May 23rd - September 8th, 2023

Installation Views | Essay | For availability and pricing, call 212-581-1657.

Installation Views

The Bertha Schaefer Gallery gave Charles Green Shaw 6 solo exhibitions from 1963 to 1973. Each catalogue listed 22 to 30 large works with a note that smaller paintings were available. As a founding member, Shaw continued to exhibit with the American Abstract Artists and the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors in the 1960s. Shaw was included in the Whitney Museum’s 1962 traveling exhibition Geometric Abstraction in America.

Shaw’s work is in over 50 museums. His 1960s works are in the following collections: Brooklyn Museum, Joslyn Museum of Art, Sheldon Museum of Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Telfair Museums, Ulrich Museum of Art, and Yale University Art Gallery. In addition to art, Shaw had 4 books of poetry published from 1959 to 1969.

Essay by Emily Lenz

Charles Green Shaw (1892-1974) had his first exhibition in New York in 1934 (Manhattan Patterns at Valentine Dudensing Gallery) and his last in 1973 at Bertha Schaefer Gallery. For four decades, Shaw had solo exhibitions with top New York galleries and while styles came in and out of fashion he continued to work in abstraction. Our exhibition presents works from his years with Bertha Schaefer Gallery, 1963-1973. In the six solo exhibitions there, Shaw exhibited the largest canvases he ever executed, an impressive feat for a man in his seventies. In the 1960s there was finally an appreciation and market for the hard-edge style Shaw first used in the 1930s.

In joining Bertha Schaefer Gallery in 1962, Shaw connected with another generation of young artists, such as Will Barnet. Shaw had close relationships with each of his art dealers and often accompanied Schaefer to openings and parties. Shaw frequently dropped in on his first dealer Valentine Dudensing in the 1930s to see the great Europeans he handled such as Picasso, Miro, and Mondrian. The Dudensings and Shaw socialized in New York and Paris and when war broke out in Europe the Dudensings took Shaw to Bermuda in 1941. When the Dudensings retired to France in 1947, Shaw showed with Georgette Passedoit until her retirement in 1960. Bertha Schaefer visited Shaw in 1962 and gave him his first exhibition in January 1963. In the 1930s, faced with few sales due to the Depression and a small audience for American abstraction, Shaw made only a few 40 x 30 canvases each year, preferring 16 x 20 works on canvasboard he could easily store. He increased the number slightly in the 1940s as the early Guggenheim Museum and the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors created exhibition opportunities. Schaefer’s gallery had room to exhibit 20 large scale works each exhibition and Shaw enjoyed having a market for large works.

