September 14 - November 10, 2023

Installation Views | Essay | For availability and pricing, call 212-581-1657.

Installation Views

Essay by Deedee Wigmore

There is a relationship between style and societal dynamics, as seen in the variety of art made by American artists in the 1930s. In the past American art had been adaptive of the styles developed by artists in other countries. Art was a luxury for the few and like all luxuries in a depression, art suffered. Art served a national function in the 1930s and was fused into a product with an American identity. To serve this cultural purpose in a decade of social and aesthetic changes, mainstream American art was realistic and its representations of familiar scenes in American life effectively functioned to validate the country’s nationalistic spirit. The Stock Market Crash of 1929 ended the prosperity of the 1920s. Industrial development declined steadily, mortgages were foreclosed and the dispossessed could be seen camped out or on the road looking for work. The problem of relief was passed onto the states and private charity.

William Gropper, The Last Cow, 1937

The enactment of a multi-phased six-month program of New Deal relief for the arts began in 1933 with the Public Works of Art Project. It supplied work for unemployed qualified artists in decorating non-Federal public buildings. In 1934 a second program, the Section of Painting and Sculpture of the Treasury Department, began and continued through 1943. This second program provided relief by employing artists to produce murals and sculptures for existing Federal Buildings. It was more than a relief program, it became a cultural one with regional competitions and centers for creating, exhibiting, teaching, and recording art under Holger Cahill. This program broke the narrow boundaries of connoisseurship and created a national reservoir of art appreciation. Rigid control of style and subject matter were not conditions for this relief. These government employment programs made the artists feel needed to paint what the Depression meant to America. Their art said, “This is my country” and it was called art of The American Scene. It expressed in the descriptive language of representational realism a firm belief that it was the social responsibility of the artist to communicate through a language understandable to the public. The American Scene was made up of different groups of realists: Regionalists, Social Realists, and Modernists, an umbrella term for art that retained elements inspired by older styles such as Precisionists, Magic Realists, and folk art. This sanctioned diversity of styles operating within realism allowed artists to appropriate ideas and fuse them into something new with an American identity, key to the dynamism that allows us to move forward so creatively.

Clyde Singer, Jim, 1936

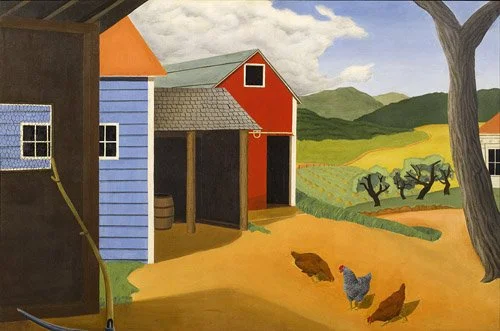

The largest group of representational artists were the Regionalists. They painted rural American scenes that glorified the simple mode of life lived in a community close to the soil. Their paintings reflected a desire to rediscover the history and regional achievements of each state. Urban realists could be counted as Regionalists when their keen observation of urban living expressed an appreciation of the opportunities city life provided.

