreshortening the two figures in the work to imply they soar above the viewer. In Self-Portrait, Pereira broke with the traditional canvas shape to heighten the impact of her narrative statement.

In the 1960s paintings and constructions combine for a new form- the shaped canvas

While enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Architecture from 1953 to 1956, Sven Lukin (b.1934) attended lectures by the influential architect and urban designer Louis I. Kahn. Kahn’s celebration of monumental scale, unadorned surfaces, and volumetric forms inspired Lukin’s artmaking, leading him to be one of the first Americans to explore the shaped canvas. His earliest shaped paintings from 1961-62 were built up from three to five connected canvases. Next he worked with a single canvas with raised edges or center to create a concave or convex shape. Examples of Lukin’s single canvas shapes include Untitled, 1963 in our exhibition and Dwan Song exhibited at the Dwan Gallery in Los Angeles in 1963. In both, a symmetrical arrangement of one repeated shape is centered on an elevated structural support. These paintings are the most classical and restrained Lukin would create. Lukin broke with symmetry and moved into organic forms, creating eccentric shaped canvases from 1964 on. Flaunting his ability to both think and build three-dimensionally, Lukin pushed the shaped canvas into a nearly 120 foot long installation made for the Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Plaza Art Collection in Albany in 1969.

In the group show Seven New Artists at the Sidney Janis Gallery in 1964, Charles Hinman (b.1932) exhibited flat canvases balanced in suspension by cords and a few shaped canvases with physical depth, like Poltergeist, 1964, purchased by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). In Hinman’s volumetric shaped canvases, he explores the fusion of sculpture’s real space and painting’s illusionary space. Hinman’s bright colors and automobile-like curves give a Pop aesthetic to his 1960s paintings, perhaps an influence of his first studio mate James Rosenquist. The biomorphic shape of Untitled, 1965 suggests a landmass and the stripes of color act like topographical markings with a central ridge of vibrant yellow accentuating the physical depth of the piece. Untitled, 1965 was purchased out of Hinman’s 1965 exhibition at Feigen Gallery by Alfred Barr of MoMA. While artist-in-residence at the Aspen Institute the summer of 1965, Hinman produced about a dozen small paintings, including our Orange Sunspot, 1965. Hinman explored the inflection of a curve in the Sunspot series and exhibited them at Richard Feigen Gallery in January of 1966.

Neil Williams (1934-1988) is the only artist in our exhibition included in the two shaped canvas exhibitions of 1964-1965. Raised in Utah and Colorado, Williams credited exposure to the art of Navajo and Plains tribes for the order and balance in his work. Williams’s first solo exhibition at Green Gallery in May 1964 was followed by solo exhibitions at Dwan Gallery (1966) and Andre Emmerich Gallery (1968). In the early 1960s, Williams filled his canvases with parallelograms and in 1964 jutted out the canvas edge to recall the shapes within. Next in his 1964 Transparency series, the external shape was determined by the sliding and rotating of overlapping forms. Untitled, c. 1964 is a transitional work between the parallelograms and the Transparency series. Williams continued to work in shaped canvases until 1973, though they were no longer Hard-Edge after 1968. Williams shared a studio in the Hamptons with Frank Stella in the 1970s when both artists moved to collage-like painting.

Alexander Liberman (1912-1999) was raised in Paris by his Russian parents. He designed stage sets in Paris in the 1930s and worked at Vu, the first magazine to illustrate the news with photographs. Liberman arrived in New York in 1941 where he found a job at Vogue. The circle was the subject of Liberman’s first solo exhibition held at Betty Parsons Gallery in 1960, which included one tondo and one collage. The tondo Omicron V, 1961 was one of three tondos in Liberman’s 1962 exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery. It is a classic example of Liberman’s reductive approach of arranging a few elements in a flat, open field to produce an optical afterimage. This led to his inclusion in MoMA’s The Responsive Eye, an exhibition which presented the international Op Art movement in 1965.