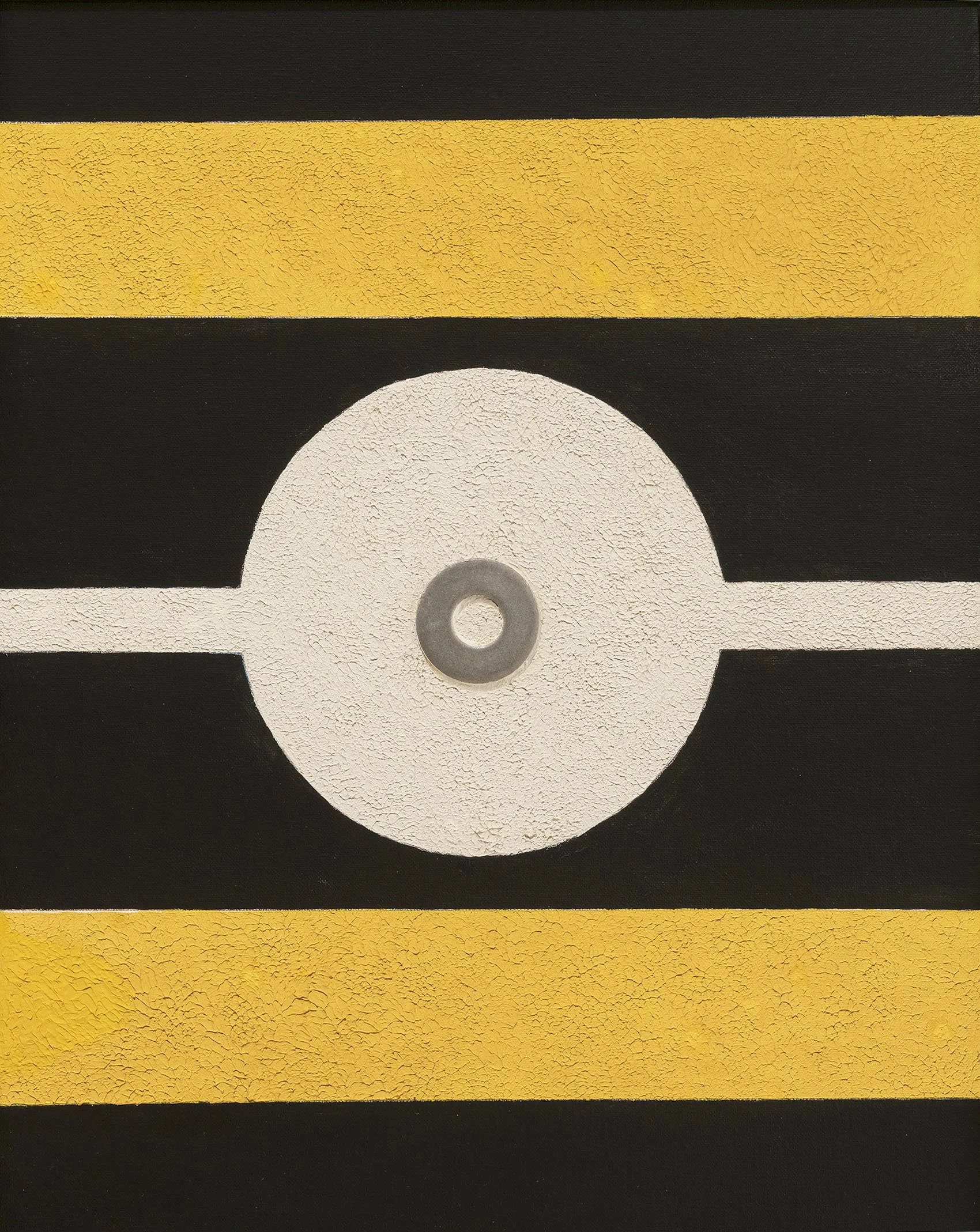

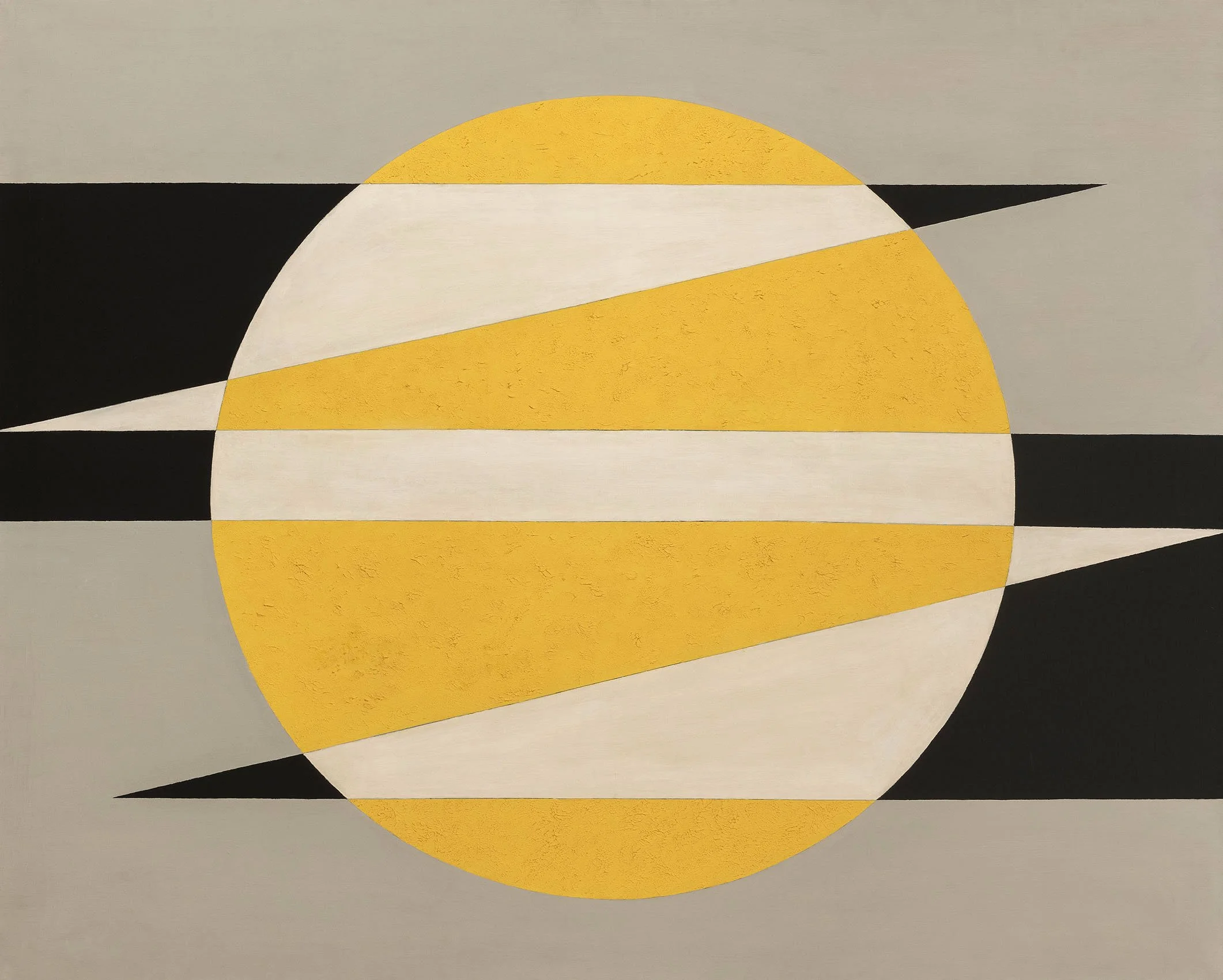

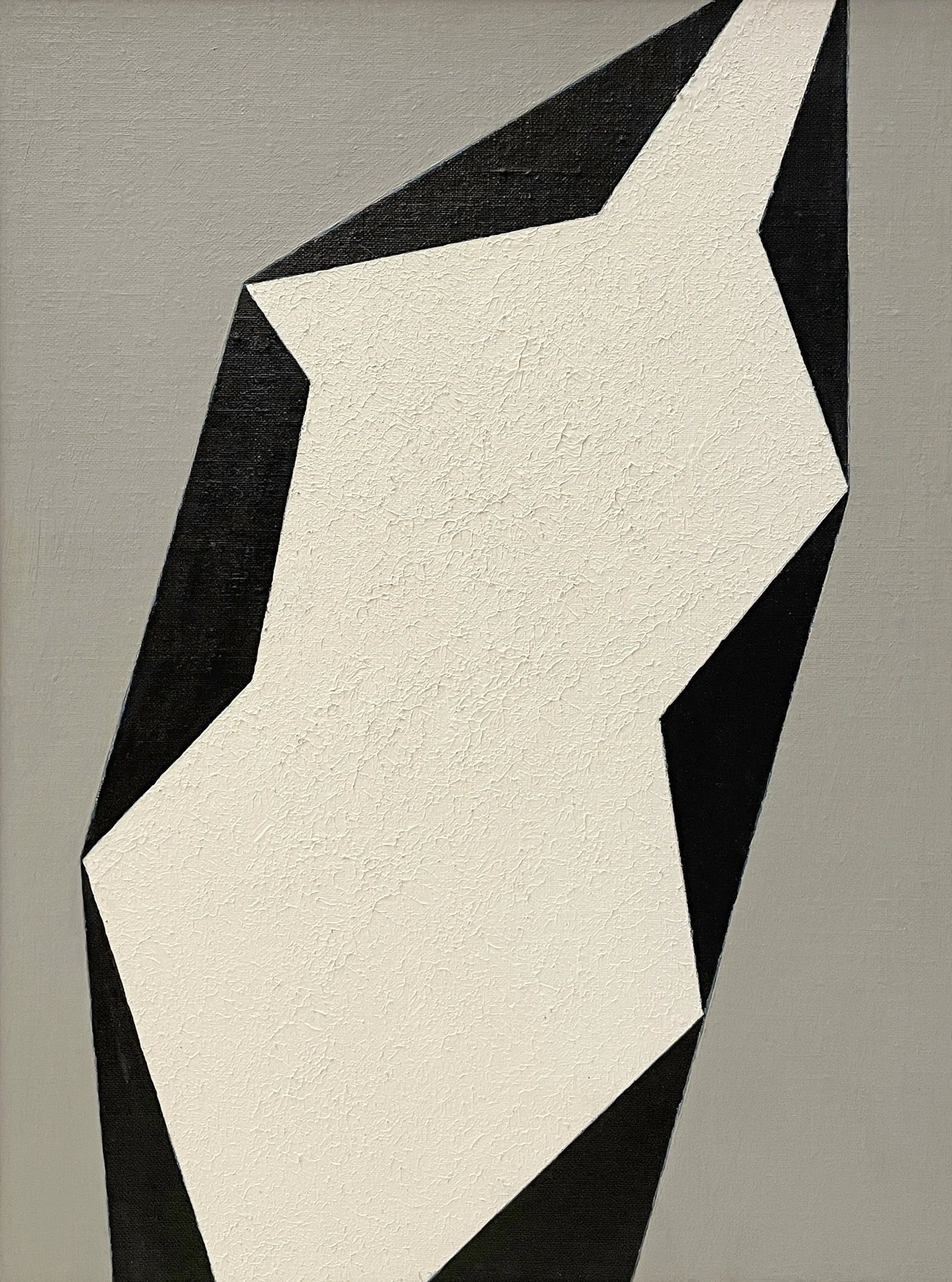

Admiring the work of Ellsworth Kelly (1923-2015) and Frank Stella (b. 1936), Shaw pared down his geometric compositions to polygons, circles, and lines in the 1960s. He aimed for the works to have solidity and impact, as well as balance while simplifying the shapes. Yet Shaw’s canvases differ from the 1960s hard-edge style in their painterliness. While artists like Kelly and Stella were erasing the artist’s hand in their flat paintings, Shaw built up texture in large areas of his canvas. This stippled texture first appeared in Shaw’s 1930s compositions as a nod to Cubism. The texture in the 1960s works adds dimension and draws the viewer in while the large forms powerfully push out. Shaw has a limited palette during this time of green, red, and yellow along with black and white. Yet variation in hue is achieved through underlayers of another color, often blue. Shaw discovered in taping out his shapes that he could allow the underpaint to show