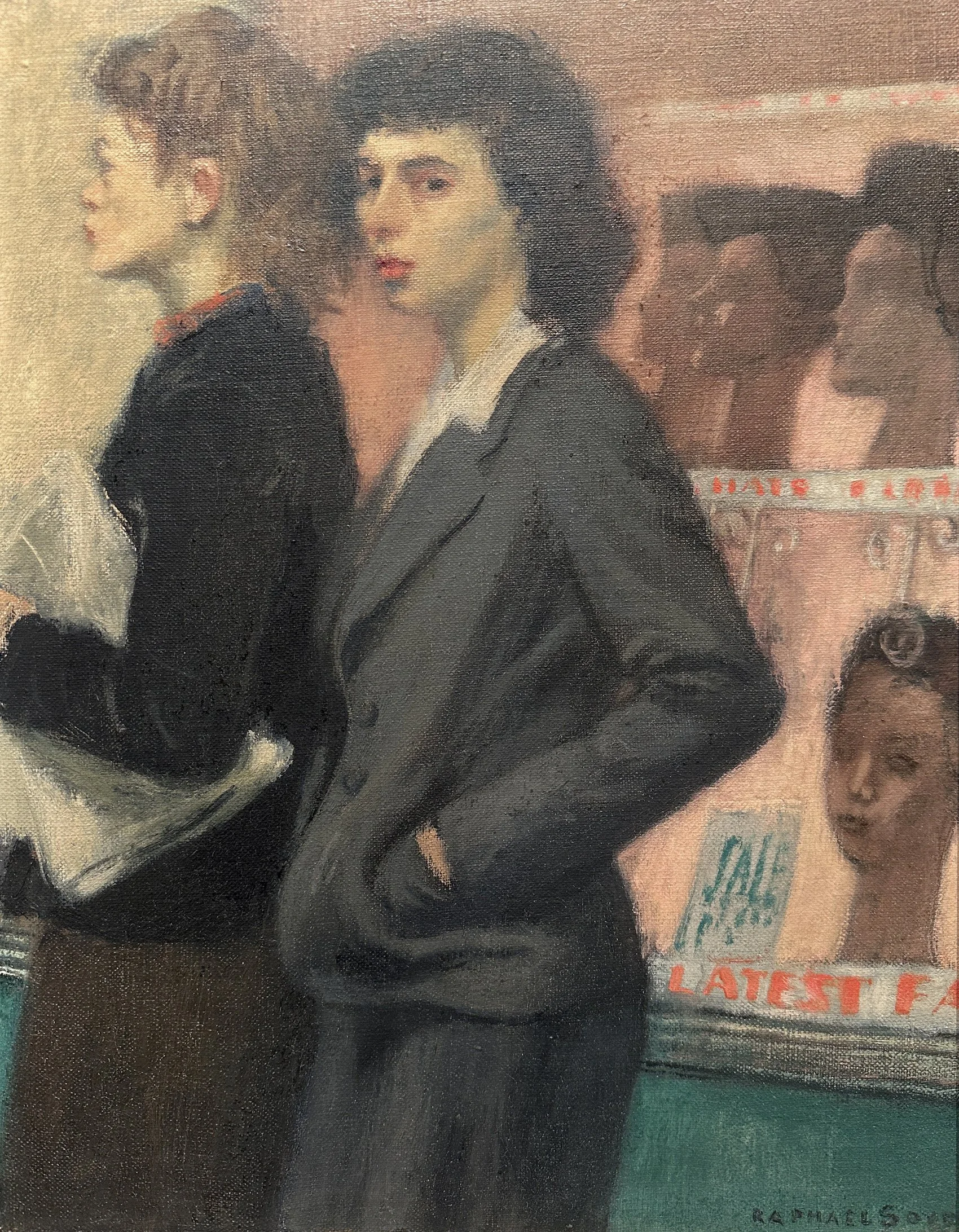

Raphael Soyer, Men at the Mission, 1935

Another group called the Social Realists focused their art on appeals for economic equality. This group were often immigrants striving to succeed in America and become a part of the mainstream. Class consciousness was replacing ethnic consciousness for some in this group. Anger against the idealized majority culture was expressed in their art. The art of social protest was as much a part of the American Scene as Regionalism. Its realism differed in subject matter and attitude. The Social Realists painted unemployment, strikes, and lynching subjects. Depending on the subject, a painting’s mood was expressed in color selection, such as somber colors to suggest sadness and resignation or bright strong colors to indicate action and sound. The Social Realists could also surprise you with a positive statement about the history, habits, or environment they felt should be noted.

Allan Gould, American Farm, 1930

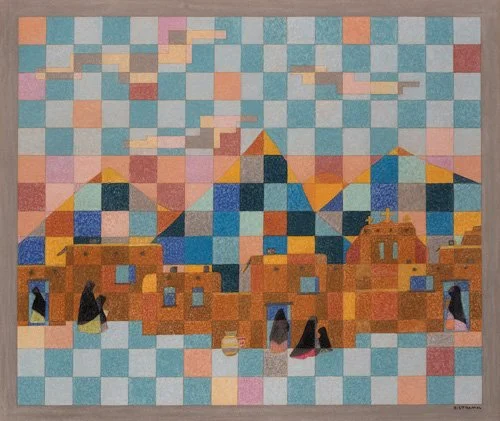

Emil Bisttram, Adobe Village, 1936

Modernism continued to evolve in the 1930s even though it was pushed out of the mainstream as the country turned away from Europe, not just its art style but its problems of war and revolutionary ideology. American Nationalism in the 1930s was focused inward on building and rediscovering what was American. Folk art was praised as a symbol of American self-sufficiency. It was a product of a time when the artist-craftsman was linked to his local community through the production of artful objects available to all. The rediscovery of American folk art paintings attracted Modernists who began to collect it and found its direct simplicity influenced their style. The Modernists did not forget conceptual tenants of art absorbed and transmitted by Americans visiting or studying in Europe before 1930; their knowledge continued to be taught, evolve, and be transformed into American statements. New York’s Museum of Modern Art, founded in 1929, continued exhibitions focused on diverse sources of Modernism throughout the 1930s including American folk art, Abstraction and Surrealism. American Modernist artists felt that socially relevant art could be made without using art as propaganda.

The Modernists argued Abstraction and Surrealism allowed for the discovery of new possibilities which would create a renewed dynamic America. Modernists combined an American subject executed realistically with their interest in aesthetic dimensions - texture, form, color, and organization. The Transcendental Painting Group, a loose organization of New Mexico artists, explored the projection of spiritual and imaginative qualities into art with an emphasis on the formal and emotional elements rather than the subject matter. Another group that evolved out of European Surrealism in the 1930s were the Magic Realists. They created a dream-like world to bring to the surface internalized experiences. Depictions of familiar objects in new spaces, forms, and relationships were used to comment on or question reality. Pure Abstraction was not a part of the American Scene movement, but was a growing force during the 1930s. So, it is not surprising that elements of abstraction were incorporated into realistic works by some of the American Scene artists.

At the close of the 1930s, these artists working in different styles of realism as part of the American Scene movement were exhibited together in the 1939 New York World’s Fair to reflect the American democratic spirit. Our exhibition of art styles in the 1930s includes mural studies, paintings, and sculpture by Regionalists, Social Realists, and Modernists handling topics of employment, immigration, industry, and the varied landscape of America.