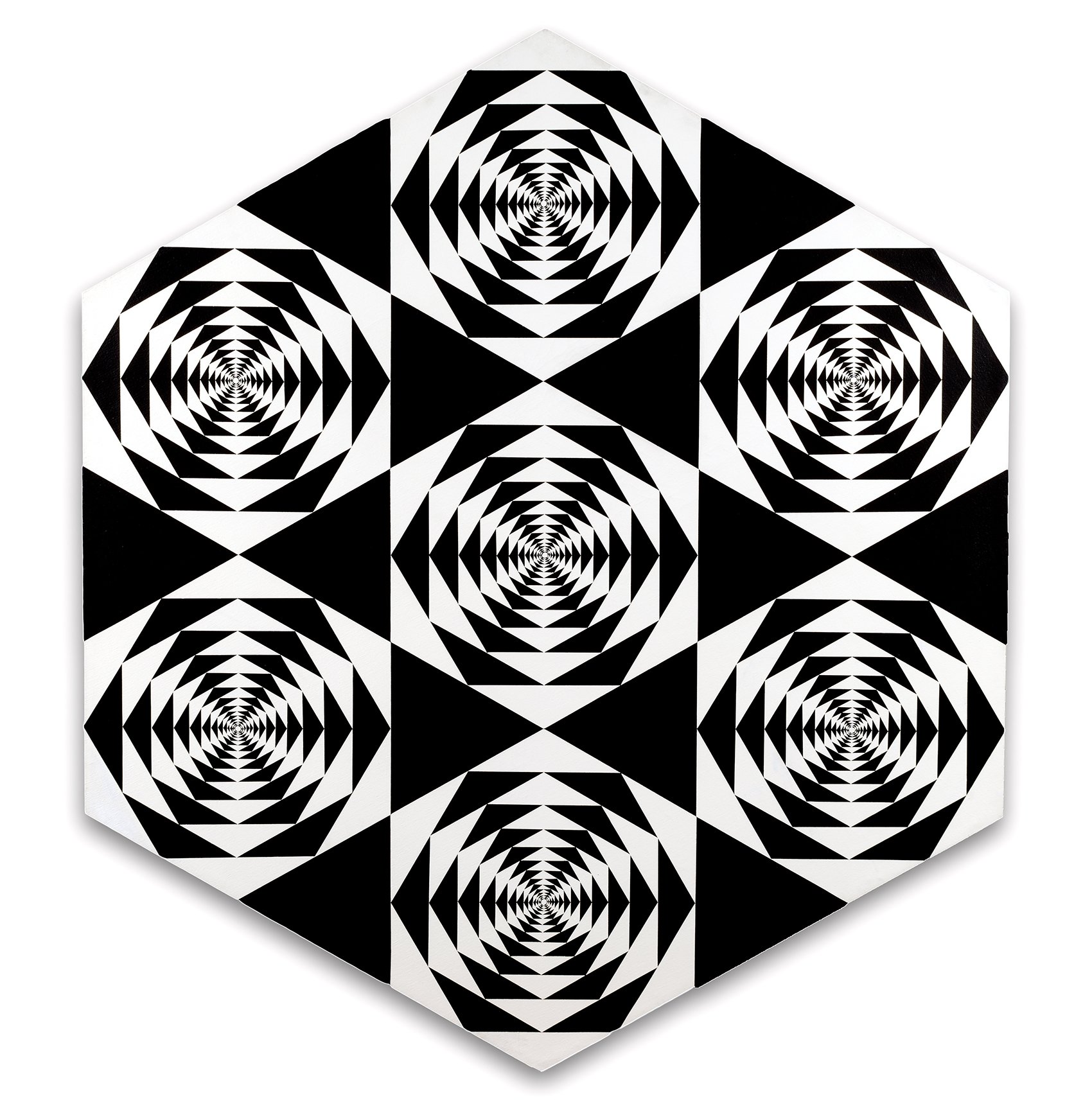

From 1965 to 1968, Francis Celentano (1928-2016) worked in shaped canvases and motor-rotated tondos. Celentano created studies for his complex arrangements by screenprinting triangles into patterns he collaged into larger arrangements to test the optical effect. Celentano achieved national recognition with his inclusion in MoMA’s The Responsive Eye. In Seven Hexagons, 1965, Celentano chose a form for his shaped canvas that is repeated multiple times within it. The high contrast of black and white in each hexagon creates an afterimage of a yellow hexagon pulsing along the outer ring of hexagons. The afterimage reflects the canvas shape and contents, taking to new heights Frank Stella’s concept of the outer bounds of a painting being defined by its internal composition.

In 1965 Thomas Downing (1928-1985) first applied his grids of colorful dots to parallelogram canva--ses. Like other members of the Washington Color School, Downing’s work engaged the raw canvas as an active component of a painting, so it was not a stretch for Downing to consider the canvas shape as another choice in his creative process. Downing’s first shape was the parallelogram which pushed his dot motif into a thrusting forward movement. One of Downing’s parallelograms was included in Lawrence Alloway’s Systemic Painting at the Guggenheim in 1966. The parallelogram in our exhibition Untitled (Variations of Red), 1966, has subtle color variations in the dots, activating the whole. Downing next did shaped canvases of parallel stripes with one or two bends, which were exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery of Art (December 1966 - January 1967). The catalogue for the exhibition illustrates that these stripe paintings could be hung in multiple orientations on the wall. In 1967, Downing used isometric perspective in the Plank series to give the appearance of separate canvases projecting from the wall in three, five, or seven units. In the Fold series of 1968, Downing chose a form that implies a folding canvas in multiple colors. In the Plank and the Fold paintings, Downing stretched one canvas over a single board of shaped plywood to achieve his effect. In Fold One, 1968, the colors - two shades of green, pink, and blue- do not adhere to color theory concepts of projecting and receding color. Instead while the Fold shape strongly suggests a three-dimensional form, the colors counter the structure, giving the work the impression of a gravity-defying form folding in space.