just slightly along the edges of the shapes. These nearly imperceptible borders give the compositions vibrancy and tension in the balance of large shapes. While the works first appear minimalist, the added texture and colorful outline makes the paintings dynamic.

In the press release for Shaw’s first Bertha Schaefer exhibition, he said:

In all I have sought the cadence of color and curve of movement, combining an organized rhythm with the impact of mass and pull. In none of them has purpose yielded to chance nor has accident played a major role. This work is not the result of a year or two of painting, during which period it was conceived, but rather of some thirty years’ trial and experimentation, whose empirical efforts have culminated in these canvases.

Shaw was most productive in generating ideas in the summer. Starting in 1944, Shaw spent much of the summer on Nantucket, sketching and writing poetry at the beach. He drew in pencil, refining the proportions of a shape over many sketches, going through three 30-page sketchbooks a month. Settling on a shape, he would make a watercolor or tempera study on a 9 x 12 inch sketch pad. Back in New York in the fall Shaw reviewed the tempera sketches, which he called documents, with friends and his dealers Passedoit and Schaefer to select compositions to execute in oil. First Shaw would paint a 12 x 16 inch canvas based off a sketch then select the best to build up into exhibition-size canvases. Shaw’s methodical process created large scale paintings that are assured and bold with meticulous straight edges and varying textures.

At the height of the Space Race in the 1960s, Shaw explored flight and space with openings and voids within amorphous shapes. In the Silhouette paintings, the central image appears both sculptural and as an opening. Exploring optics and perception, Shaw created compositions that draw the viewer in or push out into the viewer’s space, as seen in the bisected black circle in Breakthrough. Shaw’s highly calculated and refined composition use the push-pull of postwar painting to create a balance of tension and solidity in his dynamic works that engage the viewer.