Paul Reed (1919-2015) considered the overall form of a painting in 1966 by drawing out shapes to see how color could work without a clear central axis. By twisting and pulling his grid to a peak, Reed created a five-sided shaped canvas he called Topeka. Intrigued by the effect of color pushing beyond the constraints of the canvas, Reed worked in increasingly complex shaped canvases from 1967 to 1970, in which he pushed the dynamic relationship between inner structure and outer shape. To begin a series, Reed first mapped out the shape on grid paper to determine the volume and estimate the interpretation of depth. He then worked in collage to determine what colors would reinforce that reading. Settled on a shape, he made a series of canvases with different color arrangements to push the complexity of the color interaction. The series Marmara (a sea in Turkey) and Safid (a river in Afghanistan) have a centered depth that referenced looking through Islamic architecture to sources of water. Reed used color to indicate planes and create depth with matte and fluorescent paints. Marmara, 1968 has an open blue center with each edge sculpted in a vibrant color. In Safid, 1968, the choice of bright green for the center aided by planes of deep blue increases the isometric projection.

Ralph Iwamoto (1927-2013) came to New York in 1948 on the GI Bill to spend two years studying at the Art Students League. Raised in Hawaii by a family of Japanese heritage, Iwamoto served in the US Army from 1946 to 1948 as a translator in Japan. Iwamoto first worked in organic forms, muted colors, and elements from traditional Japanese art, which led to his inclusion in two Whitney annuals (1958 and 1959). Iwamoto worked as a guard at MoMA from 1957 into the early 1960s, where he befriended fellow guards Dan Flavin, Robert Ryman, and Sol LeWitt. He worked on some of Sol LeWitt’s early wall drawings and remained close friends with the group. Iwamoto’s work became more geometric in the 1960s. He did a series of shaped canvases from 1966 to 1968, in which the canvas edge is activated by arrangements of right-angled lines that move the viewer’s eye around the boundaries of the shaped canvas. He continued the lines around the canvas edge, adding to the sense that his work was both painting and object. In Melpomene, 1967, an ochre center holds the painting as the three sections of pale lines seem captured in a moment, about to unfurl and re-arrange their positions. Iwamoto had two exhibitions of these paintings, first at Watson Art Gallery at Elmira College in 1968 and then at Westbeth Gallery in 1973.

Theo Hios (1908-1998) came to New York in 1934 from Greece. He enrolled in WPA art classes and began exhibiting with the Artists’ Union in 1936. He served as a combat photographer with the Marines in the Pacific during World War II and used the GI Bill to study at the Art Students League. In New York, he was part of an expat group of Greek artists, including Nassos Daphnis and Michael Lekakis. In the 1960s, he found his own style with bold ellipses of overlapping color, suggestive of collage with their flat color and defined edges. The circular shape of his compositions left him wondering how to treat the corners of his painting. By 1967 Hios eliminated the corners, increasing the impact of his ellipses, which bulge and move in Tondo, 1968. He playfully titled his ellipses paintings The Apollo Series, referencing both Greek myths and the excitement of American space travel. Hios had a home and studio in Hampton Bays and had two solo exhibitions at the Parrish Art Museum in 1964 and 1972.

Al Loving (1935-2005) studied painting at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. In 1968, he relocated to New York and the following year became the first African-American to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Loving used a hexagonal canvas to create three-dimensional renderings of geometric shapes. He took Josef Albers’ nested squares and turned them into crystalline cubes, playing with the tension between flatness and spatial illusionism. Loving added complexity in his Septehedron paintings by opening one side of his cube into an arrangement of four triangles. In Septehedron L-B-4, 1970, three-dimensions are conveyed through crisp outlining of each triangle in pink, blue, and green. In the Cubes and Septehedrons, Loving used traditional perspective devices as a way to juxtapose and play with color. In the 1970s, Loving shifted to torn canvas and collaged paper works, combining pieces of cut and torn canvas or paper into overlapping colorful patterns and shapes. Loving’s 1960s work and 1970s work look strikingly different, yet in both the shaped work is oriented on the wall, embracing the tradition of painting while challenging its definition.

[ TOP ]

Modernism 1913-1950 | Realism of the 1930s and 1940s | Abstraction of the 1930s and 1940s | Post-War | Selected Biographies